From Evergreen Gavekal, November 30:

...The pain before the gain.

Because I’ve been in the investment business longer than a lot of EVA readers have been alive, I can personally attest that bull markets are much more fun than bear markets. On that point, this bull has been stomping for so long that many financial professionals have never seen a deep and lasting bear market. Recently, I met with a bright young broker from one of the leading Wall Street firms who has been “in the business” for 5 ½ years. He was shrewd enough to admit he had no idea what it would be like to live through a serious market decline, and he was also wise enough to realize he would have to—possibly sooner than later.

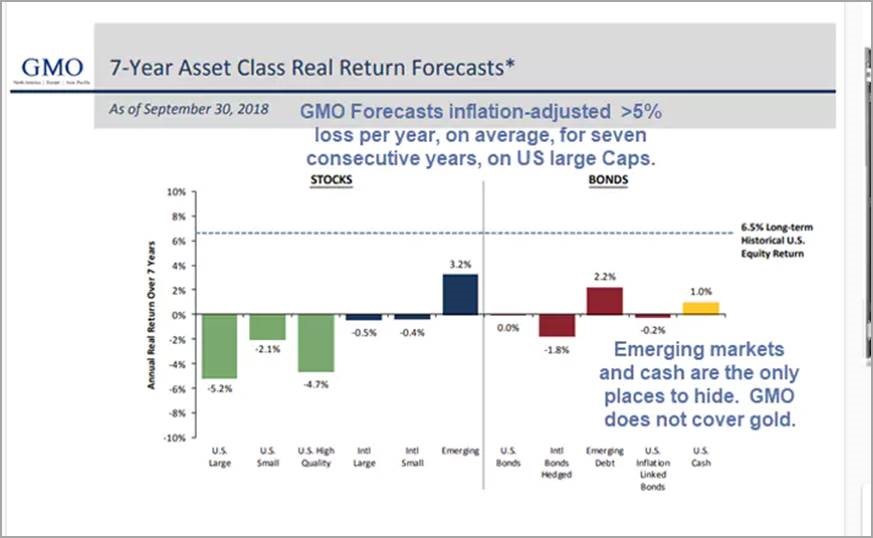

Previous EVAs have often cited the long-term return forecasts by the Boston-based money management giant, GMO. As the S&P has steadily risen from undervalued back in 2009 to fairly valued by 2012 to overvalued by 2014 to extraordinarily pricey by the summer of this year, GMO has methodically lowered their return expectations over the next seven years. The reason you should care about what GMO has to say on this subject is because they have one of the finest forecasting records in, once again, “the business”.

Per the below chart, their forecast through 2025 is rather sobering reading. Even though these are real, or after-inflation, numbers the implications, if they’re right, are enormous. This is particularly true for the tens of millions of Baby Boomers who need to live on the fruits of their portfolios.

Source: GMO as of 9/30/2018

As you can see, what they are projecting is anything but fruitful. Essentially, with a 50/50 mix of US stocks and bonds, GMO is looking for around a 2 ½% average annual negative return, inclusive of inflation.

One of Warren Buffett’s classic adages, “Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful” is predicated upon a crucial and rather obvious notion: you need to have cash on-hand to capitalize on others’ fears. But often, people become too complacent during boom times and allow their capital to remain in investment sectors, areas, or asset classes that are way beyond their sell-by date. Moreover, there is a strong and highly destructive tendency to move funds from underperforming vehicles into the hottest areas which then sets the stage for actual losses once the sky-rocketing sector, style, or stock inevitably succumbs to the laws of gravity.

If there is a devil-like being at work in the financial world, one of his nastiest tricks is making the most dangerous (i.e., grossly over-priced) asset classes look irresistibly attractive. Often, these slices of the investment universe have been generating outrageous returns for several years. The action in tech stocks back in the late 1990s was a graphic, though long ago, example of this. More recently, it has been the relentless rise in the S&P 500, with nary a single down year for nearly a decade. (As I write these words, in late November of 2018, this streak is in jeopardy. However, there’s still a good chance we will see ten consecutive up-years in the US stock market for the first time in recorded history—going all the way back to when shares were traded under a Buttonwood tree in New York shortly after the Revolutionary War.)

Bull markets, especially when they are particularly powerful and/or long-lasting, create a situation where investors become afraid to sell. We humans have been programmed over the eons to pursue activities which provide an immediate reward and avoid those that produce near-term pain or disappointment. That reality has helped us survive endless adversities (why it is we keep voting for our feckless politicians would seem to be an exception to this rule). It goes against every helix of our DNA to pull out of an activity that’s earning money even when wisenheimers like this author trot out a copious collection of charts and graphs to show that the S&P 500 circa late 2018 is dangerously inflated.

Thus, in a way, late-stage bull markets become like an elaborate con job. Perhaps some older readers of this newsletter might recall the entertaining film from the early 1970s, starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford, “The Sting”. Messrs. Newman and Redford played thoroughly likeable con men who came up with an elaborate scheme to bilk a rich crime boss, played by Robert Shaw. The key to making their ploy work was to let their mark win. Once he banked a bunch of easy money, he was ripe for the plucking.

And so it goes with investors. When we’re sitting on years and years of double-digit gains, we become convinced that: A) the market is safe and B) the high returns will continue. As I’ve written before, in these situations investors act as though the lavish profits they’ve “earned” in recent years are somehow securely in the bank. They lose sight of the historical fact that returns during late-stage bull markets are about as lasting as a politician’s campaign promises. In reality, those gains tend to be wiped away almost overnight and the more inflated the market has become, the more years of “in the bank” gains are suddenly repossessed.

Frankly, most of the foregoing has fallen on deaf ears—until recently, that is, starting in early October to be specific. While no one could rightfully call what happened in October of this year a crash, or even a crashette, it nonetheless has catalyzed some serious repricing of risk. Additionally, it got me once again thinking back to another October, 31 years ago.

Flash crash flashback.

As noted in earlier Bubble 3.0 chapters, the 1987 crash was the first time that computers played a starring role in a major market collapse. Since then, of course, we’ve seen a number of those computer-driven cliff dives, although they’ve been limited to, thus far, the “flash crash” variety. These now-you-see-them, now-you-don’t panics happened in 2010, 2011, and 2015. In the latter instance, during August of that year, one ironically classified “low-volatility” ETF plunged 43% in less than an hour!!!

Today, as we all know, or at least we should, computer- or algorithm-based trading is dominant to a far greater degree than it was in 1987. Estimates are that these now represent 80% to 90% of New York Stock Exchange volumes. What is less well understood is that these systems generally don’t try to anticipate the future, as financial markets typically have in the past.

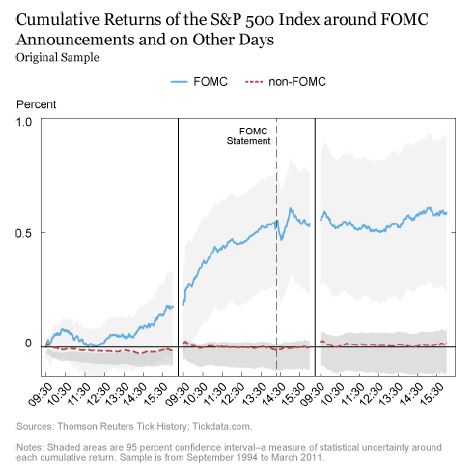

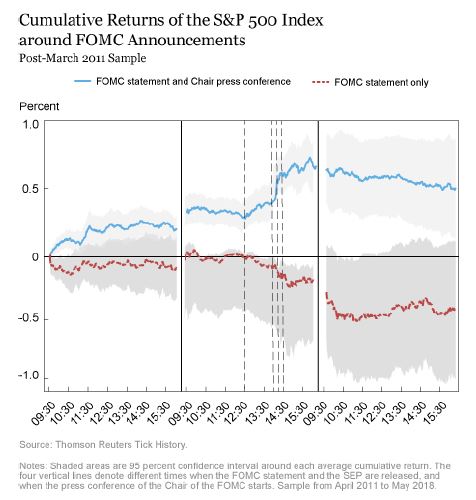

For example, if certain words in Fed press releases have led to market rallies, the same relationship is projected by the machines to happen again. One fascinating factoid in this regard is how much more the market has risen, like 80% of all returns, on Fed press conference days—even if those brought rate hikes—than it has the rest of the time. But don’t ask me to explain why. My only insight is that it simply shows that perhaps the only force driving the stock market these days that is more powerful than the “algos” and computers is the Fed.

Source: Liberty Street Economics as of 11/26/2018

This is definitely not how markets formerly behaved. As the celebrated economist Paul Samuelson once quipped, the stock market at one time had discounted nine of the last five recessions. In my opinion, the enormity of this shift has not been even close to fully appreciated. Most investors, in my view, continue to believe the market’s discounting mechanism is largely unchanged. Yet, as my astute partner Louis Gave--founder of the acclaimed institutional research firm Gavekal---has repeatedly pointed out, this is decidedly not the case. Rather than a market driven by myriad individuals spending endless hours analyzing economic, corporate, and geopolitical information, most of the movements these days are caused by the way in which computers react to current news events. This is not to say research isn’t still conducted but rather that it is overwhelmed by computerized-trading and, of course, passive investing.

It’s common knowledge that the active investing community has been losing hundreds of billions, if not trillions, to its passive counterparts over the past two decades. The chart below makes that abundantly clear, courtesy of Ned Davis, founder of his eponymous firm....MORE