A half-dozen sites/blogs decided the thing to do was link to Mr. Catherwood.

So we waited until this weekend and changed the piece to which we intended to link.

Enjoy.

Jamie Catherwood, The Finance History Guy, via Medium:

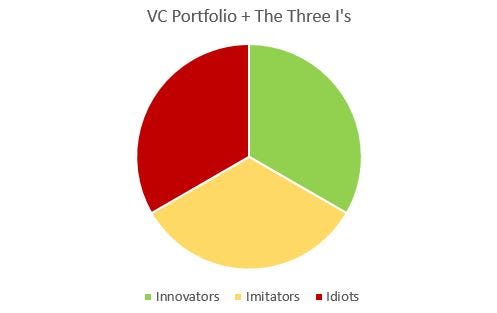

“First come the innovators, who see opportunities that others don’t. Then come the imitators, who copy what the innovators have done. And then come the idiots, whose avarice undoes the very innovations they are trying to use to get rich.”— Warren Buffet

A great deal of investing comes down to a process of identifying innovators, scrutinizing imitators, and screening out idiots.This principle is applicable to everything from stock-picking to assessing management teams. Nowhere, however, is the concept more prevalent than in venture capital.Every day, VC firms in Silicon Valley and beyond are inundated with pitches from startups touting innovative products and groundbreaking technology. Therefore, the clear determinant of a VC firm’s success lies in their ability to locate genius in a sea of mediocrity.The obvious difficulty of this endeavor is reflected in the breakdown of a VC firm’s expected returns. As industry veteran Fred Wilson summarized it:“I’ve said many times on this blog that our target batting average is ‘1/3, 1/3, 1/3’, which means that we expect to lose our entire investment on 1/3 of our investments, we expect to get our money back (or maybe make a small return) on 1/3 of our investments, and we expect to generate the bulk of our returns on 1/3 of our investments.” — Fred WilsonTo put it much more crudely:

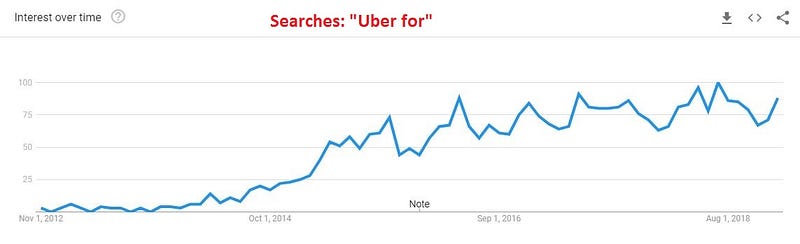

An already difficult process then becomes even harder after the wild success of a truly innovative company. For example, Uber’s dominance prompted an outbreak of “Uber for X” startups.

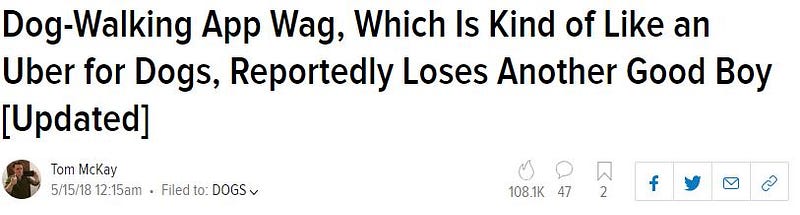

From a behavioral standpoint, it’s not easy for an investor to resist companies claiming to be the ‘Uber for X’ after witnessing Uber’s success.To be clear, there have been successful imitators. Wag!, the “Uber for Dogs”, being a prime example.

However, for every imitator like Wag! and Lyft, there is a longer list of failed imitators. Cherry, for instance, was the “Uber for carwashes” that eventually closed up shop.That said, even the successful imitators aren’t perfect… poor Fluffy.

During the late 17th century, London’s nascent stock market experienced a wave of innovation. In 1687, only 15 public companies were listed on the London Stock Exchange. By 1695, however, that figure had increased tenfold.

The impetus for this investment boom is partially due to the Nine Years War, which restricted overseas trade with foreign powers. British investors were forced to deploy their capital into domestic investments as a result.“A great many stocks have arisen since this war with France; for trade being obstructed at sea, few that have money were willing it should lie idle, and a great many that wanted employment studied how to dispose of their money…which they found they could more easily do in joint-stocks, than in laying out the same in lands, houses or commodities…” — John Houghton (1694)What truly kick-started this period of speculation and startup investments, however, was a successful treasure hunt.

The Innovator“Thanks be to God! We are all made!”— Sir William Phips (1687)Sir William Phips was described by his contemporary, Daniel Defoe, as someone who “sought wealth and advancement through money-making schemes financed by others”.A trader and seafarer by nature, Phips commanded boats making frequent trips to the West Indies. In the course of these journeys, Phips heard rumors of a sunken ship in the Caribbean , the Concepción, which held unimaginable treasures.

Though many would scoff at such gossip today, the rumors were not unfounded. The Spanish had transported scores of precious metals from Mexico for over a century, and many of these ships did not make it home.

Before long, Sir Phips decided to try his luck at locating the Concepción. Just as the modern founder ventures to Silicon Valley in search of funding on Sand Hill Road, Sir Phips returned to London in search of an investor.

Phips found his 17th century venture capitalist in the Duke of Albemarle, and his syndicate of investors. The group of financiers quickly formed a small joint-stock company for funding the expedition. This joint-stock company could be considered a VC firm equivalent.

This was truly ad-venture capital.......MUCH MORE