...MA in mathematics and physics, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. MBA Stanford University. Ph.D. in finance and mathematical economics, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.While I still haven't made up my mind on the role Black-Scholes played in the financial mess, I don't think it was as important as other factors.

After finishing business school, I worked as a management consultant for McKinsey & Co. for a while, but soon found out that business life was not for me. (I did enjoy flying around Europe, though.) After completing my Ph.D. I taught finance and decision sciences at the Wharton School, the Hebrew University and the University of Zurich until I realized that the ivory towers were not for me either. During my time in academia I wrote about 30 research papers for professional journals.In 1987 I started writing for the “Neue Zürcher Zeitung.” I soon realized that this was the kind of work that I liked most! Since the founding of the weekly “NZZ am Sonntag” in March 2002 I have also been writing a monthly column on mathematics....

From the American Interest:

The Math Behind the Meltdown

...Before the 1970s, even though options contracts had existed for centuries, there was no scientific, agreed-upon way to price them. How much should the farmer pay for that fertilizer option? How much should the investor fork out for protection against currency fluctuations? It took hundreds of years of progress in mathematics, physics, statistics and other disciplines for Fischer Black, Myron Scholes and Robert C. Merton to create their formula, which, to put it simply, projected the price of an option by feeding five variables into a partial differential equation: the strike price of the option, the current price of the underlying asset, the risk-free rate, the time to maturity and the volatility of returns of the underlying asset. As it happened, their discovery coincided with the rapid rise of computing power, which enabled traders to apply the formula quickly and inexpensively. The market for options exploded as a result, as contracts could be more confidently priced and then traded as commodities themselves.

Obviously, Black, Scholes and Merton stood on the “shoulders of giants”, as the great sociologist Robert K. Merton, Robert C.’s father, put it in a famous 1985 book. Szpiro takes us back to the origins of modern financial exchanges, and their respective disasters: the Dutch Tulip craze and the Dutch East India Company, the first publicly traded company; and the Paris Bourse, the first French stock exchange, created to boost the disastrous finances of the French monarchy. Both histories richly describe the speculative trading on margin, efforts to get around bans on short-selling, runs, counterparty failures, and market crashes that are now so uncomfortably familiar to us.

But Szpiro soon gets to the meat of the book in his investigation of the lives and research of three French pioneers of financial analysis. Jules Regnault, born in 1834, was the first to attempt a mathematical understanding of bourse activity, and the first to make foundational assertions about efficient markets and the potential for abuse of information. Henri Lefèvre, a secretary to the banker James de Rothschild, created the first known graphical representations of option payouts. And Louis Bachelier, a professor ignored and spurned, laid the foundations for much of modern options analysis. Bachelier was the first to apply Gauss’s bell curve and heat diffusion equations from physics to stock price movements, the first to assert that an option’s value would depend on the volatility of a stock, and one of the first to attempt mathematical and statistical explanations of economic theory.

Szpiro then leaves the world of early financial analysis to describe important innovations elsewhere in science and mathematics that eventually became foundational for the options pricing formula. He shows how the British army doctor and botanist Robert Brown applied the Gaussian error distribution to the irregular, random movement of particles suspended in fluid—Brownian motion. He also dives into the work of Albert Einsten, Marian Smoluchowski, Paul Langevin, Theodor Svedberg, and the politics of Nobel Prize selection. All eventually influenced the emergence of Black-Scholes. He spends a bit more time on Andrei Kolmogorov, who, in a life of prolific mathematical discovery, wrote the axioms that eventually defined the foundations of probability theory, and on the Japanese mathematician Kiyoshi It?, who made breakthroughs in stochastic differential equations. We also learn of the tragic life of Wolfgang Doblin, who died an early death as a soldier fighting the Nazis in World War II. Doblin independently created prototypes of It?’s work that he had hidden for decades in a pli cacheté (a sealed envelope) in the Academie des Sciences in Paris to prevent his work from falling into the hands of the Nazis.

Having surveyed the relevant scientific and mathematical inputs that eventually came together to produce Black-Scholes, Szpiro returns to financial theory in the modern era and specifically to the discovery of the options pricing model. He describes the career of Paul A. Samuelson, the modern origin of mathematical rigor in economics, the politics of Harvard University economics department appointments, and the eventual revival of Bachelier’s work. Then we are introduced to the academic, personal and career histories of Fischer Black, Myron Scholes and Robert C. Merton themselves. We follow them from various departments at Harvard and MIT to the private sector and other destinations beyond. We witness serendipity in science: Their discovery coincided with the opening of the Chicago Board Options Exchange and the explosion of options markets.

The Black-Scholes formula quickly became the industry standard, so much so that it was directly programmed into Texas Instruments calculators for traders. Fame, new professorships, and work on Wall Street quickly followed. Fischer Black died of cancer in 1995 at the age of 57, two years before the Nobel Prize was awarded to the creators of the options pricing formula. Thus, Scholes and Merton, both still very much alive, won the award. (The formula is most frequently called Black-Scholes because these two originally teamed up to work and publish on the subject together, while Merton’s work basically confirmed and expanded upon theirs.)...MUCH MORE

We've looked at some of the same aspects. Here's a Guardian review of Seventeen Equations that Changed the World, "The mathematical equation that caused the banks to crash".

I'll lead with the Hat Tip: Finance Clippings who writes:

A reasonably good account of the impact of the Black Scholes equation. Despite the rather dramatic title of the article, the equation did not cause the market crash.

For my MBA 523 students - you need to read this. We're talking about the derivation of the Black Scholes model this week!

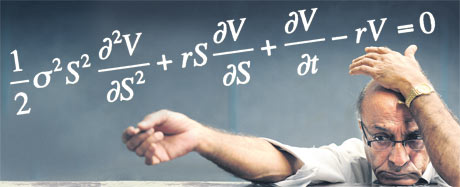

In the Black-Scholes equation, the symbols represent these variables: σ = volatility of returns of the underlying asset/commodity; S = its spot (current) price; δ = rate of change; V = price of financial derivative; r = risk-free interest rate; t = time. Photograph: Asif Hassan/AFP/Getty Images

Okay, not all of B-S but enough that if anyone had been paying attention they could have made money off the young man's work.

I was going to do a post on the King of 19th century put and call brokers but you may find this more interesting.

From Bloomberg:

Wall Street Quants Owe a Debt to Obscure French Student....

Here's a practitioners look at the efficacy of the formula "Why Black-Scholes is Better Than We Think" .

Finally a cautionary tale from a very smart guy:

Personally I ascribe most of the problem to risk models and credit default swaps, usually circling back to JP Morgan's Head of Global Commodities and co-inventor of CDS', Blythe Masters.

From May 2008 (i.e. pre-Lehman) "Finance: 'Blame the models'".

And in no particular order:

How many Nobel Laureates Does it Take to Make Change...And: End of the Universe Puts Inside Wall Street's Black Hole