What African drum languages have to do with women’s emancipation, radioactivity, and the future of the web.

Seven MORETHE INFORMATION

The future of information can’t be complete without a full understanding of its past. That, in the context of so much more, is exactly what iconic science writer James Gleick explores in The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood — the book you’d have to read if you only read one book this year. Flowing from tonal languages to early communication technology to self-replicating memes, Gleick delivers an astonishing 360-degree view of the vast and opportune playground for us modern “creatures of the information,” to borrow vocabulary from Jorge Luis Borges’ much more dystopian take on information in the 1941 classic, “The Library of Babel,” which casts a library’s endless labyrinth of books and shelves as a metaphor for the universe.

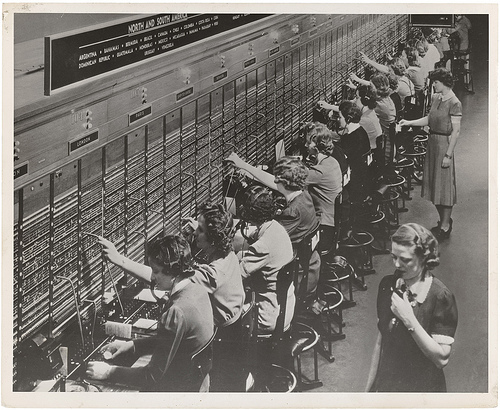

Gleick illustrates the central dogma of information theory through a riveting journey across African drum languages, the story of the Morse code, the history of the French optical telegraph, and a number of other fascinating facets of humanity’s infinite quest to transmit what matters with ever-greater efficiency.

We know about streaming information, parsing it, sorting it, matching it, and filtering it. Our furniture includes iPods and plasma screens, our skills include texting and Googling, we are endowed, we are expert, so we see information in the foreground. But it has always been there.” ~ James GleickBut what makes the book most compelling is that, unlike some of his more defeatist contemporaries, Gleick roots his core argument in a certain faith in humanity, in our moral and intellectual capacity for elevation, making the evolution and flood of information an occasion to celebrate new opportunities and expand our limits, rather than to despair and disengage.

Gleick concludes The Information with Borges’ classic portrait of the human condition:

We walk the corridors, searching the shelves and rearranging them, looking for lines of meaning amid leagues of cacophony and incoherence, reading the history of the past and of the future, collecting our thoughts and collecting the thoughts of others, and every so often glimpsing mirrors, in which we may recognize creatures of the information.”Originally featured here in March.

THE SWERVE

Poggio Bracciolini is the most important man you’ve never heard of.

One cold winter night in 1417, the clean-shaven, slender young man pulled a manuscript off a dusty library shelf and could barely believe his eyes. In his hands was a thousand-year-old text that changed the course of human thought — the last surviving manuscript of On the Nature of Things, a seminal poem by Roman philosopher Lucretius, full of radical ideas about a universe operating without gods and that matter made up of minuscule particles in perpetual motion, colliding and swerving in ever-changing directions. With Bracciolini’s discovery began the copying and translation of this powerful ancient text, which in turn fueled the Renaissance and inspired minds as diverse as Shakespeare, Galileo, Thomas Jefferson, Einstein and Freud.

In The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, acclaimed Renaissance scholar Stephen Greenblatt tells the story of Bracciolini’s landmark discovery and its impact on centuries of human intellectual life, laying the foundations for nearly everything we take as a cultural given today.

This is a story [of] how the world swerved in a new direction. The agent of change was not a revolution, an implacable army at the gates, or landfall of an unknown continent. […] The epochal change with which this book is concerned — though it has affected all our lives — is not so easily associated with a dramatic image.”Central to the Lucretian worldview was the idea that beauty and pleasure were worthwhile pursuits, a notion that permeated every aspect of culture during the Renaissance and has since found its way to everything from design to literature to political strategy — a worldview in stark contrast with the culture of religious fear and superstitions pragmatism that braced pre-Renaissance Europe. And, as if to remind us of the serendipitous shift that underpins our present reality, Greenblatt writes in the book’s preface:

It is not surprising that the philosophical tradition from which Lucretius’ poem derived, so incompatible with the cult of the gods and the cult of the state, struck some, even in the tolerant culture of the Mediterranean, as scandalous […] What is astonishing is that one magnificent articulation of the whole philosophy — the poem whose recovery is the subject of this book — should have survived. Apart from a few odds and ends and secondhand reports, all that was left of the whole rich tradition was contained in that single work. A random fire, an act of vandalism, a decision to snuff out the last trace of views judged to be heretical, and the course of modernity would have been different.”Illuminating and utterly absorbing, The Swerve is as much a precious piece of history as it is a timeless testament to the power of curiosity and rediscovery. In a world dominated by the newsification of culture where the great gets quickly buried beneath the latest, it’s a reminder that some of the most monumental ideas might lurk in a forgotten archive and today’s content curators might just be the Bracciolinis of our time, bridging the ever-widening gap between accessibility and access.

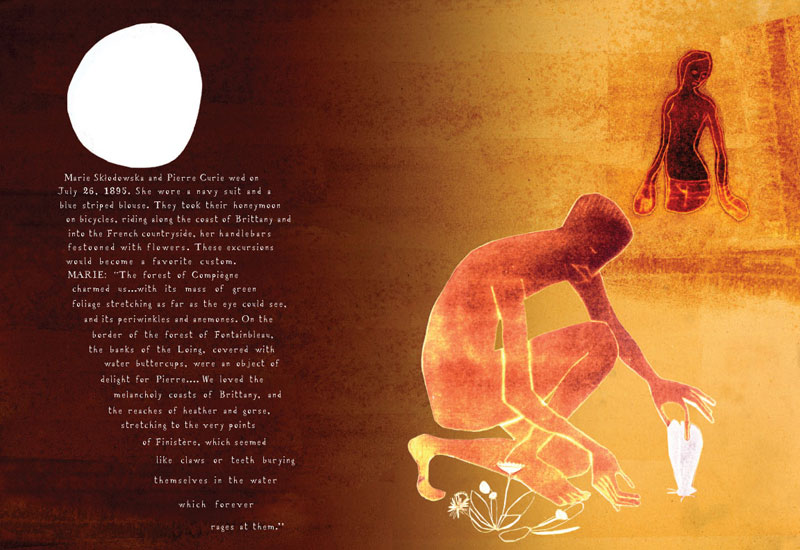

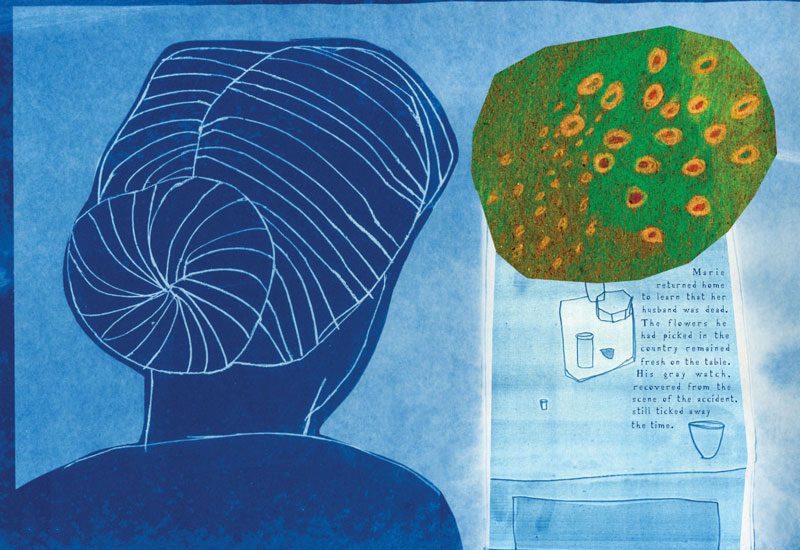

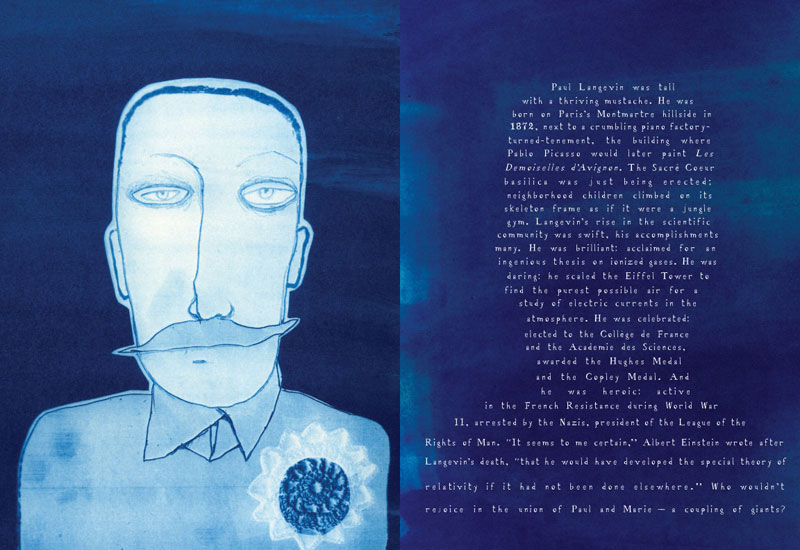

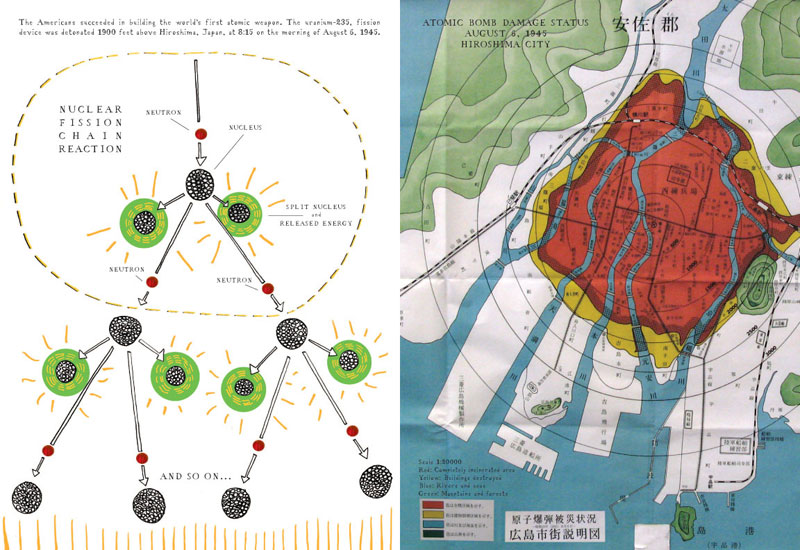

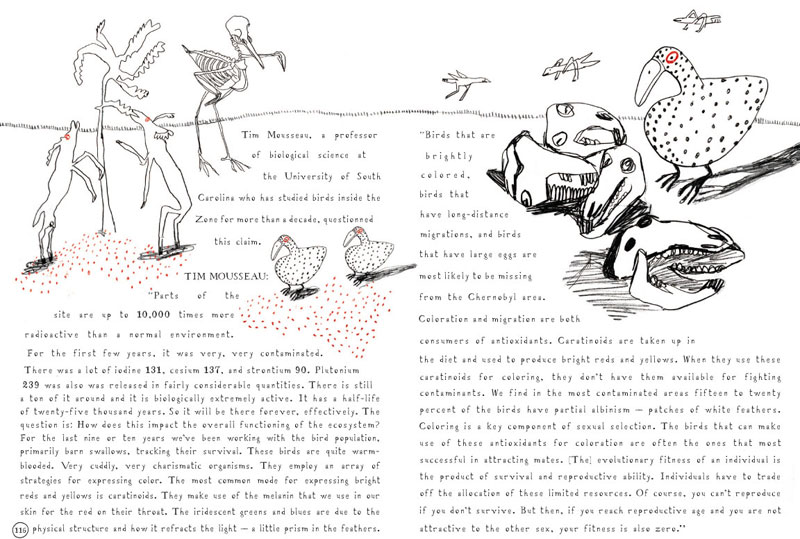

RADIOACTIVE

Wait, how can a book be among the year’s best art and design books, best science books, and best history books? Well, if it’s Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie: A Tale of Love and Fallout, it can. In this cross-disciplinary gem, artist Lauren Redniss tells the story of Marie Curie — one of the most extraordinary figures in the history of science, a pioneer in researching radioactivity, a field the very name for which she coined, and not only the first woman to win a Nobel Prize but also the first person to win two Nobel Prizes, and in two different sciences — through the two invisible but immensely powerful forces that guided her life: radioactivity and love. It’s remarkable feat of thoughtful design and creative vision. To honor Curie’s spirit and legacy, Redniss rendered her poetic artwork in cyanotype, an early-20th-century image printing process critical to the discovery of both X-rays and radioactivity itself — a cameraless photographic technique in which paper is coated with light-sensitive chemicals. Once exposed to the sun’s UV rays, this chemically-treated paper turns a deep shade of blue. The text in the book is a unique typeface Redniss designed using the title pages of 18th- and 19th-century manuscripts from the New York Public Library archive. She named it Eusapia LR, for the croquet-playing, sexually ravenous Italian Spiritualist medium whose séances the Curies used to attend. The book’s cover is printed in glow-in-the-dark ink.

Redniss tells a turbulent story — a passionate romance with Pierre Curie (honeymoon on bicycles!), the epic discovery of radium and polonium, Pierre’s sudden death in a freak accident in 1906, Marie’s affair with physicist Paul Langevin, her coveted second Noble Prize — under which lie poignant reflections on the implications of Curie’s work more than a century later as we face ethically polarized issues like nuclear energy, radiation therapy in medicine, nuclear weapons and more.

Full review, with more images and Redniss’s TEDxEast talk, here.

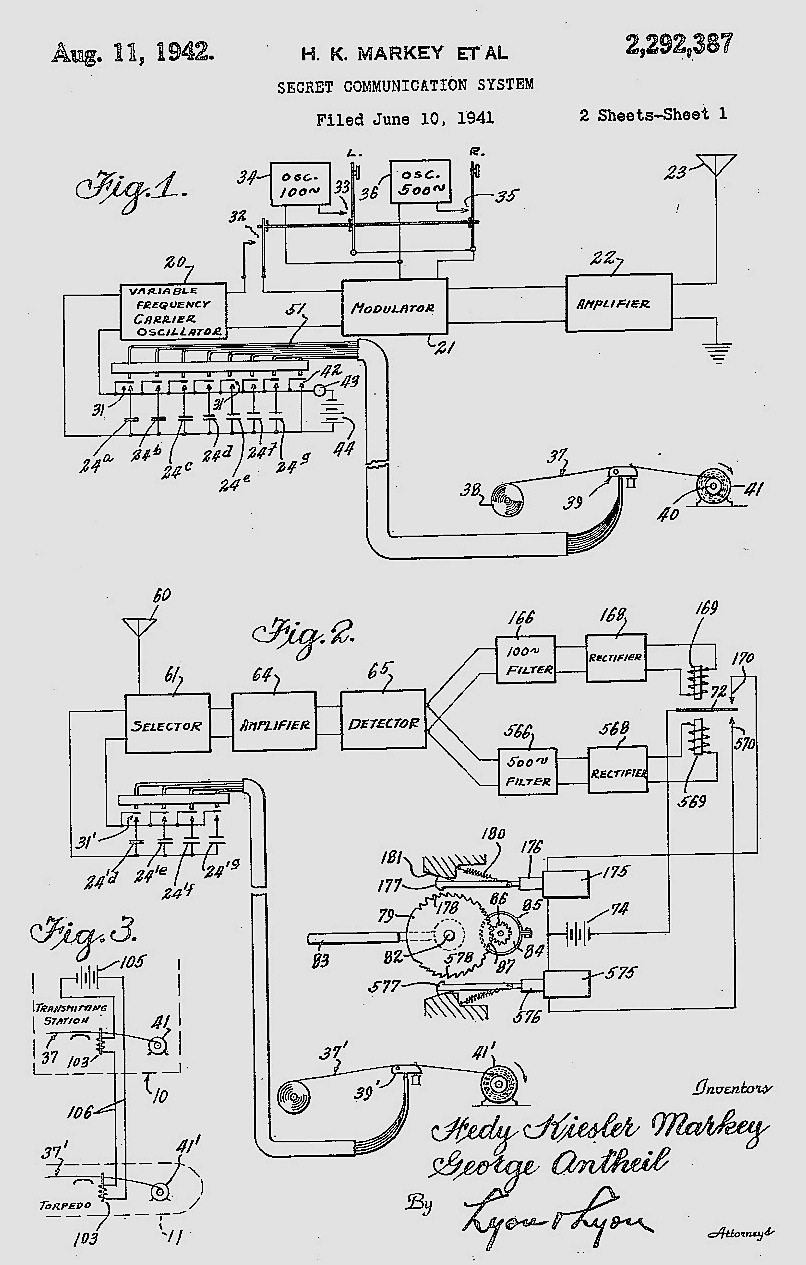

HEDY’S FOLLY

Hedy’s Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World tells the fascinating story of a Hollywood-starlet-turned-inventor whose radio system for remote-controlling torpedoes laid the foundations for technologies like wifi and Bluetooth. But her story is also one of breaking free of society’s expectations for what inventors should be and look like. After our recent review, reader Carmelo “Nino” Amarena, an inventor himself, who interviewed Lamarr in 1997 shortly before her death, captures this friction in an email:

Ever since I found out back in 1989 that Hedy had invented Spread Spectrum (Frequency Hopping type only), I followed her career historically until her death. My interview with her is one of the most notable memories I have of speaking with an inventor, and as luck would have it, she was underestimated for nearly 60 years on the smarts behind her beauty. One of the things she said to me in our 1997 talk was, ‘my beauty was my curse, so-to-speak, it created an impenetrable shield between people and who I really was’. I believe we all have our own version of Hedy’s curse and trying to overcome it could take a lifetime.”In 1937, the dinner table of Fritz Mandl — an arms dealer who sold to both sides during the Spanish Civil War and the third richest man in Austria — entertained high-ranking Nazi officials who chatted about the newest munitions technologies. Mandl’s wife, a twenty-four-year-old former movie star, whom he respected but also claimed “didn’t know A from Z,” sat quietly listening. Hedy Kiestler, whose parents were assimilated Jews, and who would be rechristened by Louis B. Meyer as Hedy Lamarr, wanted to escape to Hollywood and return to the screen. From these dinner parties, she knew about about submarines and wire-guided torpedoes, about the multiple frequencies used to guide bombs. She knew that she had present herself as the glamorous wife of an arms dealer. And she knew that in order to leave her husband, she would have to take a good amount of this information with her.

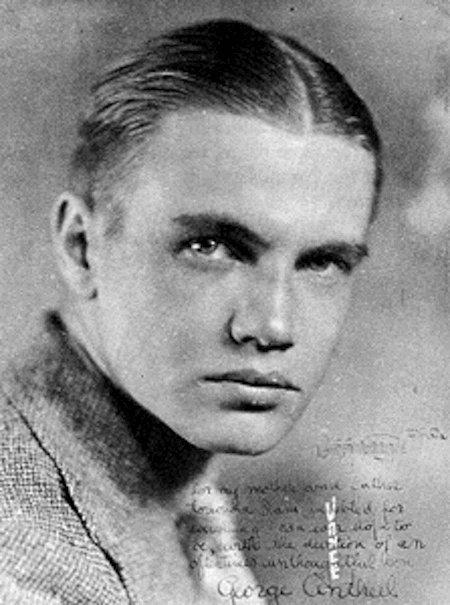

Hedy’s story is intertwined with that of American composer George Antheil, who lived during the 1920s with his wife in Paris above the newly opened Shakespeare and Company, and who could count among his friends Man Ray, Ezra Pound, Louise Bryant, and Igor Stravinsky. When Antheil attended the premiere of Stravinsky’s Les Noces, the composer invited him afterward to a player piano factory, where he wished to have his work punched out for posterity. There, Antheil conceived of a grand composition for sixteen player pianos, bells, sirens, and several airplane propellers, which he called his Ballet mecanique. When he premiered the work in the US, the avant-garde composition proved a disaster.

Antheil and his wife decamped for Hollywood, where he attempted to write for the screen. When Antheil met Hedy, now bona fide movie star, in the summer of 1940 at a dinner held by costume designer Adrian, they began talking about their interests in the war and their backgrounds in munitions (Antheil had been a young inspector in a Pennsylvania munitions plant during World War I.) Hedy had been horrified by the German torpedoing of two ships carrying British children to Canada to avoid the Blitz, and she had begun to think about a way to control a torpedo remotely, without detection.

Composer George Antheil during the 1920s in Paris, when he was living above the newly founded Shakespeare & Co with his wife.

Hedy had the idea for a radio that hopped frequencies and Antheil had the idea of achieving this with a coded ribbon, similar to a player piano strip. A year of phone calls, drawings on envelopes, and fiddling with models on Hedy’s living room floor produced a patent for a radio system that was virtually jam-proof, constantly skipping signals.

Antheil responded to Hedy’s enthusiasm, although he thought her sometimes scatterbrained, and Hedy to Antheil’s mechanical focus as a composer. The two were always just friends and respected one another’s quirks. Antheil wrote to a friend about a new scheme Hedy was planning with Howard Hughes:

Hedy is a quite nice, but mad, girl who besides being very beautiful indeed spends most of her spare time inventing things—she’s just invented a new ‘soda pop’ which she’s patenting—of all things!”Hedy’s Folly isn’t the story of a science prodigy or a movie star with a few hobbies, it’s a star-studded picaresque about two undeniably creative people whose interests and backgrounds unlocked the best in one another — the mark of true inventors.

In the center, Heddy Lamarr, with George Antheil to the right and his wife Boski Antheil to the left

Adapted from Michelle Legro’s fantastic full review.