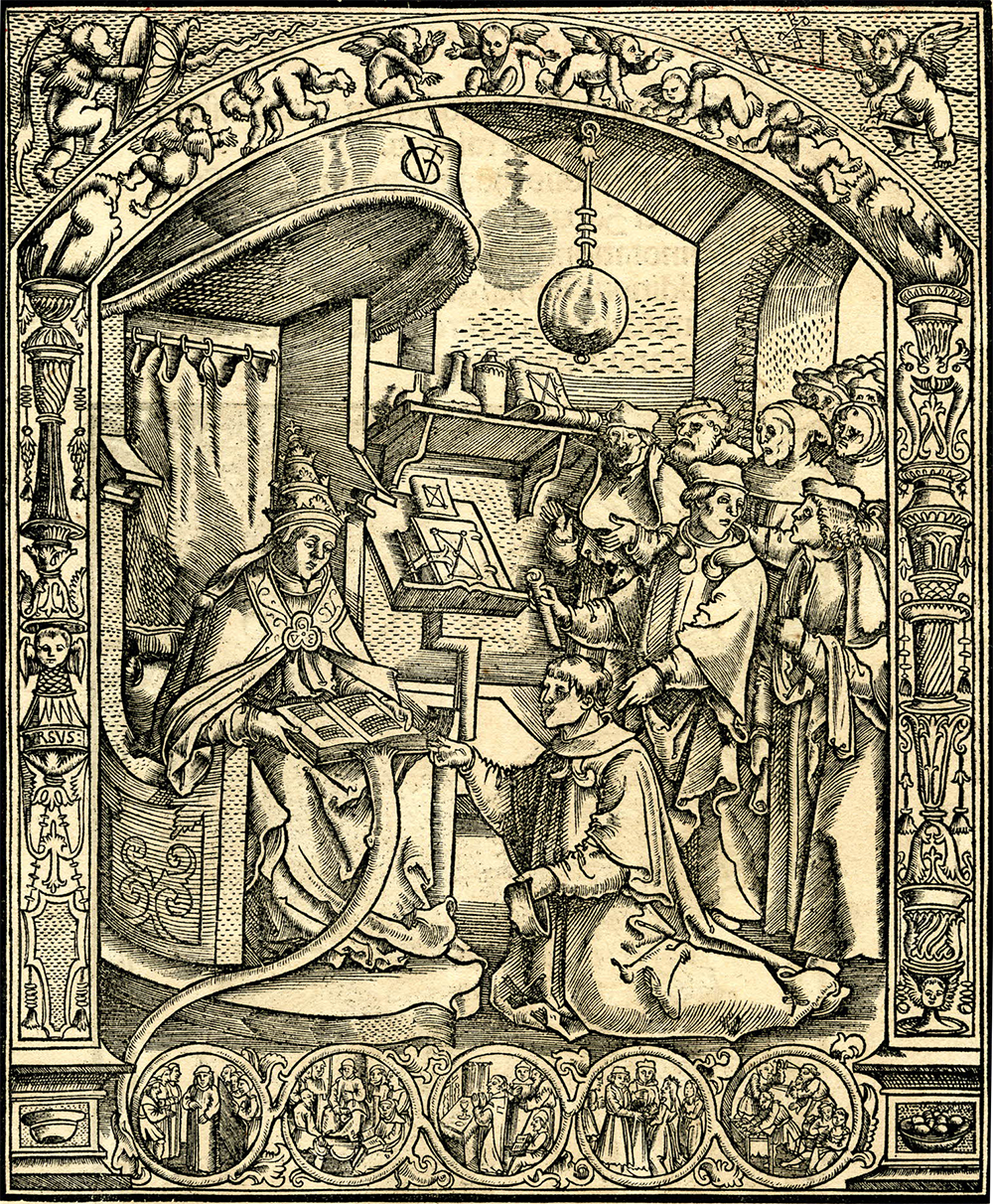

Papal Indulgences

Sur le Pont d’AvignonBeautifully sited on the Rhône River, about fifty miles inland from the Mediterranean Sea, the town of Avignon is undoubtedly one of the most alluring locales in Provence. Underneath the towering Gothic heights of the fourteenth-century papal palace, its charming streets and squares are lined with small boutiques and cafés thrown open to the sun. Les Halles, the central food market, brims with olives, fresh herbs and spices, oysters, and an enormous variety of local cheeses, meats, and breads. In the surrounding countryside, the Côtes du Rhône wine region produces some of the finest varieties in France.

On y danse, On y danse

(On the bridge of Avignon, there we dance, there we dance)

—Fifteenth-century song and children’s rhyme

The indisputable sovereign of the southern Rhône wines is Châteauneuf-du-Pape, a strong, earthy red that was among the first French wines to receive an AOC (appellation d’origine contrôlée) after the invention of the classification scheme in the early twentieth century. Its distinctive terroir is centered around the village that bears the same name, which translates to New Castle of the Pope. It thus serves as a viticultural legacy of a brief yet pivotal era in the history of France and the Catholic Church, known forevermore as the “Avignon papacy.” It’s a tale replete with fantastic castles, poisonous plots, and antipopes—legends that have endured for far longer than the complicated politics that brought them into being.

If we return to the days of Philip the Fair, in the early 1300s, we may remember it was a newly elected French pope, Clement V, who allowed Philip to suppress the Knights Templar. Clement had been elected on the strength of his skills as a diplomat, at a time when relations between France and the papacy were severely strained. As one of his main tasks was to enact some sort of reconciliation with the French king, he decided to take up residence in Avignon. Its location on the Rhône, not far from the Mediterranean and Italian shores, made it a convenient location for traveling around Europe. A large tract of territory next to Avignon was actually owned by the papacy. And Rome was a dangerous place at that time, torn apart by power struggles among its leading families, leaving the pope extremely vulnerable. In fact, so volatile was the capital that it was not unusual then for the popes to reside outside of Rome. Clement broke new ground, however, in deciding to reside outside of Italy entirely, and in leaving a long line of popes after him in the same location. This era, in which seven consecutive French popes remained ensconced in the pleasurable idyll of Provence, is known as the Avignon papacy.

The Italians, needless to say, were not pleased by this papal abandonment. Critics referred to the Avignon papacy as the “Babylonian captivity,” arguing that the papacy had been subordinated to the French kings and the spiritual integrity of the Church had been compromised. In Dante’s Inferno, Clement V is depicted in the eighth circle of hell.

Yet this terrible sinner left a rather heavenly legacy here in the earthly realm: Château Pape Clément, produced near Bordeaux. Before becoming pope, Clement had been archbishop of Bordeaux, and there he received a vineyard in donation. He cultivated it carefully and extended its size. When he became pope, the vineyard became known as Vigne du Pape-Clément. The vineyard still has a very good reputation today, producing mainly rich and fruity wines. It can arguably claim to be one of the oldest wine-producing establishments in the Bordeaux wine region.

After Pope Clement died near Avignon in 1314, rival factions in the Sacred College of Cardinals were incapable of agreeing on a new pope. After two years, the French king essentially forced them to a vote, and they elected a frail, seventy-two-year-old French cardinal who became John XXII. Their hope was that he would have a short reign, during which each faction could strengthen its position for the next election. But their hopes were dashed, as John XXII went on to reign for eighteen years (some say his apparent ill-health had all been an act). He had previously been the bishop of Avignon and was happy to stay in place, given the continuing turmoil in Rome. His longevity was often attributed to one of his strange eating habits: he preferred to eat mainly white food products, such as milk, egg whites, white fish, chicken, and cheese. A gastronomic specialty of Avignon known as papeton d’aubergines, a sort of flan made with the (white) flesh of eggplants and originally shaped like the papal hat, is sometimes said to have originated during his reign.

The greatest gastronomic legacy of John XXII was not to be eggplants, however. In an effort to periodically escape the intrigues of Avignon, he established a summer residence in a small place now called Châteauneuf-du-Pape, in the Rhône Valley north of the city........MUCH MORE