Lewis Lapham at Lapham's Quarterly:

It is not difficult to be wise occasionally and by chance,

but it is difficult to be wise assiduously and by choice.

—Joseph Joubert

The evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins

posts the odds on the chance encounter and then fertile union of sperm

and egg in my mother’s womb at a number outnumbering the sand grains of

Arabia. Long odds, but longer still because “the lottery starts before

we are conceived. Your parents had to meet, and the conception of each

was as improbable as your own.” Work back the thread of lucky breaks

through all the antecedents animal, vegetable, and mineral that are the

sum of mankind’s time on earth, and wherefrom consciousness and pulse if

not at the hand of the bountiful blind woman, Dame Fortune?

The incalculable run of luck I’m unable to comprehend as a number; I

hear it as a sound. Thirty-five years ago in a labor room at New York

Hospital, the sonogram of my wife’s belly picking up the heartbeat of my

youngest child on final approach to the light of the sun. He’d come a

long way. Atoms wandering in the abyss, then in the womb for the nine

months during which a human embryo ascends through a sequence touching

on over 3 billion years of evolutionary change, up from the shore of a

prehistoric sea, traveling as amphibian, fish, bird, reptile, lettuce

leaf, and mammal to a room with a view of the Queensboro Bridge. I heard

the sound then, hear it now, as the chance at a lifetime shaped from

the dust of a star.

Albert Einstein

didn’t wish to believe that God “plays dice with the world,” but the

equations posted on the blackboards of twentieth-century physics—among

them Einstein’s own proof of wave-particle duality, Werner Heisenberg’s

uncertainty principle, Max Planck’s quantum mechanics—suggest that

chance is a force of nature as fundamental as gravity. So does the

consensus of opinion in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly. Except for sixteenth-century theologian John Calvin,

who believed there is no such thing as fortune and chance, that “all

events are governed by the secret counsel of God,” the witnesses called

to testify on the pages that follow regard Dame Fortune as a presence to

be reckoned with, visible to the eye of history, glimpsed across the

bridges of memory and metaphor in the words of the occasionally wise.

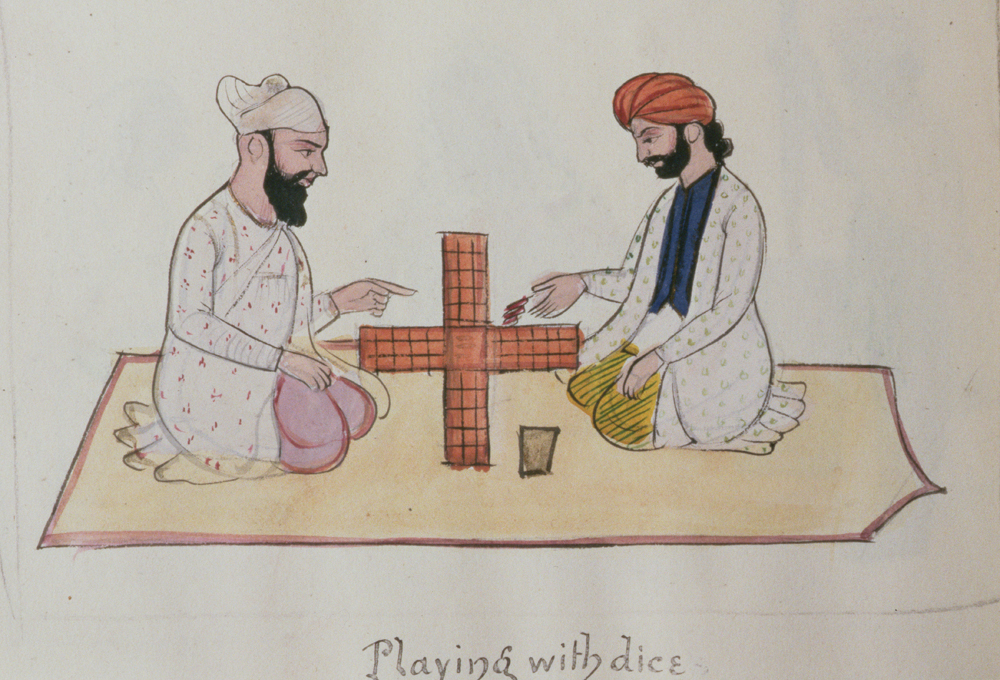

Playing with Dice, Lahore, India, c. 1890. © Royal Asiatic Society, London / Bridgeman Images.

Heisenberg conceived of all facts as momentary perceptions of probability; so did Titus Lucretius Carus, the Roman poet who in the first century BC composed the 7,400 lines of lyric but unrhymed verse On the Nature of Things

infused with the thought of Greek philosopher Epicurus, who in the

third century BC taught that the universe consists of atoms and void and

nothing else. No afterlife, no divine retribution or reward, nothing

other than a vast turmoil of creation and destruction, the elementary

particles of matter (“the celestial seeds of things”) constantly in

motion, colliding and combining in the inexhaustible wonder of

everything that exists—sun and moon, the wind and the rain, “bright

wheat and lush trees, and the human race, and the species of beasts.”

Thomas Jefferson, when asked for the source of his philosophy, identified himself as “an Epicurean,” listing On the Nature of Things

among the books from which he never ceased learning. He borrowed from

it in 1826 to petition the Virginia state legislature for permission to

dispose by lottery enough of his property at Monticello to settle a

$100,000 debt. The legislature twice denied permission on the ground

that games of chance are immoral. Jefferson had posed the question:

But what is chance? Nothing happens in this world without

a cause. If we know the cause, we do not call it chance; but if we do

not know it, we say it was produced by chance…If we consider games of

chance immoral, then every pursuit of human industry is immoral; for

there is not a single one that is not subject to chance, not one wherein

you do not risk a loss for the chance of some gain.

The legislature reconsidered its decision, but before a lottery could

be held Jefferson died bankrupt, his family forced to sell the property

at a price favoring the buyers. One man’s gain, another man’s loss, but

no moral in the tale because reality makes itself up as it goes along, a

near infinite number of atoms encountering one another at unstable

moments in time, made temporarily manifest as bank balance, bonobo, or

butterfly. If physics is nature and nature is God (three worknames for

the same tradecraft), God is free to throw dice with cause and effect

because all the skin in the game is his own.....

....

MUCH MORE