It was nice that UBS said First Solar was an AI stock because a query of AI requires ten times as much electricity to spit out an answer as asking the GOOG. It's been worth about 28% for FSLR but the dirty little secret is: solar is not going to cut it as far as supplying the electricity that will be required for the AI build-out.

Here's Robert Bryce at his substack with the gory details, May 17:

Big Tech desperately needs more electricity to fuel its artificial intelligence push. These 10 charts show why AI needs gas-fired power plants.

ENIAC was a beast.

The world’s first general-purpose electronic computer contained 17,468 vacuum tubes, 10,000 capacitors, 1,500 relays, 70,000 resistors, and 6,000 manual switches. All those parts were connected by some 5 million soldered joints, most of which had to be joined by hand. In 1946, when it was completed, the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer weighed 27 tons, covered 240 square feet (22 square meters), and required 174 kilowatts of power.ENIAC used so much electricity that when it was switched on, it caused lights in the rest of Philadelphia to dim momentarily.

Six years later, John von Neumann, the mathematician and computer pioneer, unveiled MANIAC, the first computer to use RAM (random access memory). As I explained in my fifth book, Smaller Faster Lighter Denser Cheaper: How Innovation Keeps Proving The Catastrophists Wrong, that machine required 19.5 kilowatts of power. Author George Dyson said, “the entire digital universe can be traced directly” back to MANIAC, short for Mathematical Analyzer Numerical Integrator and Automatic Computer.

Many things have changed in the decades since ENIAC and MANIAC were first connected to the grid. But the power hungry nature of computing has not. The Computer Age has been defined by the quest for ever-more computing power and ever-increasing amounts of electricity to fuel our insatiable desire for more digital horsepower. As data centers have grown over the past two decades, concerns about power availability have surged. That history is relevant to me because I first wrote about data centers and electricity in 2000. In a piece for Interactive Week called “Power Struggle,” I wrote:

In the debate over power demand and the Internet, data centers are often exhibit No. 1. These facilities, also known as “server farms” or “telco hotels,” consume vast amounts of electricity. With power concentrations of 100 watts per square foot, a 10,000-square-foot data center can demand as much power as 1,000 homes. But unlike homeowners who turn their lights off when they leave for vacation, data centers require full power 24/7. In Seattle, a raft of new data centers is forcing the city to scramble to meet their needs. Over the next 24 months, the city’s utility expects a handful of data centers to raise its average daily demand by about 250 megawatts, an increase of nearly 25 percent over current loads. Other regions, including the San Francisco Bay and Chicago areas, are also facing power supply problems caused, in part, by data centers.

What’s old is new again. The rise of artificial intelligence has re-ignited concerns about electricity availability and strains on the power grid. Over the past two decades, worries that data centers would overwhelm local electricity providers have been muted because our computers keep getting more efficient. But this time, the concerns that there won’t be enough juice for AI and data centers are justified.

Yes, this time is different. And the key difference is Joe Biden’s EPA. On May 9, that agency published a rule in the Federal Register that, if it survives legal challenges, will force the closure of every coal-fired power plant in America and prevent the construction of new baseload gas-fired plants. If the rule survives those challenges, it will strangle AI in the crib.

Chart 1

Furthermore, the EPA aims to shutter massive amounts of coal-fired generation and prevent the construction of dispatchable power plants at the very moment forecasters expect massive electricity demand growth from AI and the electrify everything push. It’s also happening at the same time that regulators and policymakers are warning about the reliability of the electric grid. (More on those points in a moment.)

The same day the EPA published its rule, Vinson & Elkins, a Texas-based law firm with 700 lawyers that does extensive work in the energy sector, published a summary of the rule, explaining that it presents “heavy headwinds for new gas-fired plants intended to be operated above a 40 percent capacity factor.”

“Heavy headwinds” is incorrect. The EPA’s new rule is a de facto ban on new gas-fired power plants. As the firm explains, the new rule requires all existing coal plants and new gas-fired power plants to deploy carbon capture and sequestration equipment and “capture 90% of all CO2 emissions. The inevitable effect of this capacity factor cut-off will be to substantially reduce the chance that new base-load gas plants can be built.”

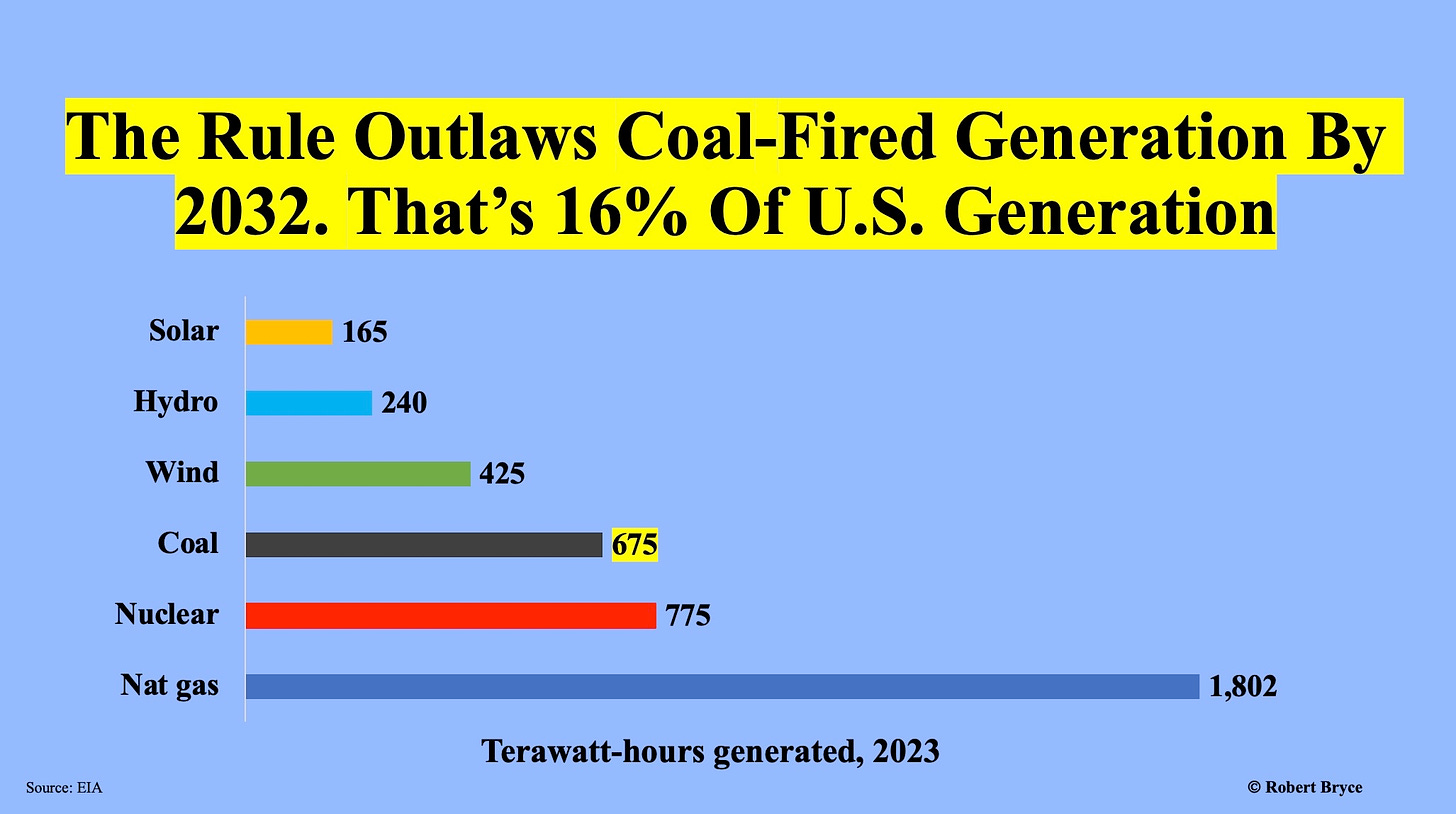

The hard reality is that CCS is not a viable option. Last month, Dan Brouillette, the former secretary of energy, who now heads the Edison Electric Institute, the trade group for investor-owned utilities, said, “CCS is not yet ready for full-scale, economy-wide deployment, nor is there sufficient time to permit, finance, and build the CCS infrastructure needed for compliance by 2032.” Given the impossibility of adding CCS to existing coal plants, those facilities will have to be shuttered. That would be disastrous. Why? As seen above in Chart 1, coal plants now produce about 16% of the electricity used in the U.S.

Chart 2

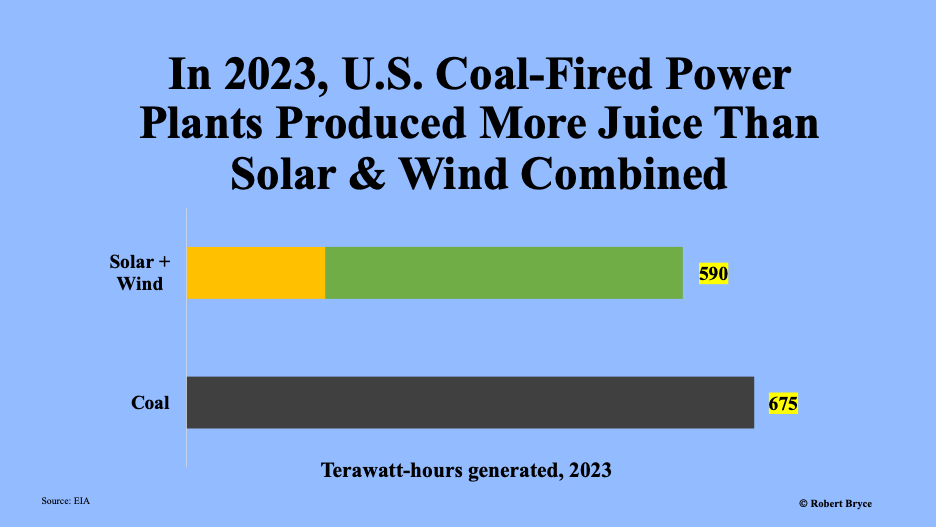

While coal-fired generation is declining, it is still a critical component of the American generation fleet. In fact, coal-fired power plants produced more electricity last year than wind and solar combined.

Regardless of the source of energy generation, Big Tech needs a lot more electricity. That will require more gas-fired power plants running at high capacity factors. Why? Wind and solar can’t provide the always-on power that data centers need. (Plus, those weather-dependent sources need massive amounts of land and new high-voltage transmission capacity.) Coal is out of the question. And new nuclear plants — regardless of the design — are still years away from being permitted and built.

That leaves natty.

In March, Toby Rice, chief executive of gas giant EQT, said, “There is a lot of excitement in the natural gas markets. We’ve talked a lot about LNG, but one market that’s emerging that we are equally as excited about is the AI boom that is taking place.” Last month, Tudor Pickering & Holt, a Houston investment banking firm, estimated that AI could require, in its base case, around 2.7 Bcfd of incremental natural gas. But the figure could also be as high as 8.5 Bcf/d by 2030. In mid-April, an analyst at Morningstar estimated the power burn for AI at 7 to 16 Bcf/d by 2030. Also last month, Rich Kinder, the executive chairman of pipeline giant Kinder Morgan, estimated AI would require 7 to 10 Bcf/d of new gas consumption.....