This one is worth the read.

However, if you are truly sated and the ennui seems unbearable take a look at the little chart after the jump.

From Reason Magazine:

In 1948 Norbert Wiener, the father of cybernetics, wrote an urgent letter to Walter Reuther, the president of the Union of Automobile Workers. Wiener warned Reuther that technologies that combined computing machines with production machinery would soon yield an "apparatus [that] is extremely flexible, and susceptible to mass production, and will undoubtedly lead to the factory without employees; as for example, the automatic automobile assembly line." Wiener ominously concluded, "In the hands of the present industrial set-up, the unemployment produced by such plants can only be disastrous."

The mass unemployment that Wiener predicted did not occur. As technology advanced, the number of employed workers in the United States increased from 59 million in 1950 to a peak of 146 million in 2007, and GDP grew from $2 trillion to $13.6 trillion (in 2005 dollars) between 1950 and 2012.

Now, two centuries after Luddites smashed then-newfangled weaving frames in northern England, predictions of permanent technological unemployment are being revived. In a December working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, called "Smart Machines and Long-Term Misery," the Columbia economist Jeffrey Sachs and the Boston University economist Laurence Kotlikoff pose the question, "What if machines are getting so smart, thanks to their microprocessor brains, that they no longer need unskilled labor to operate?" After all, they point out, "Smart machines now collect our highway tolls, check us out at stores, take our blood pressure, massage our backs, give us directions, answer our phones, print our documents, transmit our messages, rock our babies, read our books, turn on our lights, shine our shoes, guard our homes, fly our planes, write our wills, teach our children, kill our enemies, and the list goes on."

Sachs and Kotlikoff are not alone in worrying how technological progress will affect employment. Last year, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee of MIT's Center for Digital Business published a small book, Race Against the Machine, that looks at trends in U.S. employment and wages. It concludes that the pace of progress "has sped up so much that it's left a lot of people behind. Many workers, in short, are losing the race against the machine." And in a 2011 article for the McKinsey Quarterly, the Santa Fe Institute economist Brian Arthur describes automation as "a second economy that's vast, automatic, and invisible." In Arthur's view, "The primary cause of all of the downsizing we've had since the mid-1990s is that a lot of human jobs are disappearing into the second economy. Not to reappear."

As evidence that American workers are losing to the machines, Brynjolfsson and McAfee point to falling real wages for unskilled workers in the United States. The Employment Policy Institute's 12th State of Working America report reveals that in constant 2011 dollars, the hourly wage for men with less than a high school education fell from $17.50 per hour in 1973 to $12.70 in 2011; wages for men with a high school diploma fell from $20.70 to $17.50 per hour; and even hourly pay for those with some college dropped from $20.20 to $19.50. In the same period, real wages for college-educated men rose from $28.50 to $31.80. Men with graduate degrees saw a gain from $31.70 to $41.30. In addition, Americans are leaving the labor force. Adult workforce participation peaked at 67.3 percent in 2000 and has now fallen to 63.6 percent. This suggests that had the labor force participation rate remained the same as it was in 2000 that the current unemployment rate would be around 13 percent instead of 7.9 percent....MORE

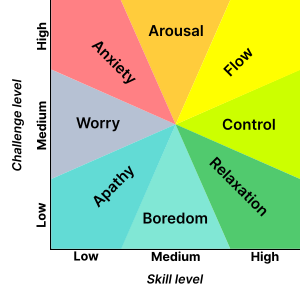

Mental state in terms of challenge level and skill level

Csikszentmihalyi