From VoxEU. May 16:

Authors

Leonardo Gambacorta

Head of Emerging Markets Bank For International Settlements

Vatsala Shreeti

Economist Bank For International Settlements

Advances in AI are transforming the economy. Behind this wave of visible innovation lies a less visible but significant trend: the role of large technology firms – commonly referred to as ‘big techs’ – across the AI supply chain. This column analyses the AI supply chain and the market structure of every input layer, highlighting the economic forces shaping the provision of AI and the role of big techs in each input market. The authors illuminate challenges that big techs pose to consumer choice, innovation, operational resilience, cyber security, and financial stability.

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) are poised to transform the economy and society. From chatbots and image generators to financial forecasting tools, AI applications are becoming ubiquitous, promising to revolutionise the way we live and work. In particular, generative AI (GenAI) is being adopted at a much faster pace than other transformative technologies (Bick et al. 2024). Recent evidence already points to AI’s wide-ranging impact on labour markets and productivity, local economies, women’s employment, capital markets, public finances, and the broader financial sector (Gambacorta et al. 2024, Aldasoro et al. 2024, Albanesi et al. 2025, Andreadis et al. 2025, Frey and Llanos-Parades 2025, Kelly et al. 2025).

Behind this wave of innovation lies a less visible but significant trend: the growing role of large technology firms – commonly referred to as ‘big techs’ – across the AI supply chain. Big techs have been consistently investing in AI: in 2023, they accounted for 33% of the total capital raised by AI firms and nearly 67% of the capital raised by generative AI firms (Financial Times 2023). While big techs have undoubtedly accelerated the development of AI, their expanding influence over how AI is provided raises critical questions about competition, innovation, operational resilience, and financial stability.

In a recent paper (Gambacorta and Shreeti 2025), we explain the AI supply chain and the market structure of each of its input layers. We highlight the economic forces shaping the provision of AI today, and the role of big tech in each input market. We also outline the potential impact of the current market structure on economic outcomes and highlight challenges for regulation.

Big techs in the AI supply chain

The AI supply chain comprises five key layers: hardware, cloud computing, training data, foundation models, and user-facing AI applications (see Figure 1). Each of these layers is essential to powering the AI systems we use today, and big techs are active in all of them.

Consider cloud computing, the backbone of AI development. AI models require immense computational resources for training and deployment, and cloud platforms provide the infrastructure to make this possible. Globally, the cloud market is dominated by three big techs: Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform.

Figure 1 The AI supply chain

Source: Gambacorta and Shreeti (2025).

Together, the three big tech firms control nearly 75% of the infrastructure-as-a-service market, the segment most relevant for AI. Their dominance is rooted in both the economic forces shaping the cloud computing market and their strategic actions. High fixed costs, economies of scale, and network effects make it difficult for smaller players to compete in this market. Moreover, cloud providers also charge egress fees to transfer data out of their platforms. The egress fees charged by big techs not only exceed the incremental cost of transferring data but also exceed the fees charged by smaller competitors (Biglaiser et al. 2024). Big techs also provide vertically integrated service ecosystems on their platforms, often at a discount.

But big techs’ influence extends far beyond cloud computing. Training data is the lifeblood of AI, and big tech firms have access to some of the richest pools of user-generated data in the world. Meta has Instagram, Facebook, and WhatsApp; Google has Gmail, Maps, Play Store, and Google Search; Microsoft has Bing; LinkedIn and Microsoft 365 (Hagiu and Wright 2025). To use these data for AI training, big techs have been quietly updating their terms of use and privacy policies. In addition to exploiting their existing data reserves, big tech companies are actively acquiring or partnering with data-rich firms. As the stock of high-quality public data dwindles, such proprietary data sources will become even more valuable. The increasing returns to every additional unit of data can further entrench their influence over the AI supply chain.

The foundation model layer of the AI supply chain – home to large pre-trained models like OpenAI’s GPT-4 or Google’s Gemini – is another area where Big Techs are increasingly active. Foundation models are expensive to develop, with training costs often exceeding $100 million (The Economist 2023). These high fixed costs can create significant barriers to entry, favouring firms with deep pockets and access to computational resources. 1 Unsurprisingly, big tech firms are not only developing their own foundation models but are also integrating them into their consumer-facing products. Microsoft offers its AI-powered Copilot across its suite of applications, while Google embeds its Gemini model into search results. At the same time, they are producing AI hardware (chips) and even securing their own supply of nuclear fuel to power data centres (CNBC 2024). Such vertical integration allows Big Techs to capture value at multiple points in the supply chain.

Figure 2 Big techs in the AI supply chain

Source: Gambacorta and Shreeti (2025).

This vertical integration can create a self-reinforcing ‘cloud-model-data loop’ (see Figure 2). By controlling cloud computing resources, big tech firms can produce better AI models. These models, in turn, generate more data, which can be fed back into their systems to improve subsequent iterations. The loop is further strengthened if there are substantial network effects associated with AI applications provided by big techs. As more users adopt a particular AI model or platform, its value increases, attracting even more users. The strength of this loop will depend on the quality of big techs’ proprietary data, the extent of network effects arising from AI use, and the returns to scale of each additional unit of data in the AI training process.

Implications for economic and social outcomes....

From FutureBlind:

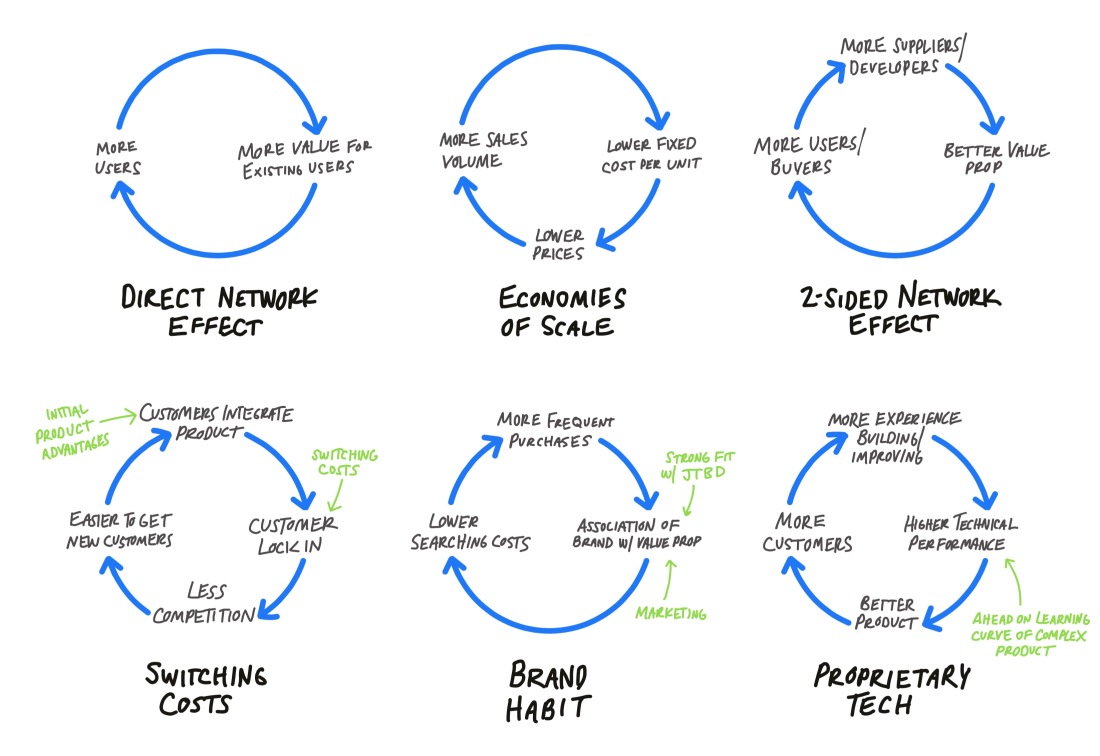

Competitive advantage can be represented visually as 1 or more feedback loops. These create the advantage “flywheel” that maintain and grow a moat over time. Think of a big, heavy wheel that takes some effort to get started but then coasts off its own momentum.

Before continuing, check out Eric Jorgenson’s primer on the flywheel mental model here.

Flywheel archetypes

Here are 6 simple examples of common advantages represented as flywheels (or “causal loops” in systems terminology). These loops are generalized — they’ll be expressed uniquely in every company that has them.

A few examples of how each advantage flywheel can vary:

As Eric discussed in his flywheel post, each wheel needs a push to get started. Written in green on a few of the archetypes above are initial advantages to get the wheels moving. Whether it’s a better user experience, a technical breakthrough, or a bootstrapped network based off of an existing network (college campuses for FB) or a useful utility (Instagram).

- In the Economies of Scale flywheel above, the primary driver of more volume is low prices. This fits for most consumer businesses, but lower prices aren’t always the outcome of lower unit costs. If prices are maintained or increase, scale will yield higher margins → more resources to spend on growth → more sales volume.

- The Brand Habit flywheel exhibits the typical loop for habit-reinforcing association of a brand with a specific quality or job-to-be-done. Think “thirst quenching happiness” for Coca-Cola and “low prices” for Wal-Mart. Another example of brand advantage is more of a social proof effect: Product has success → the cool kids want it → improved perception of product → …

Real world examples

The above archetypes can be combined to create more comprehensive flywheels modeling the driving “engines” of each company’s moat:

The most successful moats have multiple flywheels that feed off of each other’s momentum. Google’s technical advantages enable stronger brand allegiance and vice versa. Coca-Cola’s marketing-driven brand feeds off of it’s distributor/bottler based network effects. Facebook’s brands have at least 3 reinforcing network effects: direct (social network), 2-sided aggregator (advertising and developers), and brand-driven social proof....

....MUCH MORE

As artificial intelligence comes more and more to the fore, the advantages accruing to those companies that can afford to make use of their data and custom train the machines will act as advantage flywheels that shift the distribution of profits from the normal Pareto: 80% of the loot goes to the top 20% of businesses to perhaps as much as 95% of all the profits going to the top 5% of businesses.

I didn't really mean the "eat your heart out HBR" line.Here's the Harvard Business Review on this very point:

HBR—From Pareto To Hyper-Pareto: "AI Is Going to Change the 80/20 Rule"

The Big Get Bigger: "The trade war uncovers new economies of scale"

From Yahoo Finance, April 15:

It pays to be big.

That's one early takeaway from the tariff drama. Investors momentarily poured back into Big Tech after the administration initiated a temporary levy exemption that covers consumer electronics, networking equipment, GPUs, and servers.

It's essentially another way of saying that Big Tech will probably be OK, as investors also look to the sector as a defensive play. Meanwhile, other sectors and companies still stare down a massive tariff upheaval.

It's a feature of American politics to want to avoid the appearance of picking winners and losers in the market. That phrase is often used as a rhetorical cudgel to attack opponents as bad for the economy.

But one person's favoritism is another's industrial policy.

If the market is consumed by the repercussions of tariffs, exemptions to those taxes can mean everything. The potential special carve-outs for tech, however, initially sparked a rally on Monday, fizzled, then rebounded. Part of this confused response from investors was the White House seemingly sending mixed signals.

After the exclusions from reciprocal tariffs were first unveiled, the president said in a social media post "there was no Tariff 'exception' announced." He later told reporters that his goal was encouraging production to move to the US but added that the administration has to show flexibility.

The tech titans hoping to receive assistance from the White House are showing flexibility too, or rather a willingness to support the president's agenda of bolstering domestic manufacturing and investment.

Nvidia (NVDA) on Monday said it will produce up to $500 billion of AI infrastructure in the US within the next four years. That announcement follows other Big Tech commitments from Apple (AAPL), Microsoft (MSFT), and Meta (META) to spend in the US....

....MUCH MORE

This is a corollary of the basic framework for understanding businesses and investing that we've been pitching for the last six or seven years.

If interested see:

Why Do the Biggest Companies Keep Getting Bigger? It’s How They Spend on Tech"

...Much more important than the direct monetization of big data is the strategic advantage it can bestow over time.

In a winner-take-all economy, as in a horse race, small differences in superiority are rewarded all out of proportion to the actual advantage. A top thoroughbred may only be a couple fifths of a second faster than the field but those two lengths over the course of a season can mean triple the earnings for #1 vs. #2.

In commerce the results can be even more dramatic because rather than the 60%/20%/10% purse structure of the racetrack the winning vendor will often get 100% of a customer's business.....

Competitive Advantage and Feedback Loops

Flywheel Effect: Why Positive Feedback Loops are a Meta-Competitive Advantage

"America's Biggest Firms' Moat Is Becoming Impregnable" (TSLA; NVDA; GOOG)

The announcement at the end of August that Tesla was going live with their supercomputer — Elon Got Himself A Supercomputer: "Tesla's $300 Million AI Cluster Is Going Live Today" (TSLA)—reminded me of this piece at ZeroHedge, last month. We'll be back with more on Morgan Stanley's Tesla note later today but for now the TL;dr is "To the victor go the spoils" or "The rich get richer" or "Those who can afford a supercomputer will get closer to discovering the profitability (if any) of AI than those who can't afford a supercomputer."

In Nvidia's World, If You (and your company) Don't Have Money You Will Not Be Able To Compete (NVDA)

The advantage flywheels keep spinning and reinforcing each other to the point that the Pareto distribution of profits - 20% of companies reap 80% of the profits - is becoming Super-Pareto where 5% of the companies reap 95% of the profits and is approaching Hyper-Pareto at maybe 2% of companies reaping 98% of profits.

It all comes down to having the resources to keep up.

I watched Mr. Huang give the keynote and it's all a bit much to digest before firing out comments that would make any sense at all so here are some of today's headlines to give a taste of what the intro paragraph is based on.

These are Nvidia's press releases via GlobeNewswire....

"Elon Musk says any company that isn’t spending $10 billion on AI this year like Tesla won’t be able to compete" (TSLA)

This.

This is such an important concept to grasp. It's the advantage flywheels, the rich get richer, winner-take-all reality of business in 2024....

"Jensen Huang’s extraordinary interview" (NVDA)

And many more, we are playing for keeps.

The Hyper-Pareto Distribution Of Profits Is Happening Right Now (plus an anniversary)

It's not some cutesy management* fad or pop insight like "Business secrets of Genghis Khan."

To the rich go the profits and internalizing that fact makes the rest of this portfolio construction/fund management/investing stuff easier to conceptualize and execute.

And AI is accelerating the already extant dynamic....

Just to

reiterate, every incremental advantage that a company can afford does

not affect income production in isolation. They accrete in sometimes

unforeseeable combinations.

That's it, business, companies and investing in the 21st century. Learn it, love it, live it.

Or not, your call.