Huh.

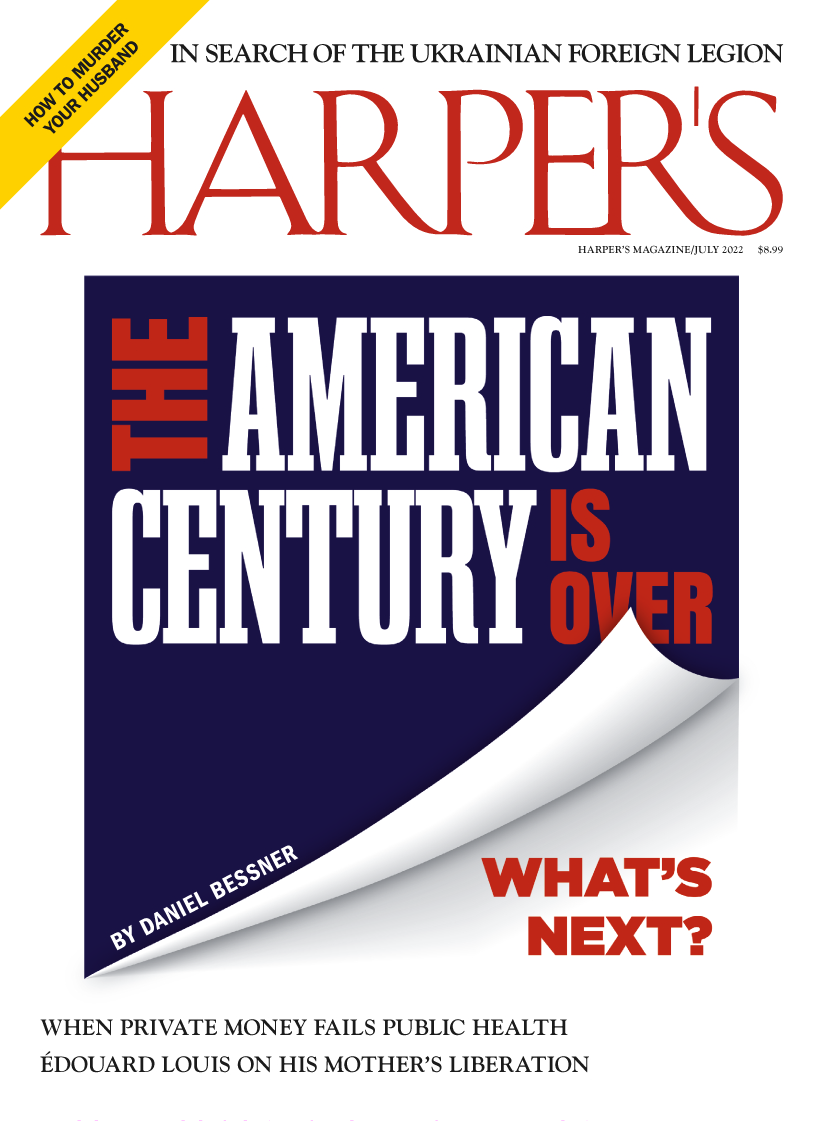

From Harper's:

Empire Burlesque

In February 1941, as Adolf Hitler’s armies prepared to invade the Soviet Union, the Republican oligarch and publisher Henry Luce laid out a vision for global domination in an article titled the american century. World War II, he argued, was the result of the United States’ immature refusal to accept the mantle of world leadership after the British Empire had begun to deteriorate in the wake of World War I. American foolishness, the millionaire claimed, had provided space for Nazi Germany’s rise. The only way to rectify this mistake and prevent future conflict was for the United States to join the Allied effort and

accept wholeheartedly our duty and our opportunity as the most powerful and vital nation in the world and . . . exert upon the world the full impact of our influence, for such purposes as we see fit and by such means as we see fit.

Just as the United States had conquered the American West, the nation would subdue, civilize, and remake international relations.

Ten months after Luce published his essay, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and the United States, which had already been aiding the Allies, officially entered the war. Over the next four years, a broad swath of the foreign policy elite arrived at Luce’s conclusion: the only way to guarantee the world’s safety was for the United States to dominate it. By war’s end, Americans had accepted this righteous duty, of becoming, in Luce’s words, “the powerhouse . . . lifting the life of mankind from the level of the beasts to what the Psalmist called a little lower than the angels.” The American Century had arrived.

In the decades that followed, the United States implemented a grand strategy that the historian Stephen Wertheim has fittingly termed “armed primacy.” According to the strategy’s noble advocates, human flourishing, international order, and the future of liberal democratic capitalism depended on the nation spreading its tentacles across the world. Whereas the United States had been wary of embroiling itself in extra-hemispheric affairs prior to the twentieth century, Old Glory could now increasingly be seen flying across the globe. To facilitate their crusade, Americans constructed what the historian Daniel Immerwahr has dubbed a “pointillist empire.” While most empires traditionally relied on the seizure and occupation of vast territories, the United States built military bases around the world to project its power. From these outposts, it launched wars that killed millions, protected a capitalist system that benefited the wealthy, and threatened any power—democratic or otherwise—that had the temerity to disagree with it.

As Luce desired, by the end of the twentieth century, the United States, a nation founded after one of the first modern anticolonial revolutions, had become a world-spanning empire. The “city on a hill” had evolved into a fortified metropolis.

But in the past six years, two transformational events have begun to reshape the United States’ place in the world. First, the election of Donald Trump suggested to domestic and foreign audiences alike that the country might not be forever beholden to the idea that global “leadership” was a vital American interest. Instead of proclaiming the inviolability of the vaunted “liberal international order,” Trump approached international relations as any corrupt businessman would: he tried to get the most while giving the least. He thus withdrew from several international organizations and agreements—including the World Health Organization, the Paris climate agreement, the Iran nuclear deal, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, and the Open Skies Treaty—and initiated trade wars intended to boost American business. Taken with his bellicose rhetoric, these actions demonstrated that the world could no longer assume that the United States was committed to defending the geopolitical status quo.

Second, the emergence of China as an economic and military powerhouse has decisively ended the “unipolar moment” of the Nineties and Aughts. The country only recently referred to as a “rising tiger” (Orientalism never dies) now boasts, according to some measures, the largest military and economy on earth. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank offer alternatives to the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and other Western-dominated institutions, which, to put it mildly, aren’t exactly beloved in the Global South.

For the first time since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States confronts a nation whose model—a blend of state capitalism and Communist Party discipline—presents a genuine challenge to liberal democratic capitalism, which seems increasingly incapable of addressing the many crises that beset it. China’s rise, and the glimmers of the alternative world that might accompany it, make clear that Luce’s American Century is in its final days. It’s not obvious, however, what comes next. Are we doomed to witness the return of great power rivalry, in which the United States and China vie for influence? Or will the decline of U.S. power produce novel forms of international collaboration?

In these waning days of the American Century, Washington’s foreign policy establishment—the think tanks that define the limits of the possible—has splintered into two warring camps. Defending the status quo are the liberal internationalists, who insist that the United States should retain its position of global armed primacy. Against them stand the restrainers, who urge a fundamental rethinking of the U.S. approach to foreign policy, away from militarism and toward peaceful forms of international engagement. The outcome of this debate will determine whether the United States remains committed to an atavistic foreign policy ill-suited to the twenty-first century, or whether the nation will take seriously the disasters of the past decades, abandon the hubris that has caused so much suffering worldwide, and, finally, embrace a grand strategy of restraint....

....MUCH MORE