From Mr. Davies' blog at the Financial Times:

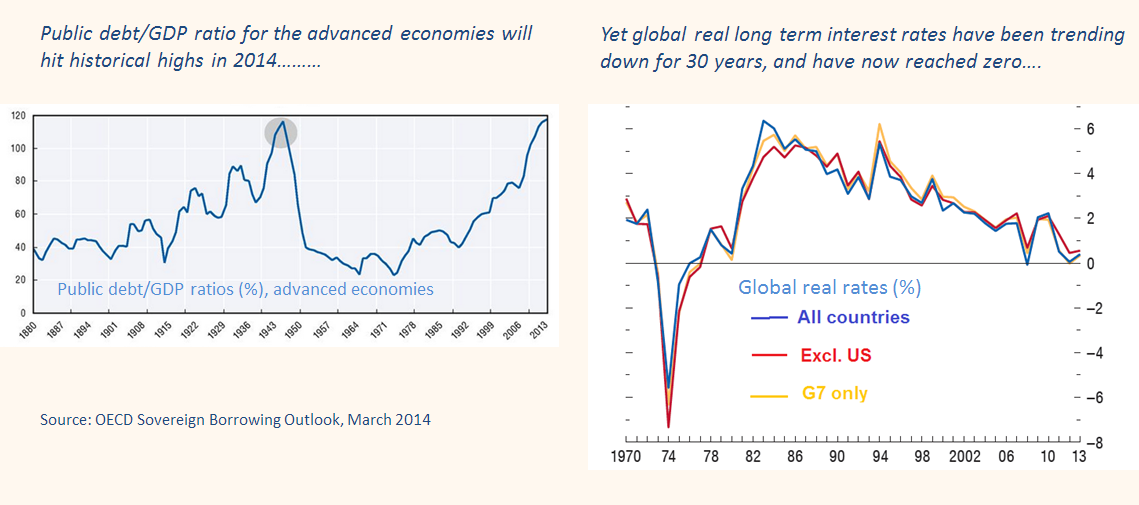

The OECD pointed out

last week that the ratio of public debt/GDP will reach all time

historic highs in 2014, at about 120 per cent. Taken in isolation, this

could certainly viewed as a worrying fact, with bad implications for the

future of real interest rates and possibly inflation. A couple of days

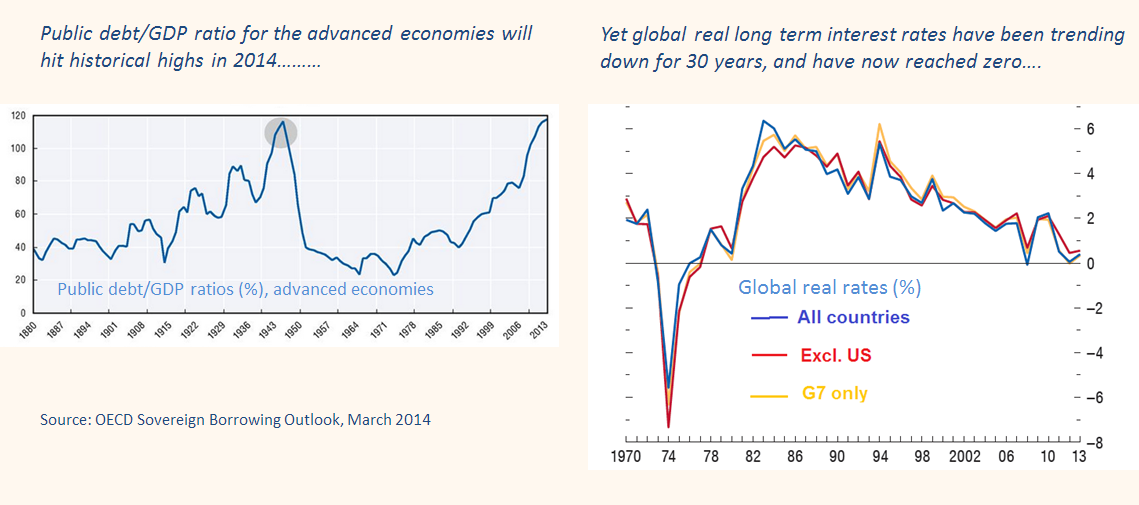

later, however, the IMF published a fascinating chapter in its latest World Economic Outlook (WEO)

on global real interest rates, showing that the global real rate has

fallen from about 6 per cent in the early 1980s to about zero today.

Both of these facts are of course very well known, but placed side-by-side, they still represent a stark contrast:

They also present a conundrum for policy makers and investors. Why

has the surge in public debt not resulted in a large rise in real

borrowing costs for the government, and for the wider economy? And what

does this tell us about the future of the risk free real rate in the

global economy?

The risk free rate is the bedrock of asset valuation, and is often

presented as one of the great “constants” in economic models. But in the

past few decades, it has been anything but constant.

Mainstream macro-economic theory assumes that the global real

interest rate is determined in the market for capital or “loanable

funds”. An upward shift in the demand for capital (from higher

investment or more public debt) will raise real rates, and a rise in the

supply of capital (from higher savings) will reduce them.

Empirical studies generally confirm that the positive association

between public debt and real rates, expected in theory, does indeed

exist (though this is controversial and not well pinned down). Therefore

the strongly negative relationship between the two variables since 1983

is certainly a prima facie puzzle.

The solution lies in the “ceteris paribus”, or other things

equal, clause implicitly inserted into all economic models. Other

things, in this case, have certainly not been equal. While the rise in

public debt, taken on its own, would probably have increased real rates,

other economic forces have worked more powerfully in the opposite

direction.

The IMF says that the main reason for the drop in real rates in the

1980s and 1990s is obvious: the easing in monetary policy that occurred

after the 1979-82 Volcker tightening. After 2000, the IMF identifies

other forces, each of which is associated with a different school of

economic thinking....MORE

HT:

The Big Picture