From Bot Populi:

Who Learns and Who Profits in the Era of Artificial Intelligence?

Me: My flight was canceled, and I want to check if the refund claim I made yesterday is being correctly processed.

Chatbot: Hmmm. Sorry, I didn’t understand that. I’m a new Chatbot and still learning. I’m better with simple, short questions. If you prefer to choose a topic from our menu, type ‘Help’ (31 March 2023).

Chatbots are not new. Neither is artificial intelligence (AI), for that matter. However, up until recently, the type of questions that chatbots could reply to were extremely simple, and interacting with them was usually frustrating. And while we have been interacting regularly with advanced AI – Google’s search engine and Amazon’s marketplace pricing system being two prominent examples – something has changed since ChatGPT was released in November 2022. Not only was its rate of adoption faster than that for any other platform before, but the effects of integrating ChatGPT, and more generally Large Language Models (LLMs), into our everyday lives have already gone far beyond those we witnessed before.

Still, what continues to remain unchanged is Big Tech dominance: Currently, AI development hugely benefits US Big Tech.

Dominance of US Big Tech over Frontier AI

I asked Bing’s integrated ChatGPT whether Microsoft currently wields intellectual monopoly. Here’s what it responded with: “I’m sorry, but I couldn’t find any recent information about Microsoft being an intellectual monopoly. The most recent information I found was about the United States v. Microsoft Corporation case in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which I mentioned in my previous message. Is there anything else you would like to know?”Judging from the above answer, ChatGPT does not seem to be aware of its own positionality in the Big Tech ecosystem. But US Big Tech companies, in particular Microsoft and Google, today control the AI field, appropriating public research and tapping into scientists’ and intellectual talent from various universities.

While patents seem to be central to Google’s strategy, secrecy is Amazon’s preferred appropriation mechanism, which also explains why it presents less research than the other tech giants in AI conferences.

My research has looked at the US Big Tech dominance of the AI field in detail. As a first step, I proxied the frontier AI research network of actors by plotting the network of organizations with the highest frequency of presentations at the top 14 AI scientific conferences. US and Chinese Big Tech are all part of this network, with Google and Microsoft occupying the most central positions within this. What’s more? Microsoft’s node in the network is the bridge connecting the Western and Chinese organizations, a clear sign of its strategic geopolitical role. Microsoft is the only US giant that is well-positioned in China, where it opened its first major R&D campus outside the US in 2010. This presence has also resulted in regular collaborations with major Chinese AI players, from Alibaba and Tencent to leading universities for the development of AI. As it regularly co-authors AI papers with all of them, as well as with many major Western organizations involved in AI R&D (the latter do not frequently co-author papers with Chinese organizations), Microsoft connects the whole AI field, profiting from the research of the most talented scientists and engineers from around the world.

US Big Tech companies also loom large over these conference committees. For instance, every Big Tech organization has at least one member on the organizing committee of NeurIPS, the most coveted machine learning annual conference. Google, which got the largest number of accepted papers in this academic convention in 2022,* had nine of its representatives part of the 39-member committee. The company is also the leading acquirer of AI start-ups, as seen in the case of DeepMind acquired in 2014, which is one of the most significant players in the AI race and has invested heavily in patents. All these signs point to Google profiting from AI, even if it is under stress since Microsoft and OpenAI took the lead in the artificial general intelligence race.

Interestingly, when it comes to AI patenting, the behavior of Big Tech companies varies. While patents seem to be central to Google’s strategy, secrecy is Amazon’s preferred appropriation mechanism, which also explains why it presents less research than the other tech giants in AI conferences.

Unlike Google, Microsoft’s recent strategy has privileged investments in AI start-ups, rather than patents and acquisitions. Often, companies receiving such funding formally remain separate but are ultimately, at least partially, controlled by Microsoft. OpenAI, which developed ChatGPT, provides a testament to this strategy. Microsoft’s first investment in OpenAI at USD 1 billion dates back to 2019. In exchange for funding, Microsoft negotiated an exclusive license to GPT-3. Shortly after Microsoft stepped in, a group of AI researchers left OpenAI due to internal tensions over its research direction and priorities, demonstrating the company’s growing hold over the trajectory of the latter. Crucially, OpenAI depends on Microsoft’s computing power, without which training LLMs would have been impossible. After ChatGPT’s success and almost immediate integration into Microsoft Bing, Microsoft committed an additional USD 10 billion investment in OpenAI. According to interviewees, by early 2023, Microsoft had gone on to own 49% of OpenAI....

....MUCH MORE

Very related, May 9, 2020:

Following up on April's "How to Think About Companies: 'Advantage Flywheels'".

From Eric Jorgenson at Evergreen Business Fortnightly, Aug 7, 2017:

Evergreen is a collection of links to the best learning resources in business, collected by a group of managers, founders, and investors. We contribute resources about one topic, which are synthesized and shared in this Collection. The goal is to learn more efficiently through increased context and focus.Remember, these are designed to feel like short books, you’re meant to meander and spend ~3 hours on this topic. Save these links and read them throughout the week. Immerse yourself in this topic and leave the week smarter than you started it!I admit, I was not completely sure what I was talking about when I chose “Flywheel Effects” as a topic. But that’s part of the fun.This turned into a fascinating adventure through Competitive Advantages, Mental Models, and practical lessons for operators. Also lots of fun pictures and diagrams in this one!Here’s the “Table of Contents”:

- What is the Flywheel Effect?

- Applications of Flywheel Effect (and Meta-Competitive Advantages)

- The Best Examples of Flywheels

- How to Push the Flywheel

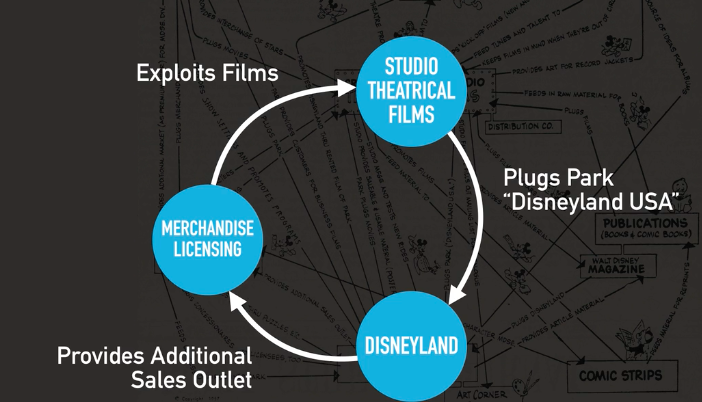

I think we ended up in a good place, but as always I’d love to hear if you think I’m wrong on any of this so I don’t stay quite as ignorant as I am now.What is the Flywheel Effect?Definition…?There doesn’t seem to be a generally agreed-upon definition of the Flywheel Effect. It was used because it was a metaphor to help readers visualize momentum.VisualizationJim Collins originally used the Flywheel as a metaphor in Good To Great:Picture a huge, heavy flywheel — a massive metal disk mounted horizontally on an axle, about 30 feet in diameter, 2 feet thick, and weighing about 5,000 pounds. Now imagine your task is to get the flywheel rotating on the axle as fast and long as possible.Pushing with great effort, you get the flywheel to inch forward, moving almost imperceptibly at first. You keep pushing and, after two or three hours of persistent effort, you get the flywheel to complete one entire turn.DissectionThe Flywheel Effect is used to describe a handful of concepts at once, which are rarely split apart. Here is each component piece I could identify, and how it relates to the Flywheel illustration.Momentum — An object at rest tends to stay at rest, and object in motion tends to continue in motion. Newton’s first law, applied to business. Flywheels (being massive heavy objects) are hard to get moving. If they get moving, they are likely to continue.Feedback Loops — The faster the wheel is spinning, the easier it is to add incremental speed. The faster it moves, the more energy it generates. And the more excited everyone is about how great this Flywheel is!Compounding Return on Effort —No “one push” makes it happen. Continuous small inputs add up into an impressive output, eventually.Direction — Sustained effort must be focused in one direction in order to maintain momentum and compounding returns. Misplaced effort is either wasted or counterproductive.You can see each of these concepts in this one paragraph from Good To Great explaining the effect:The momentum of the thing kicks in your favor, hurling the flywheel forward, turn after turn … whoosh! … its own heavy weight working for you. You’re pushing no harder than during the first rotation, but the flywheel goes faster and faster. Each turn of the flywheel builds upon work done earlier, compounding your investment of effort. A thousand times faster, then ten thousand, then a hundred thousand. The huge heavy disk flies forward, with almost unstoppable momentum.Definition, againThough really this whole post is an attempt to define and understand The Flywheel Effect, it seems like a let-down without a one-sentence explanation. So with all that said… here’s my shot at a definition.Flywheel Effect: Positive feedback loops that build momentum, increasing the payoff of incremental effort.Or, Flywheel Effect in Normal English: When good things you do lead to more good things “just happening”.Applications of The Flywheel EffectIn resources mentioning the Flywheel Effect, it is often conflated with ideas that co-occur, but are distinct concepts. It seems like an easy mistake to make.My current thinking is The Flywheel Effect, as we’ve defined it, is a kind of meta-competitive advantage.It can accelerate the growth of a business and the widening of a moat, but it is not itself a source of competitive advantage. It is a force-multiplier of existing competitive advantages.Let’s see how the Flywheel Effect interacts with Competitive Advantages:Supply-Side Economies of ScaleThe most basic and old-school competitive advantage — the bigger you get, the cheaper you can produce things and the more available your product is. Think Wal-Mart and Carnegie Steel.The bigger these companies got, the cheaper they could sell their goods for, the more leverage over suppliers, and the bigger the brand became.Another example, from Ben Gilbert’s talk (more later) is Disney. As their empire of entertainment grew, the positive feedback loops between their various businesses became stronger:

....MUCH MOREBrandAnother basic Flywheel Effect exists for Brand. To use an oddball example to isolate the effect better — think of College Basketball programs recruiting players.Every time they have a player drafted or win a championship, it becomes a more desirable school for the next round of players, and on it goes. Each win makes the next win slightly easier.Another example, Munger’s explanation of the powers of scale for Coca-cola.Network Effects (Demand-side Economies of Scale)Another advantage of scale comes from psychology. The psychologists use the term social proof. We are all influenced — subconsciously and to some extent consciously — by what we see others do and approve. Therefore, if everybody’s buying something, we think it’s better. We don’t like to be the one guy who’s out of step.The social proof phenomenon which comes right out of psychology gives huge advantages to scale — for example, with very wide distribution, which of course is hard to get. One advantage of Coca-Cola is that it’s available almost everywhere in the world.

Network Effects and Flywheel Effect are very commonly conflated, because they so commonly occur together.....

In ecology and energy and just about any other study of natural systems, positive feedback loops are terrifying.

The same probably goes for business as well, think Amazon's endgame as an example.