...Meantime, secure on Garraway cliffs,

A savage race, by shipwrecks fed,

Lie waiting for the foundered skiffs,

And strips the bodies of the dead."

Harsh.A savage race, by shipwrecks fed,

Lie waiting for the foundered skiffs,

And strips the bodies of the dead."

(He lost money in the South Sea bubble)

From The Public Domain Review:

In contrast to today’s rather mundane spawn of coffeehouse chains, the London of the 17th and 18th century was home to an eclectic and thriving coffee drinking scene. Dr Matthew Green explores the halcyon days of the London coffeehouse, a haven for caffeine-fueled debate and innovation which helped to shape the modern world.

A disagreement about the Cartesian Dream Argument (or similar) turns sour. Note the man throwing

coffee in his opponent’s face. From the frontispiece of Ned Ward’s satirical poem Vulgus Brittanicus

(1710) and probably more of a flight of fancy than a faithful depiction of coffeehouse practices

From the tar-caked wharves of Wapping to the gorgeous lamp-lit squares of St James’s and Mayfair, visitors to eighteenth-century London were amazed by an efflorescence of coffeehouses. “In London, there are a great number of coffeehouses”, wrote the Swiss noble César de Saussure in 1726, “…workmen habitually begin the day by going to coffee-rooms to read the latest news.” Nothing was funnier, he smirked, than seeing shoeblacks and other riffraff poring over papers and discussing the latest political affairs. Scottish spy turned travel writer John Macky was similarly captivated in 1714. Sauntering into some of London’s most prestigious establishments in St James’s, Covent Garden and Cornhill, he marvelled at how strangers, whatever their social background or political allegiances, were always welcomed into lively convivial company. They were right to be amazed: early eighteenth-century London boasted more coffeehouses than any other city in the western world, save Constantinople.

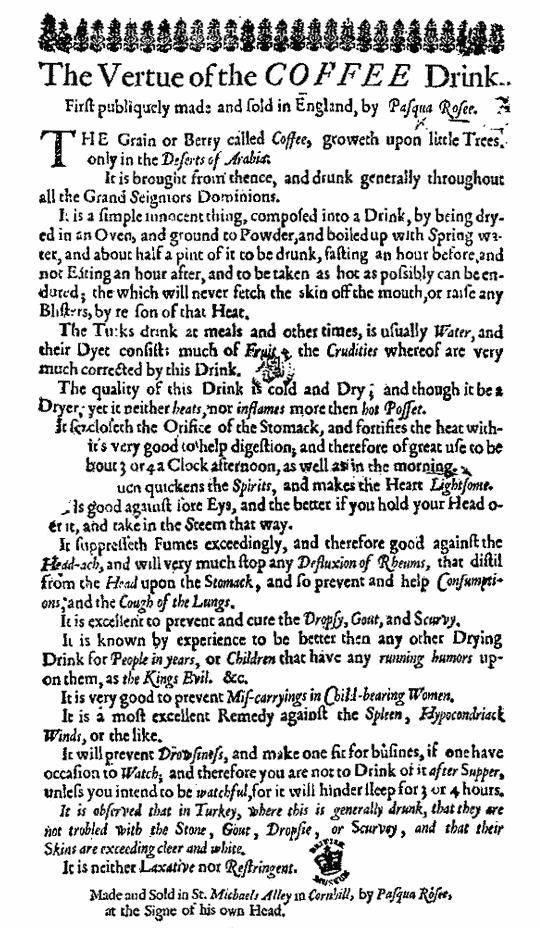

London’s coffee craze began in 1652 when Pasqua Rosée, the Greek servant of a coffee-loving British Levant merchant, opened London’s first coffeehouse (or rather, coffee shack) against the stone wall of St Michael’s churchyard in a labyrinth of alleys off Cornhill. Coffee was a smash hit; within a couple of years, Pasqua was selling over 600 dishes of coffee a day to the horror of the local tavern keepers. For anyone who’s ever tried seventeenth-century style coffee, this can come as something of a shock — unless, that is, you like your brew “black as hell, strong as death, sweet as love”, as an old Turkish proverb recommends, and shot through with grit.

It’s not just that our tastebuds have grown more discerning accustomed as we are to silky-smooth Flat Whites; contemporaries found it disgusting too. One early sampler likened it to a “syrup of soot and the essence of old shoes” while others were reminded of oil, ink, soot, mud, damp and shit. Nonetheless, people loved how the “bitter Mohammedan gruel”, as The London Spy described it in 1701, kindled conversations, fired debates, sparked ideas and, as Pasqua himself pointed out in his handbill The Virtue of the Coffee Drink (1652), made one “fit for business” — his stall was a stone’s throw from that great entrepôt of international commerce, the Royal Exchange.

The meteoric success of Pasqua’s shack triggered a coffeehouse boom. By 1656, there was a second coffeehouse at the sign of the rainbow on Fleet Street; by 1663, 82 had sprung up within the crumbling Roman walls, and a cluster further west like Will’s in Covent Garden, a fashionable literary resort where Samuel Pepys found his old college chum John Dryden presiding over “very pleasant and witty discourse” in 1664 and wished he could stay longer — but he had to pick up his wife, who most certainly would not have been welcome.

The earliest known image of a coffeehouse dated to 1674,

showing the kind of coffeehouse familiar to Samuel Pepys

...MUCH MOREHT: Jason Zweig via Abnormal Returns

Here are the main establishments frequented by the stockjobbers and other denizens: