LOS

ANGELES—Brian Mainolfi has been drawing since he came to this city in

1994. The Baltimore native started as an assistant to legendary Looney

Tunes animator Chuck Jones, worked on Disney’s “The Hunchback of Notre

Dame” and “Mulan,” and spent a decade on the animated sitcom “American

Dad.”

The appeal of the work was simple. “People love cartoons,” he said. “And I love making cartoons.”

Since

his last show was canceled in 2024, Mainolfi’s artistic output has been

limited to dinosaurs and monsters in his sketchbook. Like thousands of

people who work in the entertainment industry, he has become collateral

damage of a precipitous slowdown in production. The only work he’s found

is teaching an animation class at a Cal State campus three hours away,

for $350 a week.

Mainolfi’s

family of four never lived extravagantly on his salary of around

$100,000, but now they’re using retirement and college savings and

scrimping to survive in their three-bedroom ranch house in suburban

Burbank. With his union healthcare set to disappear at the end of the

year for lack of work, the 54-year-old is trying to figure out for the

first time in his life what he could do to make money besides draw.

“By

the end of the year if I don’t have something, I’m going to have to

apply to a big-box store or a grocery store or something,” he said.

Los

Angeles is full of transplants who moved here to pursue dreams of

working in movies and TV. Few earned millions as stars or A-list

directors. They build the sets, operate the cameras, manage the

schedules and make sure everything looks and sounds perfect. The work

isn’t steady, because film shoots end and TV shows get canceled. But

established professionals had rarely gone more than a few months between

gigs—until now.

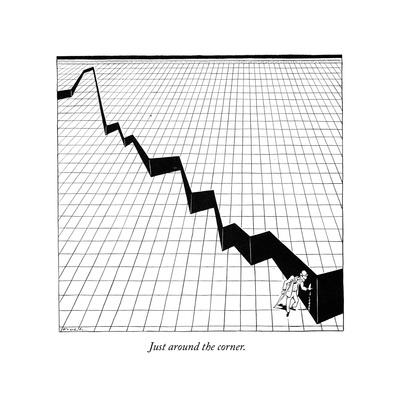

The entertainment industry is in a downward spiral that began when the dual strikes by actors and writers ended

in 2023. Work is evaporating, businesses are closing, longtime

residents are leaving, and the heart of L.A.’s creative middle class is

hanging on by a thread.

“This

is the first year since 1989 that I haven’t had a show to work on,”

said Pixie Wespiser, a 62-year-old production manager and producer who

has worked on 36 TV series, including the original “Night Court” and its

recent revival. “I look around and I see so many people who are

seriously suffering.”

At

the end of 2024, some 100,000 people were employed in the motion

picture industry in Los Angeles County, according to the Bureau of Labor

Statistics. Two years earlier, there were 142,000.

The

primary reason is that Hollywood is making less stuff. The film

business has yet to rebound from the shutdown of theaters during the

pandemic. TV production was booming in the 2010s and early 2020s as

companies tried to jump-start streaming services, but in 2022, investors saw streaming growth was slowing

and decided what actually matters is profitability. Entertainment

companies, which plan productions many months in advance, cut spending

dramatically when the strikes ended the following year.

Nearly

30% fewer movies and TV shows with budgets of at least $40 million

began shooting in the U.S. in 2024 than in 2022, according to data firm

ProdPro. The first three-quarters of this year were down another 13%.

The

situation is particularly dire in Los Angeles. Because of the region’s

high costs and a state production tax credit that, until recently,

lagged behind what competitors like Georgia and British Columbia were

offering, studios make most of their content far from their corporate

offices. Last year, there was less production activity in the Los

Angeles area than at any time since at least 1995, save for the

pandemic, according to the nonprofit group FilmLA.

The

industry’s slump is contributing to L.A.’s broader economic challenges.

The region’s recent employment growth has been anemic compared with

other major metropolitan areas and the nation overall. Its 5.7%

unemployment rate is higher than California’s 5.5% and the nation’s

4.3%. And L.A. is still struggling to recover from the winter’s devastating fires

in Altadena and the Pacific Palisades, where many entertainment workers

lived. That disaster exacerbated the city’s already severe housing

crunch.

Hollywood

has endured downturns before, but rarely this sudden and severe. Some

industry analysts believe consumers might be pivoting permanently from

professionally made content to the endless buffet of YouTube and social media.

Any

rebound in production activity would take at least a few years, and

possibly many more. And a full recovery might never happen if generative

artificial intelligence makes animation and visual-effects jobs

obsolete, as many workers fear.

Meanwhile, thousands of dreams built around working in the movie and TV business are evaporating.

Missing purpose

Thomas Curley won an Oscar recording the sound on 2014’s “Whiplash” and had more job offers than he knew what to do with as recently as 2022. The 49-year-old hasn’t worked since April of last year, save for one week on a movie that was made in Europe but needed to shoot exteriors in San Francisco.The

hardest part isn’t watching his savings wither while he does home

improvement projects and hunts for jobs, Curley said. It’s missing the

creative camaraderie he has enjoyed for most of his adult life on movie

and TV sets.

“Feeling

like you’re part of a team that’s making something that can provide joy

for millions of people around the world is what drew me here in the

first place,” said the native of upstate New York. “That level of

purpose is a really hard thing to let go of.”

Entertainment

industry workers got through last year with a mantra: “Survive ‘til

25.” But jobs are even more scarce this year. L.A. and New York-based

members of the health and pension fund that covers most

behind-the-scenes craftspeople worked 18% fewer hours this year through

mid-August than in the year-earlier period.

“It

felt like the floor fell out,” television writer Matt Walsh said of the

evaporation of job prospects. After moving to L.A. from Orange County,

he spent a decade hustling as an assistant on sets and in writers’ rooms

before finally getting his first scriptwriting assignment in 2023, on

the TBS series “Miracle Workers.”

Since

the strikes ended, the 34-year-old hasn’t been able to find work as a

writer. He’s back to working as a production assistant, the first job he

ever had in entertainment.

Hollywood’s

downturn has rippled through the region’s economy. Fewer productions

mean fewer orders for props, costumes and catering from local

businesses, and less spending by unemployed or anxious workers on

everything.

Courtney

Cowan’s Milk Jar Cookies shop made deliveries to movie sets and agents’

offices, but most of its business was regular people. She was expecting

2023 to be a banner year with the opening of her second location and a

franchise program. Instead, the strikes began and sales immediately

dropped 30%....

Brutal, just brutal.

Possibly also of interest: