Here are some related ideas from Building the Skyline, February 5:

Book Review: Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities by Alain Bertaud. The MIT Press, 2018

Today, just over half of the world’s population lives in cities. By the middle of the 21st century this figure will likely be near 75%. The future is decidedly urban. Those who care about the well-being of humanity must naturally be concerned with how cities work; for when they function well, people are happier and healthier (and other species as well).

The Dream of Urban Utopia

At least since the early days of the Industrial Revolution, when the skies were black with coal dust, and poor factory workers huddled together in squalid housing, city planners and utopians dreamt of manufacturing the well-ordered city. They envisioned a place where each worker has access to clean air, open space, and roads laid out in a rational manner. They advocated for better living through planning—the imposition of top-down solutions to urban problems.

At the national level, the planning of entire economies has come and gone. Experiments with socialism in the Soviet Union and China, for example, have ended in failure. Yet, the urge to impose plans and rules on cities remains strong—an urge deeply rooted in the DNA of local government, be it through zoning, strict building regulations, or detailed glossy planning documents that seek to dictate the future city form.

Order without Design

But those who study the economics of cities remain skeptical that order can be imposed from above. As Alain Bertaud argues in his masterful book, Order without Design, it doesn’t work for nations, and it doesn’t work cities. But, to this day, the planners of the world just don’t trust the marketplace. They observe disorder and conclude it must be bad. Bertaud sees otherwise. The market does create order, but only if we let it.[1]

For over a half-century, Bertaud was a city planner. His first job, in 1965, was as an “Urban Inspector,” charged with issuing (or denying) housing permits in Tlemcen, Algeria. Over the years, he rose to the position of Principal Urban Planner at the World Bank. Throughout his long career he has helped plan or consult on numerous projects in cities of all stripes and sizes from those in socialist Russia and China to Haiti and India. He has observed much about the way cities work, or not.

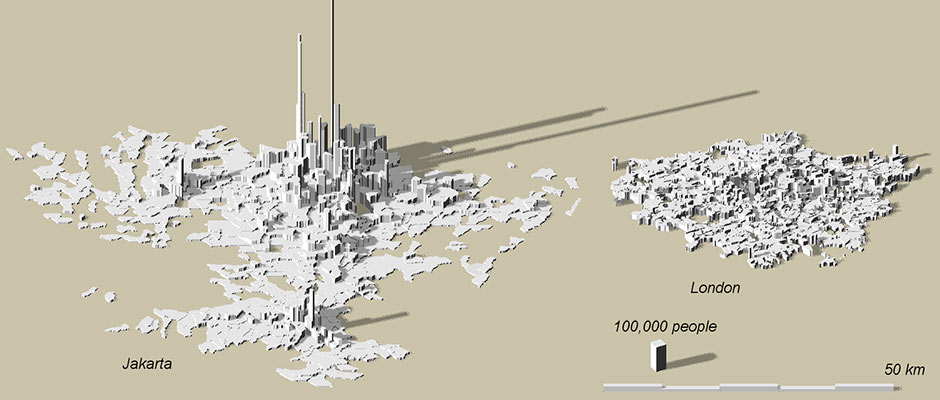

3D Rendering of Population Density in Jakarta and London. Source: Alain Bertaud.

The Blind and the Paralytic...MORE

During his professional journeys, he also attempted to gain deeper insights about cities by studying economics. As he chronicles in his book, this was an unusual route; most planners know very little economics and they remain uninterested in the subject. For him, however, it was a chance encounter with an urban economist while working in Port-au-Prince that set him on the path. Even so, his research also led him to conclude that while economists have generated deep insights in the into the nature of cities, they are not engaged with the daily problems of running a bustling metropolis:

We are facing a strangely paradoxical situation in the way cities are managed: the professionals in charge of modifying market outcomes through regulations (planners) know very little about markets, and the professionals who understand markets (urban economists) are seldom involved in the design of regulations aimed at restraining these markets. It is not surprising that the lack of interaction between the two professions causes serious dysfunction in the development of cities. It is the story of the blind and the paralytic going their owns ways: The planners are blind; they act without seeing. The economists are paralyzed; they see but do not act. (p. 2)The argument of the book is thus quite simple: that planners and economists should work together when developing urban policies. That much seems reasonable—who would dispute that two heads are better than one? But the next premise is likely a harder pill to swallow—that the city planners of the world need to learn and understand how markets work. This is particularly difficult because economics says that the planning profession has gotten things wrong. There are only a limited number of reasons planners should intervene. The rest can, and should, be taken care of by the market itself.

Insights from Urban Economics

Bertaud argues that urban economic theorists—through the use of math-based models—have generated several vital conclusions that need to be mastered if cities are going to function better.

The City as Labor Market

First is the need to view the city—fundamentally—as a labor market, as an agora or bazaar where residents can easily find matches between their own skills and the needed skills of employers. Successful matching is the path to higher incomes and the end of poverty.

Maximum Flexibility

Second, the city-as-labor-market requires maximum mobility and flexibility, so that people and businesses can find each other, and they can readjust their matches and housing as circumstances change. Geographic mobility is the route to social and economic mobility.

Population Density Emerges by Choice

Third, people don’t like to commute, and they are willing to pay higher housing costs to live close to their jobs. Therefore, long commutes must be compensated through lower-cost housing in the suburbs. If land markets operate properly, dense living in smaller units in the central city and less-dense living the suburbs is the result of households balancing the tradeoff, and thus choosing what’s best for them.

Sprawl is not Inherently Bad

Fourth, the footprint of the city—how far it extends into the countryside—is a result of the economics. Cities expand further out because residents have higher incomes, a more efficient transportation network, and/or a less productive agricultural hinterland. Sprawl is thus, at its heart, a result of free choice, and can be an efficient allocation of land.[2]

Land Markets are Vital

Lastly, labor markets and residential flexibility must be mediated through a well-functioning land market, where the prices of land reflect the relative demand for different locations throughout the city. When events change, the prices need to change too in order to incentivize repurposing the land for its most productive use.

Planning Reduces Flexibly

The planning profession, however, is more focused on limiting or restricting land uses and housing density. Rules are designed to preserve or prevent “bad” things from happening. Building height limitations are meant to lower density and shadows. Public housing projects are designed to give minimum size shelter to the poor. Zoning rules prevent single-family homes from being converted into apartment buildings. Bars and restaurants are banned from getting too close to residences....

Previously from Building the Skyline:

"The Economics of Skyscraper Height (Part I)"

And related:

Transportation: Affordable Proximity and the Dilemma for Planners