From UnHerd, December 18:

“Today’s Germany is the best Germany the world has seen.” So effused the Washington Post columnist George F. Will five long years ago. It’s hard to imagine anyone — even a German — writing those words today. The country is in crisis. On Monday, Chancellor Olaf Scholz lost a humiliating no-confidence vote, and now Germany is hurtling towards a divisive snap election in February. The nation’s economy has barely grown since 2018, and it is de-industrialising at an alarming rate. The unfolding calamity represents a strategic opening for China and Russia which the West cannot afford to ignore.

At the root of Germany’s industrial woes is electricity, which is now nearly twice as expensive as it is for their American counterparts, and three times more expensive than in China. Prices have been rising since the early 2000s, but a policy embraced by the German government in 2011, following the nuclear meltdown at Fukushima, sealed the nation’s fate. The proponents of the Energiewende (“energy revolution”) policy made the astonishing argument that Germany could rapidly abandon both fossil fuels and nuclear energy without losing its industrial edge. This was, as one Oxford study put it, a “gamble”. Or a game of Russian roulette, a cynic might have added.

The gamble hasn’t paid off. Even Germany’s gas-related dealings with Russia — a source of Russo-American tension since the Sixties — couldn’t stop prices rising throughout the 2010s. They were significant enough, however, to make the shock of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 nearly lethal for German industry. Today, electricity prices are at their highest since 2000, with total production hitting its lowest point since then.

This makes it incredibly tough for Germany to compete with China. Not only does Russian gas continue to flow to China in ever greater quantities, but the Chinese are also receiving sanctioned Iranian oil; installing more than 90% of the world’s new coal power capacity; putting the finishing touches on a hydroelectric infrastructure that already generates more power than Japan; and building ever more nuclear power plants. All this has ensured a fundamental manufacturing advantage over Germany.

But there’s more to the tale of German decline than cheap electricity. The past two decades have also witnessed an industrial revolution of sorts: at the turn of the millennium, China churned out cheap junk and not much else. Now, though, it is shaping up to be a formidable and sophisticated rival.

The car industry is a prime example. Today, Chinese electric vehicles are among the best and cheapest in the world, posing a menace to domestic production in Germany and the rest of Europe. But this was not always the case. As one post on r/CarTalkUK, a Reddit group with half-a-million users, puts it: “I remember only a few years ago when Top Gear went to China and showed us all those horrific knock-off death trap shit-boxes that looked like mutilated Minis… now those things are seemingly a thing of the past.” The EU is well aware of this development, having just slapped tariffs on Chinese cars that would make Trump blush. And it’s not just cars — China dominates many key markets, including drones, shipbuilding, solar panels, and wind turbine components to name just a few, and is making strides in other areas too.

Consider its acceleration. The nation started out by hawking junk, leveraging cheap labour to build up healthy export surpluses. This provided Chinese companies with the cash to invest in moving up the supply chain and, critically, to go shopping abroad. In 2004 and 2005, Chinese state-owned enterprises bought up F Zimmerman and Kelch, two of the world’s leading machine tool companies whose highly specialised equipment is vital for thousands of manufacturing processes. Of course, buying companies doesn’t necessarily hand its new owners the keys to the kingdom: transferring high-end R&D and manufacturing processes to China and training up loyal Chinese engineers and scientists who won’t emigrate can still be scuppered by export control laws, union action, political intervention and so on. But it’s a pretty useful strategy that sooner or later creates opportunities....

....MUCH MORE

The German acquiescence to the purchase of the best in class concrete-pump manufacturer caught our eye in 2012:

The Invisible Hand Touches Germany in No-no Place: China Grabs Putzmeister

It's part of a national strategy.

Things got to the point that we were running this graphic once a year. Here's a 2020 iteration:

"China’s targeted corporate shopping spree to continue, especially in Europe"

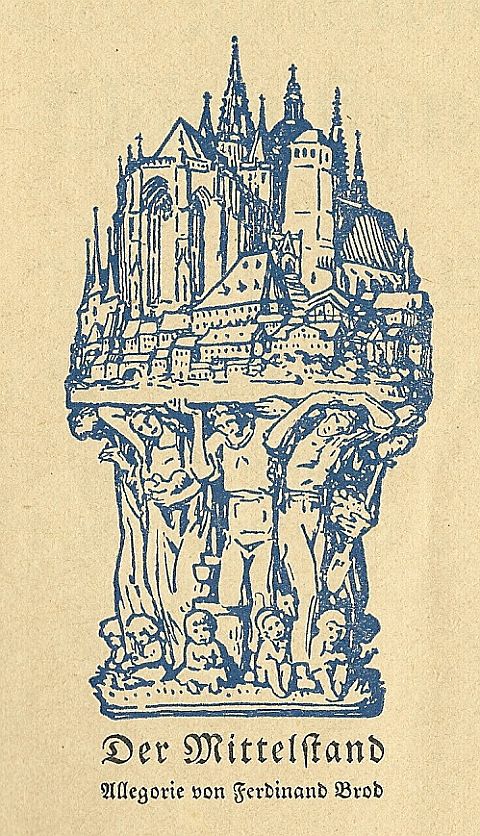

...The German concern for their small and medium sized enterprises goes back quite a ways. Here's an old-timey pic via Wikipedia:

role of the Mittelstand in Walter Wilhelms

„Mission des Mittelstandes“ (Mission of the Mittelstand, 1925)

But without the charm.

Which was followed by: China's COSCO Near Deal To Buy Into Port Of Hamburg