Ryan Holiday

When Houghton Mifflin published ‘Mein Kampf’ in 1933, it sparked what could be the strangest saga in publishing history

There are horror stories about what can go wrong on release day, and then there is the story of John Fante. There has always been a rich genre of heartbreaking tales of what could have been — from albums released on September 11th to sculptures destroyed in transit — and then there is the novel Ask the Dust, a book whose tragic bad luck is spoken of in hushed tones — passed from writer to writer and repeated endlessly by critics and journalists — as the ultimate publishing nightmare.

The fact that a brilliant work would not be appreciated in its time is not, in and of itself, a remarkable event. But the nearly unbelievable (and up until now, largely unconfirmed) how of Ask the Dust, now widely considered to be a sort of West Coast Gatsby — which was released to rave reviews in 1939 but did not begin to find its audience until the early 1980s as Fante, then a double amputee, lay dying of diabetes — was not some inexplicable, unavoidable force majeure. It was not ill-health or racism or hubris. It was something much more specific. It was something with a face and a name. Really just one name, in fact.

While the list of artists victimized by the Nazis is long — from Stefan Zweig to Felix Nussbaum — few of them were first-generation Italian immigrants living and writing books in sunny Southern California. Very few of those tragedies were rendered through a decision by a U.S. Federal Court. And of course, none of them were ultimately redeemed by a chance encounter on the shelves of the Los Angeles Public Library nearly a half-century later.

What follows, then, is one of strangest sagas in all of publishing — perhaps in all of art. It is a story of greed and stupidity, of bad timing and eventual vindication. Ultimately, it’s the story of how some of the “finest fiction ever written in America” managed to triumph over undeniable evil. And it’s one that deserves the consideration of every creator, every publisher, every copyright attorney, and, as it looms ever larger, of anyone involved in the debate of what it means to #NoPlatform offensive and hateful speech.

The Truth Is Always Stranger Than FictionIt does not seem that Houghton Mifflin — which had been a publishing powerhouse since the late 1800s — ever considered not publishing the dictated prison memoirs of the rising Austrian politician. Adolf Hitler had published Mein Kampf — a shortened version of its original title, Viereinhalb Jahre (des Kampfes) gegen Lüge, Dummheit und Feigheit (or, “A Four and One-Half Year Struggle Against Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice”) — in 1925, in part to pay off his legal fees and fund his political ambitions. It was a steady seller in Germany as his political fortunes rose, increasingly becoming a book of international interest.

After seeking approval from its board, Houghton Mifflin’s editors set out to acquire Mein Kampf just two months after the Reichstag fire gave Hitler the pretext for dictatorial powers in Germany. The company, with its history of snagging lucrative exclusives on overseas political books, was the perfect partner for Eher-Verlag, the publishing house controlled by Hitler in Germany. The two houses, one in Boston, one in Munich, quickly reached an agreement for an exclusive license which, at the then-standard royalty rate of 15 percent, would have paid Hitler roughly 50 cents per copy. The publication announcement for My Battle, (as Houghton Mifflin titled their first edition of Mein Kampf) on July 13, 1933 exhibits Houghton Mifflin director Roger Scaife’s flair for publicity and hyperbole:For the first time the German Dictator speaks to the American people. In the form of an autobiography, he tells the stirring story of the growth of an idea from the beginnings to the proportions of a great national movement and his own meteoric rise…To publish an author who had already begun to push the world to the brink of war was controversial, even in the mid-1930s. So too was Houghton Mifflin’s decision to publish a version of Mein Kampf which omitted some of Hitler’s darkest rants about Jews, edits made by Nazi agents who hoped the abridged edition would make his views more palatable overseas.

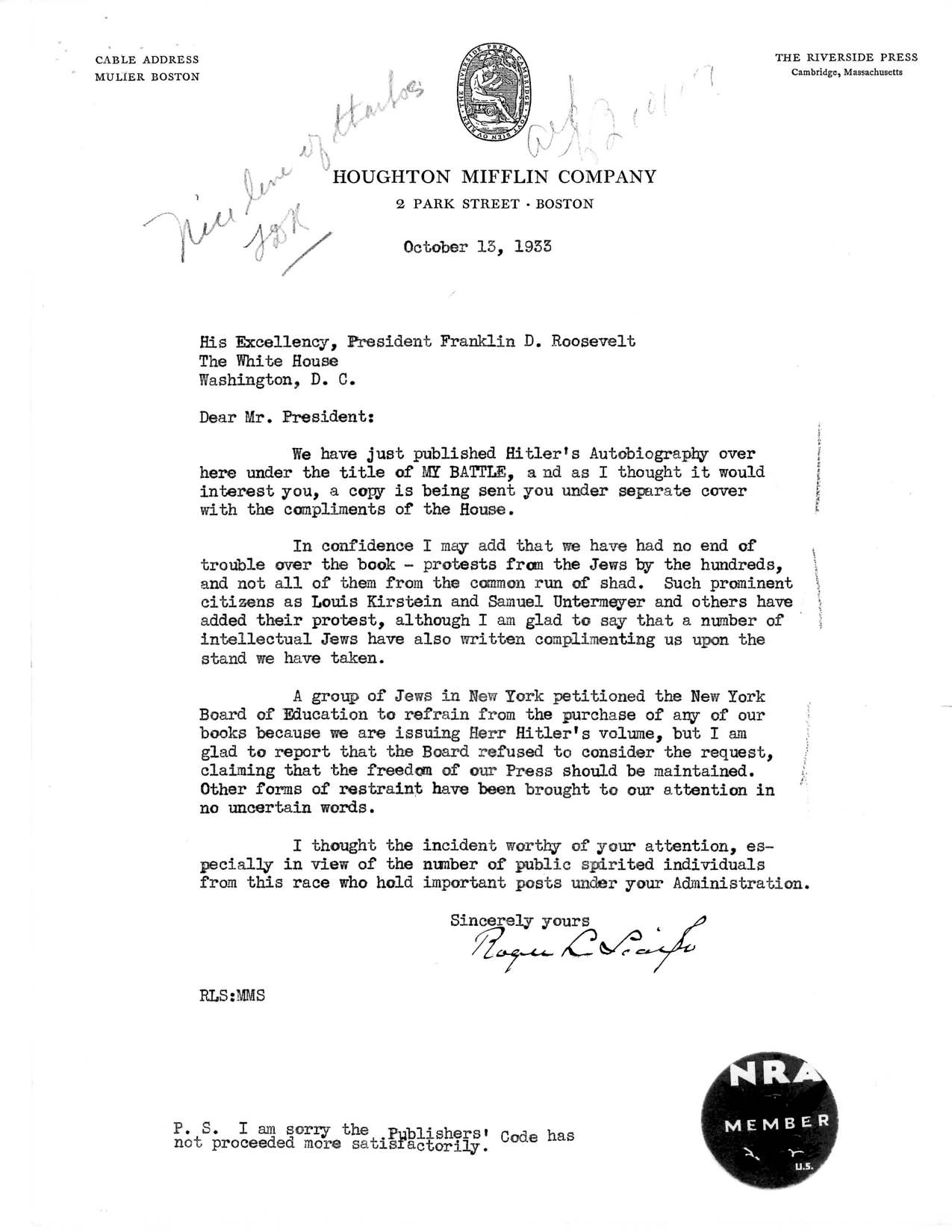

What explains this? It’s only slightly uncharitable to suggest there may have been ideological sympathies between Hitler and the leadership at Houghton Mifflin at the time. The advance copy Roger Scaife sent to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt included a note, apprising him of recent objections from New York City schools of Houghton Mifflin-published textbooks:In confidence I may add that we have had no end of trouble over the book — protests from the Jews by the hundreds, and not all of them from the common run of shad…. although I am glad to say that a number of intellectual Jews have also written complimenting us upon the stand we have taken.

Photo via Ryan Clark Holiday

This was important for FDR to know, Scaife concluded, due to the “number of… individuals from this race who hold important posts under your Administration.” In a note that accompanied a complimentary copy of the book, Roger explained to Hitler in October 1933 that, despite strong opposition, Houghton Mifflin had “nevertheless, persisted in our plans, and we believe that the actual publication of the book will result in wide discussion and, we hope, in satisfactory sale.” FDR, who had also read the book in its original German, took the time to write inside his pre-publication copy of My Battle, “this translation is so expurgated as to give a wholly false view of what Hitler is or says.”

The truth was, most Americans had interests outside of German politics in 1933 — namely the Great Depression, which was then in its fifth year. There would eventually be enough Nazis in New York City to fill Madison Square Garden — which they did, for the now infamous German American Bund Rally in 1939. But in 1933, Mein Kampf had sold just 4,633 copies in the U.S. (compared to worldwide sales of roughly 1 million copies, mostly in Germany, since publication). By 1937, sales had slowed to 1,723 copies in the U.S. (Meanwhile, newlyweds and soldiers in Germany were given free copies at the expense of the state. The German government also forgave Hitler’s tax debt on the copies he’d sold before taking office.)

In the fall of 1938, as appeasement reigned in Europe and the Munich Agreement gave Hitler the concessions needed to annex Czechoslovakia, American interest in his book began to spike. Between September and October of 1938, Mein Kampf sold more copies alone than it had in all of 1934. In the end, American sales in 1938 eclipsed all the previous years combined. Hitler had already sold millions of copies in Germany, but now he was a bestseller in the free world.

It wasn’t simply his overseas exploits driving sales. Houghton Mifflin moved aggressively to market the book, improving accessibility and price with a more mass-market edition. The new edition included a blurb from Dorothy Thompson, an American journalist who had been expelled from Nazi Germany. “As a liberal and democrat I deprecate every idea in this book,” she wrote. “The reading of this book is a duty for all who would understand the fantastic era in which we live, and particularly it is the duty of all who cherish freedom, democracy and the liberal spirit. Let us know what it is that challenges our civilization.”

Initially, Hitler’s representatives were not pleased with the branding changes, and demanded an explanation and improvements. The managing editor for Houghton Mifflin attempted to placate their German business partners in a letter, explaining the publisher’s logic. “The sales of the book in the original printing had not been up to our expectations, and we believed that a new promotion effort, of which this jacket is an important part, was desirable in order to secure for the book the distribution that its importance unquestionably deserved,” Ira Rich Kent wrote to Arthur Teele, the lawyer for the German consulate in Boston, in March of 1937. He turned out to be right, and the increased sales — some 14,000 in 1938 — flattered Hitler’s vanity enough to satisfy him.

Perhaps by then, the book had already served his plans for world domination and was no longer a priority. Perhaps he was too busy and rich to care, having earned millions from sales at home and across Europe. In the years since Houghton Mifflin first published Hitler in the U.S. in 1933, he had gone from the legitimately elected German chancellor to, after the Reichstag fire, dictator. A year later, the Night of the Long Knives purged the country of most of his political enemies. In 1935, the Nuremberg Laws excluded Jews from citizenship. By 1937 and 1938, Hitler’s designs on Austria were in the air.....MUCH MORE

Wrong Place, Wrong Time

In 1938, John Fante, an ambitious 29-year-old son of an Italian immigrant — whose writing had kept him only a meal or two from starvation up until that point — published his first book, Wait Until Spring, Bandini, with publishers Stackpole and Sons.,,,