From Kitco, April 23 (also on blogroll at right):

Copper: the linchpin of ancient and modern society we need to find a lot more of

As the third most-consumed metal on the planet, behind iron ore and aluminum, copper is all around us. Found naturally in the Earth's crust, copper was among the first metals used by early humans, dating back to the 8th century, BC.

Three thousand years later homo sapiens figured out how to smelt copper from its ore, and to alloy it with tin to create bronze. Bronze was useful for tools and weapons, making it one of the most important inventions in the history of civilization.

The Copper Age

Nothing happens without copper; as it turns out, not even civilization itself. Beginning around 5,000 BC, the "Chalcolithic" (from the Greek "khalkos" for copper and "lithos" for stone) or Copper Age was a transitionary period between the Neolithic (Stone Age) and the Bronze Age.

It was during this time that copper was introduced as a material that could be worked into metal, paving the way towards the use of bronze later on.

Before that, utilitarian stone objects were fashioned out of flint, mined in small (by today's standards) underground caverns using rudimentary tools. In England between 2,500 and 3,000 BC, ancient miners employed picks shaped from antler bones to get at the glassy black rock which could be broken into sharp pieces used for example to build houses or canoes.

The archeological site of Belovode in present-day Serbia holds the distinction as the world's oldest copper-smelting location, circa 5,000 BC. Copper was also found in the Near East beginning in the late 5th millennium BC. Later, pockets of copper technology began appearing in northern Italy and along the Mediterranean coast.

Eventually, ancient prospectors moved north, bringing their way of life and then-radical metalworking technology with them. So much of what have today is made of metal, but 4,500 years ago, there was nothing but crude dwellings and monuments built of stone and earth. The arrival of metal catapulted early Britain and other societies, including China, which has a long history of using metal objects, into a whole new chapter of civilization.

In the British Isles, the first copper mines were dug into the hills of southwestern Ireland. There, on the shores of an ancient lake, green and blue oxidized rocks betray the tell-tale signs of copper mineralization.

Neolithic people noticed the host limestone rocks were streaked with glittering copper minerals, but without knowledge of mining, little was done with them. It wasn't until these first Britons came into contact with people from Europe, that mining and smelting copper began.

Some of the earliest copper axes can be traced to the Ross Island copper mine in Ireland. Archeologists found stone hammers with grooves in the center used to attach wooden handles, that pounded the rock into tiny pieces. Ancient metal workers used bellows to heat fires to a high enough temperature to melt the rock into glowing metal that, when cooled, hardened into copper that was shaped into tools and decorative objects.

Copper axes from this period were circulated all over Ireland and into western Britain, suggesting the beginnings of the first trade routes.

The Copper Age brought with it a social as well as a technological revolution. The raw material found in the hills of Ireland, and the technology that transformed it into copper are, in many ways, the very foundations of our modern world.

The "Beaker" people, named from the pottery vessels they buried their dead with, brought a new culture from central Europe that spread across Britain. The UK's oldest metal objects were identified in a grave known as the Amesbury Archer, located in Wiltshire around 2,300 BC.

The fact that the individual was buried with copper knife blades, a "cushion stone" used for finishing metal, and gold jewelry, suggests an individual who knew how to get metal and how to work metal.

The grave is also significant because it shows for the first time, people were buried as individuals, with grave goods, suggesting a strong sense of self. Copper Age graves also conferred status.

For early Britons this would've been radical thinking. It compares to stone-age Britain, when people were buried in communal tombs, and which reached its peak in cosmically aligned monuments, like Stonehenge.

Copper may have looked good but it was soft, therefore little better than flint as a cutting or a pounding tool.

The Beakers also knew about tin, which was unlocked from rocks on the coast of Cornwall. Combing copper with the tin mineral cassiterite yielded bronze, which was to propel Britain from the fringes to the technological forefront of Europe.

Controlling the bellow speed to reach the perfect temperature for casting, early metal workers knew how using just the right mixture of metals could make an alloy that was hard enough to make useful, durable tools and weapons like swords.

But first came bronze axes, which were collected as objects of status. Indeed, for the first time since the Stone Age, there was a way of getting and demonstrating wealth.

Metals began moving all over the country — for example axes found in Scotland were made from Cornish tin and Irish copper — and a new class of people emerged to control metals production and trade. It's estimated around a quarter of the population at that time was involved in this economic activity, with some of them becoming fabulously rich.

During the Bronze Age, natural harbors and rivers that facilitated trade became important geographical features. To trade with Europe, Britons built boats that were sailed or rowed to the continent.

In 1992 a wooden boat was found buried 20 feet underground in layers of mud. Originally thought to be up to 20 meters long, the "Dover Boat, Kent" find, is the oldest surviving sea-going vessel in the world.

By 1,500 BC Britain was a rich, connected land but one aspect hadn't changed much at all: farming. Most of the population still moved around with the crops and seasons, with little evidence of permanent farms.

This thinking changed in the 1980s with the discovery of the Flag Fen village in Cambridgeshire. This group of Bronze Age roundhouses served as a template for domestic living that lasted for over a thousand years.

The archeological evidence suggests Bronze Age people were peaceful and well-nourished from a decent diet. They lived in families and farmed small plots of land.

As the Bronze Age matured, this settled lifestyle led to the very first villages, with houses close together and surrounded by fields. Indeed, the Bronze Age changed the way we related to a place and one another – the idea of living in the same house your whole life, working a plot of land and having permanent neighbors. Up to about 1,500 BC this was shockingly new.

Eventually the Bronze Age succumbed to the Iron Age, and in Britain the glories of Celtic warriors, druids, and kings, then finally the Romans, the building of towns, and the end of pre-history.

The late Bronze Age marked a massive turning point; it was as if we had come of age and could mold the world in our own image. And to think it all started with copper.

Modern-day usage

Sometimes referred to as "Dr. Copper" for its ability to diagnose the state of the global economy, copper is just as essential to modern society as to ancient civilizations — if not more so.

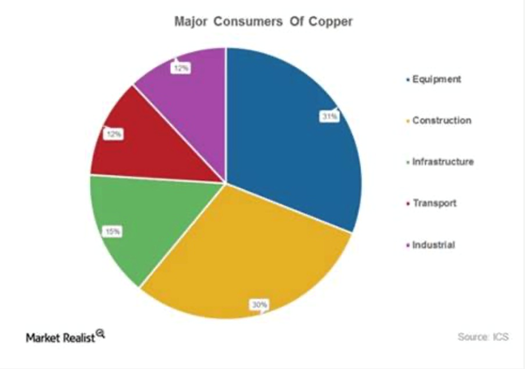

The Copper Development Association divides its uses into four categories: electrical, construction, transport and other. By far the largest sector for copper usage is electrical, at 65%, followed by construction at 25%.

Copper is useful for electrical applications because it is an excellent conductor of electricity.

That, combined with its corrosion resistance, ductility, malleability, and ability to work in a range of electrical networks, makes it ideal for wiring. Among electrical devices that use copper, are computers, televisions, circuit boards, semiconductors, microwaves, and fire prevention sprinkler systems.....

....MUCH MORE