We may have an answer to the age old question: "To Whom?".Except this time more akin to Fat Marvin in Adam Smith's The Money Game, doing his best Ugly American bit as he performs on-the-ground due diligence for the boss' long cocoa speculation:

For some reason I picture Farmer Jones (with a couple Iowa State Masters Degrees) aw shucking the city folks and I think of Senator Sam Ervin (running intellectual circles around Attorney General John Mitchell, John Dean and the rest of "Richard Nixon's Secret Tapes Club Band"*) and his "I'm just a simple country lawyer" line.

...Going up to a Ghanaian outside a warehouse, asking "Say boy, any cocoa in there?" and the Ghanian saying "Nosuh, boss, no cocoa in deah" and then, as Marvin trudges off, the Ghanaian, who had been to the London School of Economics, goes back in the warehouse, chock-full of cocoa, puts his Savile Row suit back on, gets on the phone to the next warehouse and says in crisp British tones "Marvin, heading north by northwest".That's what I think of when I think of most—not all, most—financiers in the ag business.

From Bloomberg, Sept. 6:

The university’s holdings in developing markets have proved to be more trouble than they’re worth.

Fourteen years ago, a Brazilian farmer named Ruthardo Grun says he was terrorized by armed thugs who shot at him, burned down his shack, and chased him from land he was preparing to farm. Little did he know his battle to get the property back would end up pitting him against a company controlled by the world’s richest school: Harvard University.

The university’s endowment invested in the Brazilian company years after the events Grun describes. But a lawsuit Grun and five other farmers filed is just one of the long-running property conflicts Harvard inherited when it bet big on Brazilian agriculture almost a decade ago, accumulating vast tracts on the country’s impoverished northeastern frontier. The ongoing disputes include charges of so called land grabbing—the falsification of property titles and displacement of villagers—by companies Harvard later invested in. “I’d like to leave a piece of land to my four children, but I don’t know if it will be possible,” Grun says.

The South American mess shows the legal, financial, and reputational risks that Harvard faces because of its strategy of buying directly into developing markets. Most college endowments hire outside fund managers to spearhead such investments. Harvard Management Co., which oversees the university’s $37 billion endowment, instead bought properties through business partnerships that it formed with locals and controlled.

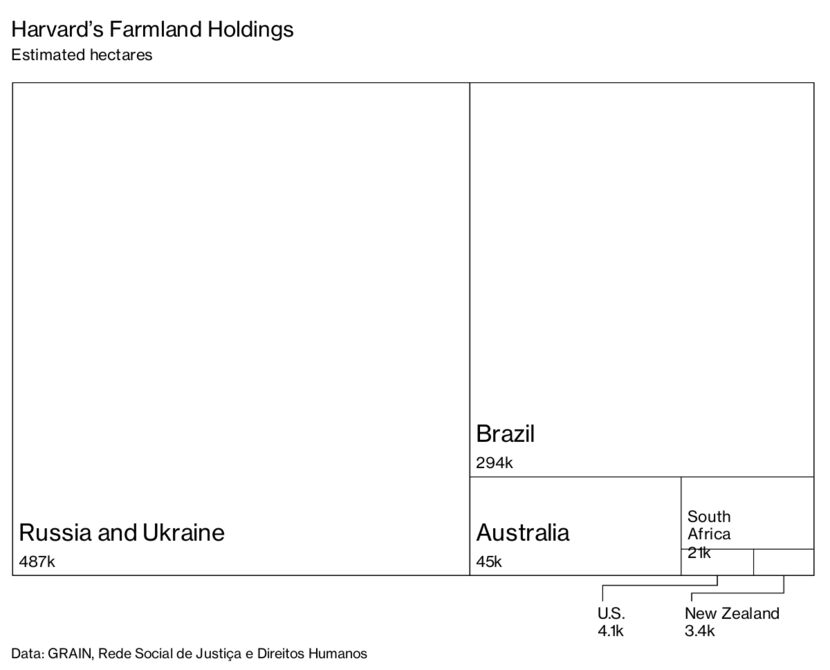

Over a decade, Harvard invested at least $1 billion in farmland, according to a just-released report from the activist groups GRAIN, based in Barcelona, and the Network for Social Justice and Human Rights, based in Sao Paulo. The organizations came up with their estimate after a year-long investigation of tax returns and local property records, as well as on-the-ground interviews. Harvard’s holdings included vineyards in California, dairy farms in New Zealand, and operations producing cotton, soybeans, and sugar cane in countries such as Brazil, South Africa, Australia, Russia, and Ukraine, and totaled 854,000 hectares, though some assets have been sold.

In response to questions about its farmland holdings, Harvard says it considers the environmental and social implication of its endowment investments. The university said in a statement that it has “instituted a more proactive approach to working with managers of new and remaining assets—a partnership that provides more oversight and ensures that we can leave the land and community better than when we first invested.”

Narv Narvekar, the endowment’s chief executive officer hired from Columbia University in 2016 to overhaul operations, has retreated from direct investing. He’s spun out teams of managers overseeing assets from real estate to hedge funds, sending them to start their own businesses while investing with them. Yet Narvekar is still trying to hammer out the future of the troubled natural resources portfolio, even as he sells some investments, including the New Zealand dairy farm and a eucalyptus plantation in Uruguay.

Now, as a new school year begins, Harvard’s far-flung farmlands are facing criticism for, among other things, their impact on ancient burial grounds and impoverished populations. “Harvard’s farmland deals should be a cautionary tale for institutional investors,’’ writes Devlin Kuyek, a researcher at GRAIN, whose mission is to support small farmers and social movements in poorer countries....MUCH MORE