And the headline story from American Affairs Journal:Economics and Markets Commentator

Weak growth is far and away the most important economic problem facing the United States. This problem is not simply the result of the financial crisis or the severe recession that followed; the period of low growth began in 2000. Rather, it is the result of a much earlier reduction in business investment.

While short–term growth depends on demand, it is rising supply—the ability of the economy to increase output—that determines economic success over time. America’s problem is the slow growth of its potential to supply goods and services caused by two decades of underinvestment.

Although commentators have blamed this weakness on various issues, the data show that the major cause has been a change in the way company managements are paid. The 1990s saw the arrival of the bonus culture, which massively shifted management incentives and thus changed management behavior. Sadly, the change did immense damage to the economy. Managements were encouraged to invest less and, with lower investment, growth faltered.

The change in how managements were paid had immediate and profound impacts on their behavior. Before 2000, companies increased investment in response to corporate tax cuts, but afterwards, they stopped doing so.1 There are, of course, other things that affect investment, such as the invention of new technologies. But government policy can influence these outcomes, at best, only indirectly. A more straightforward, and likely more effective, policy approach would seek to restore investment and strong growth by reversing the damage done by the bonus culture.

Had the U.S. economy continued to grow as rapidly over the past dozen years as it had before, the incomes of Americans—as well as spending on schools, law enforcement, and public health—could be 20 percent higher than they are today, without any increase in tax rates or public debt. Not only would there be more prosperity and less poverty, there would also be more resources available to address other problems. Restoring growth should therefore be the major priority for the United States, and that will require higher levels of investment.

Low Investment Is the Problem

Why has U.S. economic growth been so poor since 2000? As discussed at greater length in my book Productivity and the Bonus Culture, roughly two-thirds of the slowdown in growth during this period has been due to weaker productivity, and one-third to aging. We can do nothing about aging, so boosting productivity should be the key policy objective.

Unemployment fell rapidly after the 2008 recession but has recovered, suggesting that a lack of demand, or some hangover from the financial crisis, is not the main issue. It is supply, rather than demand, that has been the problem. Output has risen slowly because the economy’s ability to increase production has deteriorated: companies have cut back on investment, preferring to spend money on acquisitions and share buybacks.

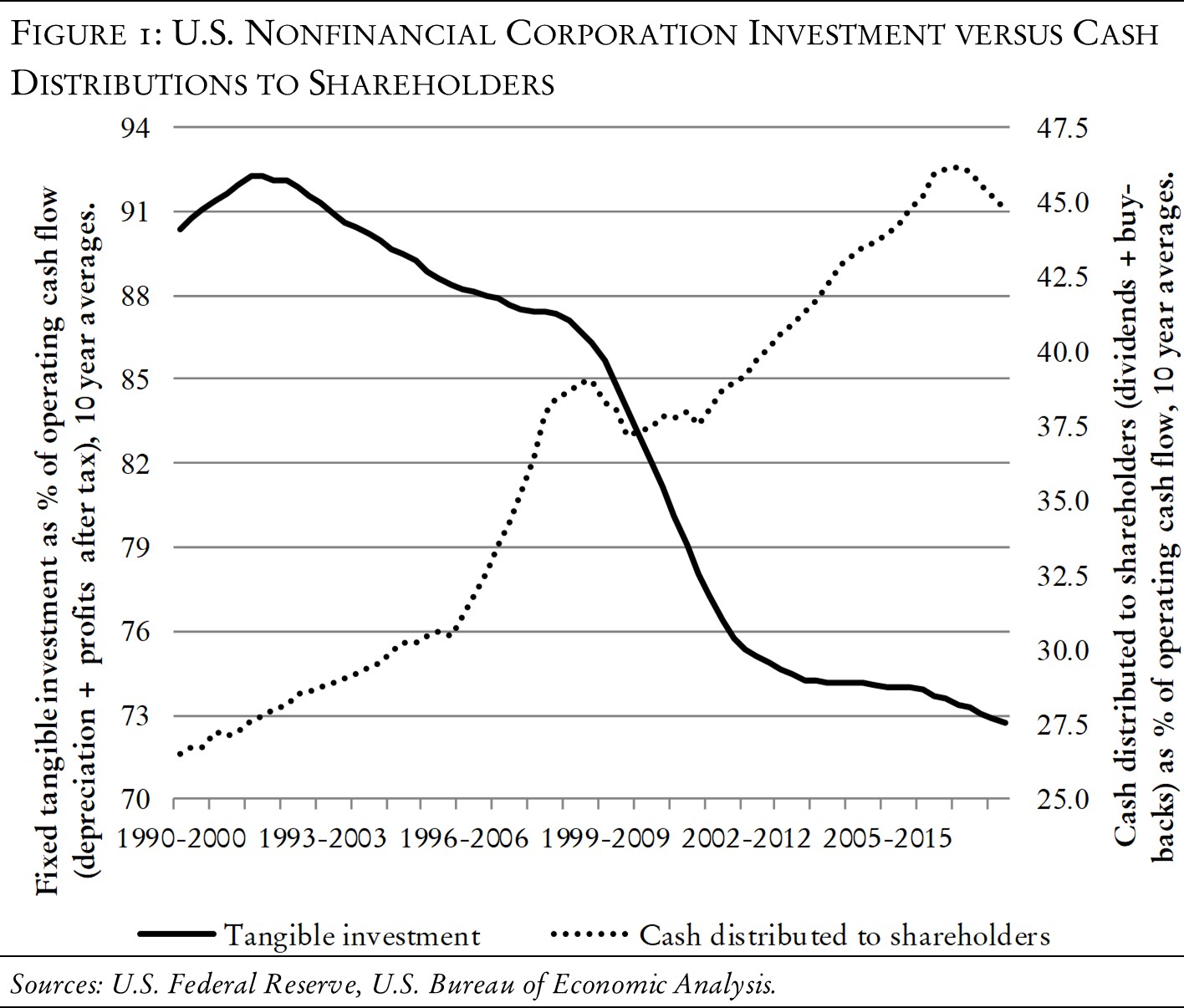

I illustrate this change in behavior in Figure 1. Investment fluctuates with the cyclical state of the economy, so I use ten-year averages for both series to iron out these blips. The chart shows a steady fall in tangible investment and a similar rise in cash payouts. Compared with the average for the decade from 1990 to 2000, investment has fallen from 90 percent of U.S. nonfinancial companies’ cash flow to 73 percent, while money distributed to shareholders via dividends and buybacks has risen from 26 percent to 45 percent.

Investment depends on two things: the rate at which technology improves and the willingness of companies to spend money on new equipment. As technology improves, there are more opportunities for profitable investment, and the extent to which these opportunities are seized depends upon their expected return. Companies seek to preserve or improve the return on their equity capital, which is the net worth of their assets after deducting their debt. When the expected return on equity for a new investment exceeds a minimum level, known as the hurdle rate, companies invest; if it falls short, they don’t. Expectations also depend partly on confidence, so the three things that determine the level of investment are changes in technology, the hurdle rate, and those swings in confidence that Keynes called the “animal spirits” of entrepreneurs.

The Cause of Low Investment Is the Bonus Culture

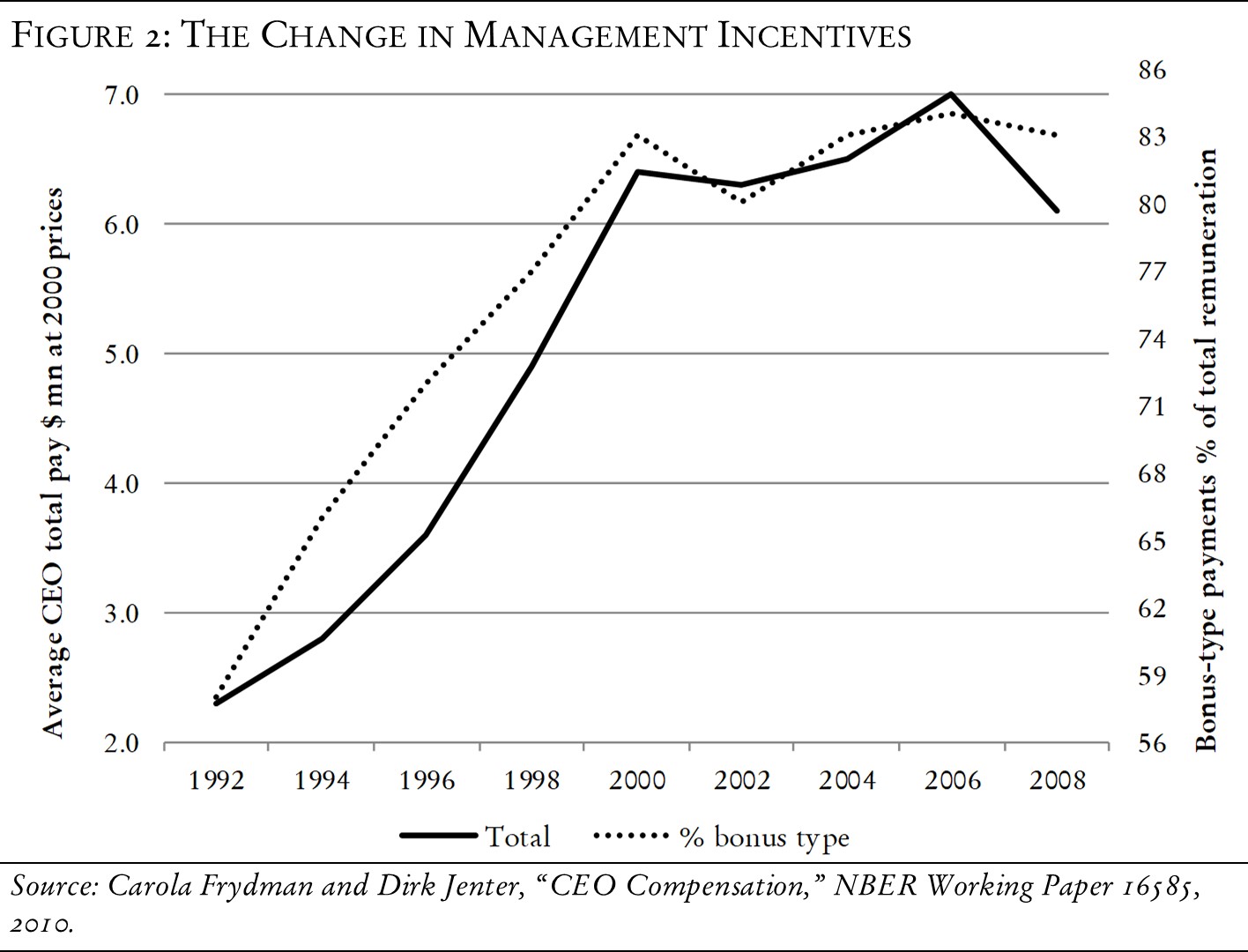

The fall in investment, and the rise in cash payouts to shareholders, followed directly after the revolution in the way senior executives were paid, which occurred in the 1990s. As I show in Figure 2, a significant change occurred in both the total compensation amount, which rose by more than three times, and in the proportion of compensation that was paid in bonus arrangements rather than as basic salary. Since the purpose of incentives is to affect behavior, we should not have been surprised—as we appear to have been—that the change in the way managements were paid altered the decisions they took. Unfortunately, the new incentives discouraged investment and damaged the economy.

With the arrival of the bonus culture in the 1990s, the changes in management compensation had the effect of raising hurdle rates, and thus caused investment to fall. Before 2000, companies would demand a lower expected return threshold on new investments than they do now. We can show that this has occurred by comparing the impact on investment of changes in corporate taxes before 2000 with the effect afterwards.....MUCH MORE

The prospective return on new investment goes up if the corporate income tax rate falls and down if it rises. We would therefore expect to see cuts in corporate taxes followed by a rise in business investment and vice versa. As Figure 3 shows, this is what happened from 1951 to 2000, but it stopped happening afterwards...

If interested after pursuing and perusing the rest of Smithers, the related ideas in 2012's "TAXES, CAPITAL AND JOBS"appear almost self-evident:

Over the last few years I've come to believe that all income, earned and unearned, should be taxed at the same rate, that preferential taxation of capital no longer leads to the intended policy effects of job creation and increasing capital investment in plant. property and equipment but rather is a bought-and-paid-for scam perpetrated by the financier class.

On a related point, it's time to get rid of the carried interest loophole which taxes income at cap gains rates for private equity and hedge funds.

That carried interest should not be treated as a capital gain can be proven quite easily.

Show me one tax return where a carried interest capital loss was allowed.

[you won't be invited to any of the meetings ever again -ed]

At the lower end of the income scale there should be some minimum tax. Everyone should have some skin in the game.

I'll be coming back to all these topics throughout 2012, in the meantime here's the granddaddy of Econ papers for folks interested in this stuff, sincere thanks to the reader who turned my vague recollection of the thesis into an actual PDF copy. It is as pertinent and fresh today as the day it was written, 34 years ago.

TAXES, CAPITAL AND JOBS

By Mason Gaffney

A paper delivered to the National Tax Association, Chicago, August, 1978.

Adapted for use in a course in Macro-economics, Winter, 1996.

By Mason Gaffney

A paper delivered to the National Tax Association, Chicago, August, 1978.

Adapted for use in a course in Macro-economics, Winter, 1996.

....MUCH MORE

Also 2019's "The Real Reason Stock Buybacks Are a Problem"

Also 2019's "The Real Reason Stock Buybacks Are a Problem"

This argument is a corollary of the fact that the preferential taxation of capital does not seem to deliver on the policy goals with which it is rationalized.

More on that after the jump.

(I'm going to get kicked out of the club aren't I?)

From the econ bomb-throwers at Evonomics:

Buybacks are a massive tax dodge for shareholders....