For a certain population subset, socioeconomic status in the United States is harder to change now than at any point in recent history, according to research from the University of Pennsylvania, Princeton University, and elsewhere.

In the first long-term assessment of social mobility in the U.S., Penn sociologist Xi Song and colleagues discovered that mobility has substantially declined during the past 150 years, particularly for those born in the 1940s and later. They also found that the well-documented rise in economic inequality of the past four decades has not affected intergenerational mobility in the ways many expected it would.

The team, which also included researchers from the University of Nebraska Omaha, Northwestern University, and the U.S. Census Bureau, published their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"Most work in this area has focused on more recent decades," says Song, an associate professor in the Department of Sociology at Penn and the lead study author. "Ours looks back to 1850, before the Civil War, and covers two World Wars, the Depression, and social changes in the racial history of the United States."

Song and her collaborators could go that far back thanks to newly available Census data. They examined information from approximately five million people, using first and last names, ages, birthplaces, and parents' birthplaces as identifiers, and then Social Security numbers in the 1940s.

For consistency, the analysis included mostly white males, with a small number of males from other racial groups. In the mid-1800s, most females didn't have jobs outside the home—the gauge the researchers used to measure socioeconomic status—or they changed their names after marriage, making them harder to track over time. Other races were underrepresented due to a low rate of linking across years in the dataset.Possibly related from Noah Smith at Bloomberg last August:

The researchers' analysis showed that for the study population, sons born before 1900 experienced significant upward mobility compared to their fathers. Around that time, the country was moving from agriculture to industry, and with that shift, sons stopped doing the farming their fathers had, taking manufacturing jobs instead. "Many of them migrated from farms to booming towns and cities to become operative workers, blacksmiths, bricklayers, truck drivers, and sales workers, so they achieved a higher socioeconomic status compared to their parents," says Song....MORE

It's Gotten Too Hard to Strike It Rich in America

In a free-market economy everyone is supposed to have the chance to get rich. The dream of making it big motivates people to take risks, start businesses, stay in school and work hard. Unfortunately, in the U.S., that dream seems to be dying.

There are still plenty of rich people in the U.S., and their wealth is increasing. But people outside that top echelon are having a tougher time breaking in. A 2017 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland found that the probability that a household outside the top 10% made it into the highest tier within 10 years was twice as high during 1984-1994 as it was during 2003-2013.

There surely are many reasons for this trend, but one of them probably is the winner-take-all structure of the U.S. economy, where a few people get fabulously lucky with their hedge fund or tech startup, while most people fail.

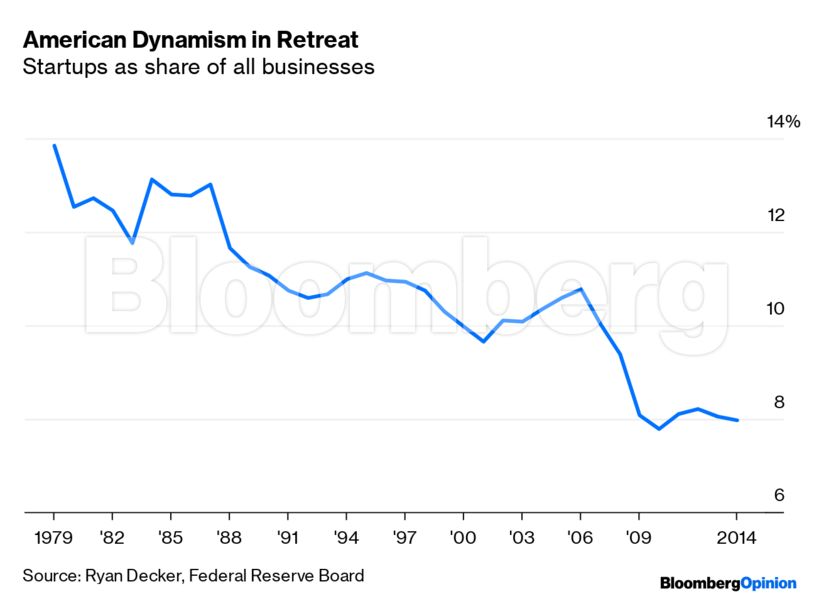

The traditional way to get rich in America is to start a business. For those of modest means, perhaps this would be a corner store or a restaurant; for the more ambitious, a technology startup. Many Americans still do this, but the number is dropping as business formation dries up:

Much of the decline is due to efficient national retail chains muscling out small local businesses. But high-growth startups are on the wane as well, and the dominance of a few giant tech companies may be making it harder for upstarts to reach the loftiest heights of success........MUCH MORE