From the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's Liberty Street Economics blog:

Bank Street in New York City is a quaint little six-block stretch in Greenwich Village (see this 48-second video) with a huge cultural legacy—but

no banks. Many cities and towns have a Bank Street and often the street

is so named because that's where most of the banks were originally

located. (It is not likely that any Bank Street got its name

because of its proximity to a riverbank.) However, New York City’s Bank

Street is not where the banks were originally located and it's not even

in the financial district—it's in Greenwich Village. Why, then, is it

called “Bank Street?”

Okay, we cheated in that last paragraph. Manhattan’s banks were not on Bank Street originally

but they were indeed there at some point—they moved northward from Wall

Street in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in an

effort to escape yellow fever. A post

on the Forgotten New York website explains how there were two main

waves of the epidemic in the city and that Bank Street was essentially

named for the first bank to relocate, not the set of banks that

eventually moved there:

Though most neighboring streets are named for local personalities in

the Village’s early days (one early burgess, Charles Christopher Amos,

had three streets named for him), Bank Street is named for one of the

oldest institutions in NYC, the Bank of New York, which opened an office

“uptown” after a yellow fever epidemic downtown on Wall Street in 1798

prompted a relocation. Several other banks followed suit in 1822 after a

second outbreak.

One can view this relocation of banks as an early form of corporate contingency (or business continuity)

planning. Think about how important continuity is in banking and how

advantageous it would have been to keep those early New York banks

functioning. In his 1922 book A Century of Banking in New York, 1822-1922, author Henry Lanier describes, in the chapter “The Year the Banks Migrated,” the Bank of New York’s forethought:

Some bankers and others had been more foresighted. As noted, one of the

first deaths in the scourge of 1798 was a book-keeper in the Bank of

New York. "Fearing another visitation of the pestilence, the bank made

arrangements with the branch Bank of the United States to purchase two

plots of eight city lots each, in Greenwich Village, far away from the

city proper, to which they could remove in case of being placed in

danger of quarantine. Here two houses were erected in the spring of

1799, and here the banks were removed in September of that year, giving

their name, Bank Street, to the little village lane that had been

nameless before. The last removal was made in 1822, when the yellow

fever raged with unusual virulence, and the plot which had been

purchased for $500 was sold in 1843 for $30,000."

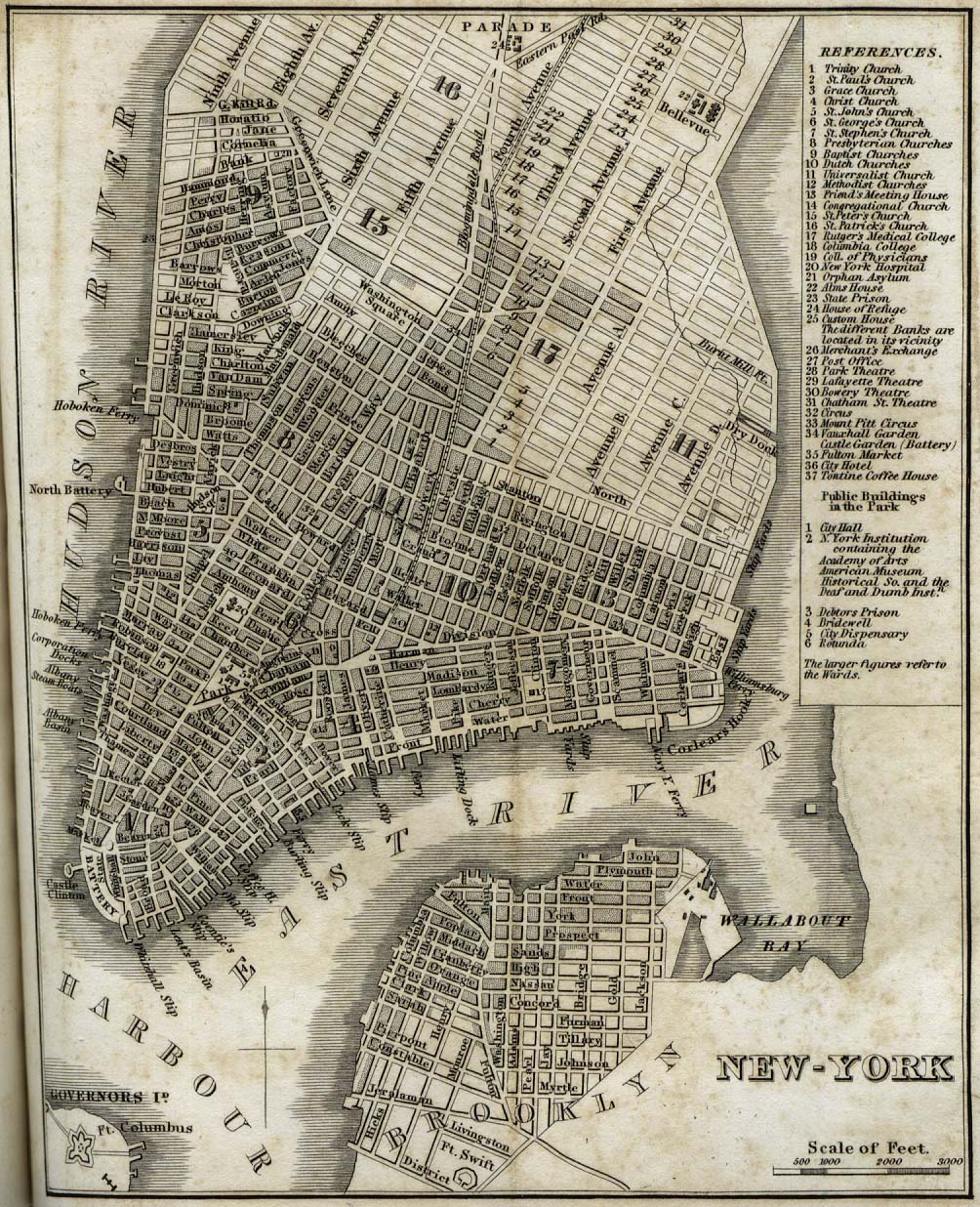

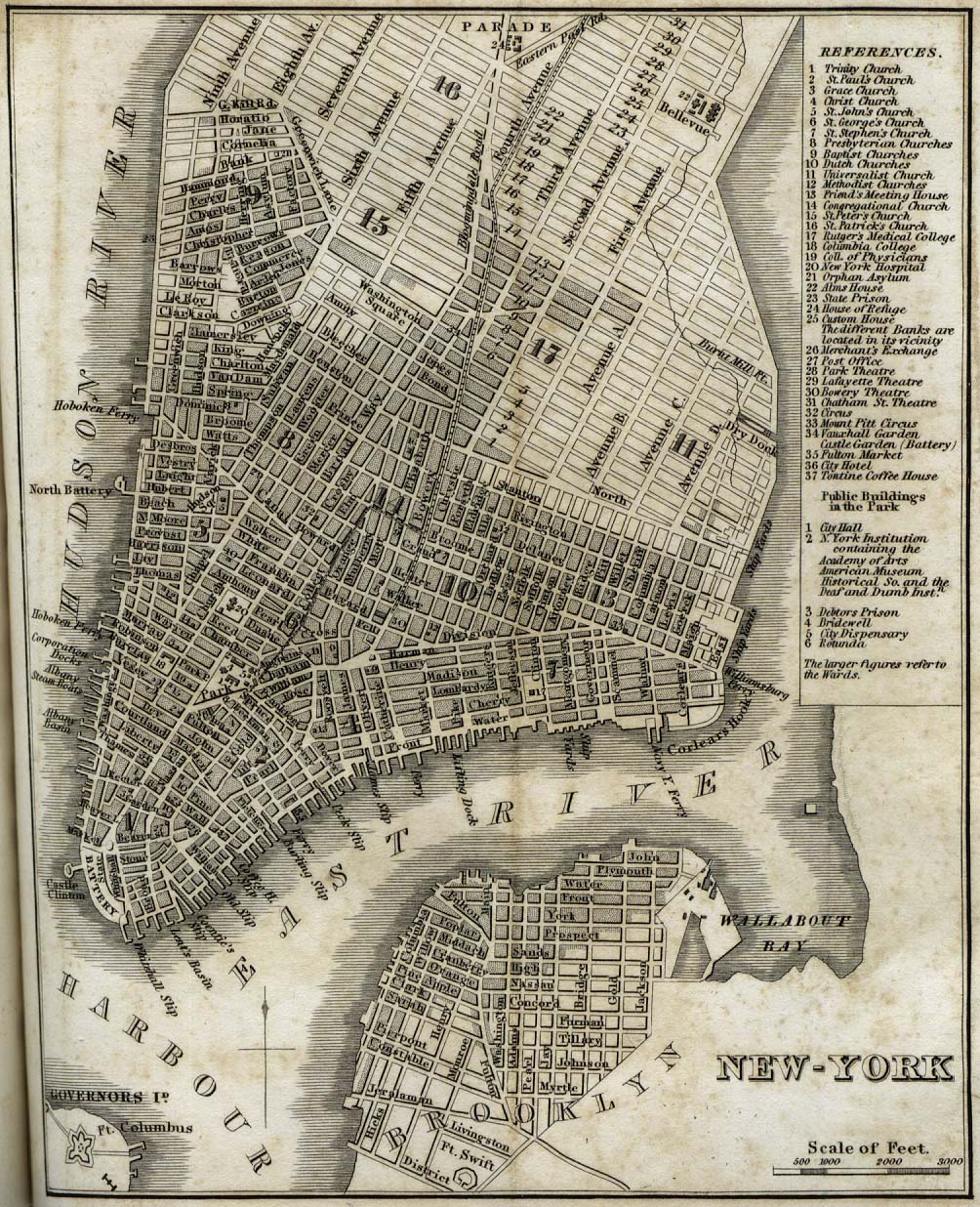

In this 1842 map of lower Manhattan, you can see Bank Street just to the right of the large “E” of the “Hudson River” label. (Here is a 1933 street view.)

Of course, Wall Street is in the bottom tip of the island. Bank Street

is about 2.7 miles north of Wall Street. Yes, it takes a bit of time to

walk from one to the other—but not that long. How did they know that

this distance would be sufficient to prevent the fever’s spread? They

didn’t know with scientific certainty, but they had an idea (see below),

and the move was indeed sufficient. Scientists at the time were

ignorant of the mechanism of transmission—the mosquito. That discovery and proof thereof did not come until 1900 (see video from PBS’s American Experience

series, which describes the horror of this disease and how three

medical scientists discovered the virus’s means of transmission).

Mosquitoes don’t travel very far by themselves (most don’t travel more than a mile

from where they hatched), so for yellow fever to have spread to Bank

Street, someone would have had to transport an infected mosquito and let

it loose among people on Bank Street, or an infected person would have

had to hang around in the Bank Street neighborhood long enough to be

bitten by a mosquito, of which there were possibly a lot fewer in the

Village. The question of why mosquitos could not have been blown by the

wind from one location to the other is posed

by Henry Lanier in the same book mentioned above. (Lanier also somewhat

answers the question about why people thought the move north would be

sufficient):

Now, it happened that there was at the city’s very door a safe refuge.

From the time of the “epidemical distemper or plague” reported by Mayor

John Cruger in 1742, New Yorkers had discovered they could escape the

infection by fleeing to the village of Greenwich, only two or three

miles away. This haven was considered almost proof even against smallpox

. . .

...

MORE