People don't like being manipulated and are much better at detecting it than media, marketeers, politicians, con men and propagandists believe.

From Aeon

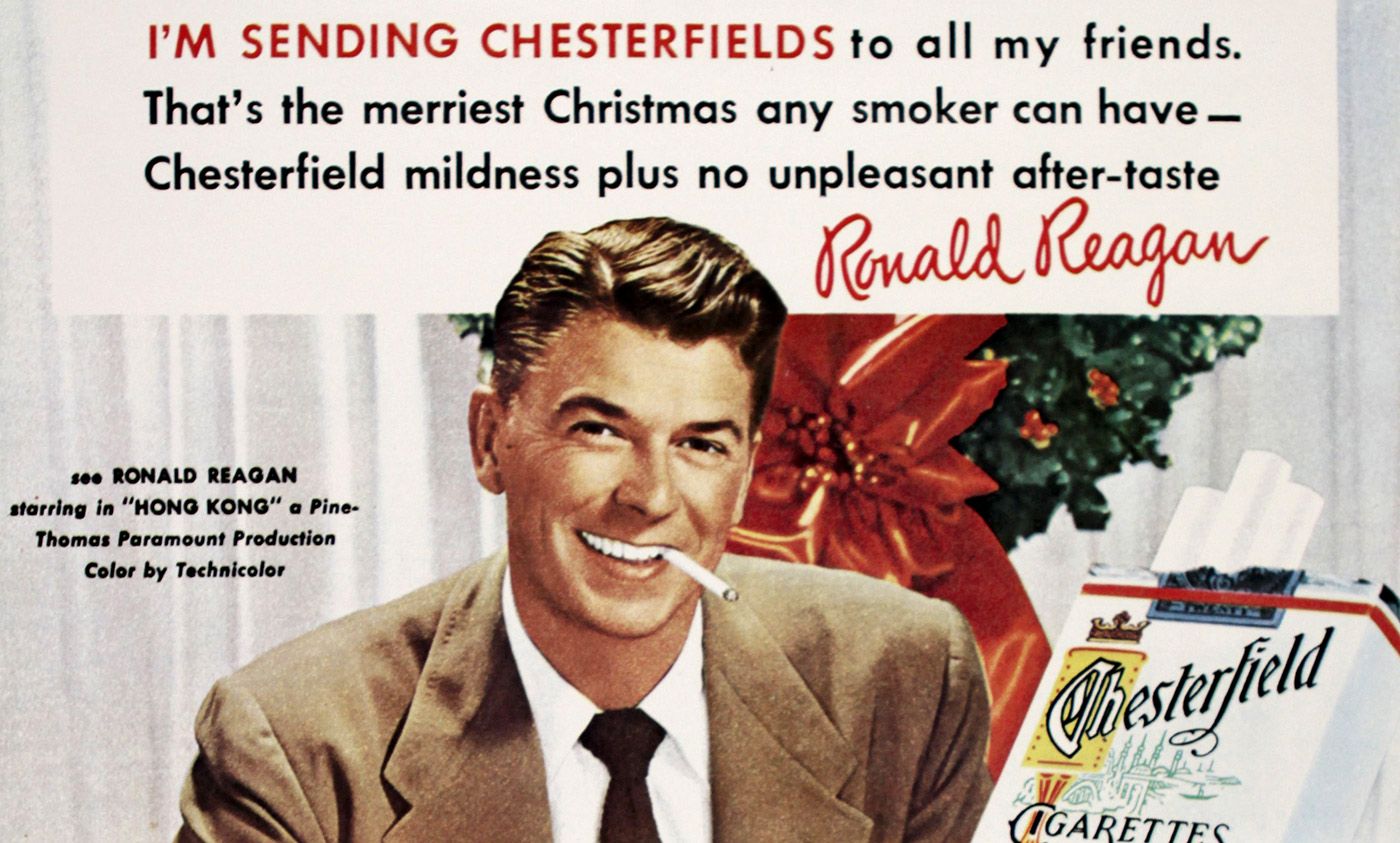

Calling someone manipulative is a criticism of that person’s character. Saying that you have been manipulated is a complaint about having been treated badly. Manipulation is dodgy at best, and downright immoral at worst. But why is this? What’s wrong with manipulation? Human beings influence each other all the time, and in all sorts of ways. But what sets manipulation apart from other influences, and what makes it immoral?We are constantly subject to attempts at manipulation. Here are just a few examples. There is ‘gaslighting’, which involves encouraging someone to doubt her own judgment and to rely on the manipulator’s advice instead. Guilt trips make someone feel excessively guilty about failing to do what the manipulator wants her to do. Charm offensives and peer pressure induce someone to care so much about the manipulator’s approval that she will do as the manipulator wishes.Advertising manipulates when it encourages the audience to form untrue beliefs, as when we are told to believe that fried chicken is a health food, or faulty associations, as when Marlboro cigarettes are tied to the rugged vigour of the Marlboro Man. Phishing and other scams manipulate their victims through a combination of deception (from outright lies to spoofed phone numbers or URLs) and playing on emotions such as greed, fear or sympathy. Then there is more straightforward manipulation, perhaps the most famous example of which is when Iago manipulates Othello to create suspicion about Desdemona’s fidelity, playing on his insecurities to make him jealous, and working him up into a rage that leads Othello to murder his beloved. All these examples of manipulation share a sense of immorality. What is it that they have in common?

Perhaps manipulation is wrong because it harms the person being manipulated. Certainly, manipulation often harms. If successful, manipulative cigarette ads contribute to disease and death; manipulative phishing and other scams facilitate identity theft and other forms of fraud; manipulative social tactics can support abusive or unhealthy relationships; political manipulation can foment division and weaken democracy. But manipulation is not always harmful.Suppose that Amy just left an abusive-yet-faithful partner, but in a moment of weakness she is tempted to go back to him. Now imagine that Amy’s friends employ the same techniques that Iago used on Othello. They manipulate Amy into (falsely) believing – and being outraged – that her ex-partner was not only abusive, but unfaithful as well. If this manipulation prevents Amy from reconciling, she might be better off than she would have been had her friends not manipulated her. Yet, to many, it could still seem morally dodgy. Intuitively, it would have been morally better for her friends to employ non-manipulative means to help Amy avoid backsliding. Something remains morally dubious about manipulation, even when it helps rather than harms the person being manipulated. So harm cannot be the reason that manipulation is wrong.

Perhaps manipulation is wrong because it involves techniques that are inherently immoral ways to treat other human beings. This thought might be especially appealing to those inspired by Immanuel Kant’s idea that morality requires us to treat each other as rational beings rather than mere objects. Perhaps the only proper way to influence the behaviour of other rational beings is by rational persuasion, and thus any form of influence other than rational persuasion is morally improper. But for all its appeal, this answer also falls short, for it would condemn many forms of influence that are morally benign....

....MUCH MORE

And from 2014 the related question:

Big Four Accountant Partners: "Does Kant’s definition or Augustine’s and Aquinas’s definition of evil as privatio boni in subjecto..."One of the more interesting philosophical juxtapositions to be found at the moment.Francine McKenna writing at re: The Auditors:

Are All Big Four Partners Evil Or Just Leadership? Pondering The Problem of Evil