Now wanted by big credit bureaus like Equifax: Your alternative data

Lenders and credit bureaus say a bold new data push can expand credit to more consumers, but some worry the shift could sting the people it’s meant to help.

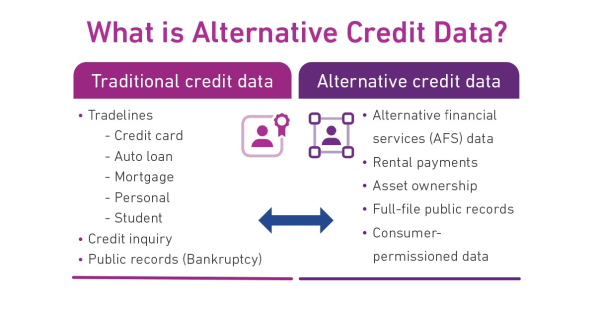

Take a look at a credit report from one of the big three credit reporting agencies, and you’re likely to see certain types of accounts listed: credit cards, mortgages, car payments, and student loans, for instance.

How you pay those bills impacts the credit score that lenders use to determine how risky you are. But other types of accounts don’t generally show up on your traditional credit report. Those include phone and electric bills, rent, and payments to many types of credit providers such as payday lenders, rent-to-own stores, and online personal lenders.

The country’s biggest credit bureaus—Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion—are trying to change that. As part of a growing push to expand the population to whom lenders can offer loans, the companies are helping lead an industry push to gather “alternative” credit data, in what’s been called one of the biggest changes to credit scoring in years.

The credit agencies, which already collect mountains of personal data on consumers, say the newer, specialized types of credit reports are meant to expand the credit files of millions of Americans, and potentially help raise the credit scores of lower-income people and others who are typically locked out of traditional credit. The new data could also help those without credit cards or mortgage loans, like younger consumers, immigrants, and others who have what the industry calls “thin” credit files with relatively little data.

“Alternative data from unconventional sources may help consumers who are stuck outside the system build a credit history to access mainstream credit sources,” said Richard Cordray, then-head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), in 2017, as the agency began an inquiry into the practice. Since then, each of the major three credit bureaus has acquired a company specializing in alternative data.

But in the wake of the 2017 Equifax breach and amid ongoing efforts to reform the industry, consumer advocates say alternative data raises more than just privacy concerns. Collecting increasing amounts of alternative credit data–especially data about short-term loans and utility payments–could lead to more adverse outcomes for some, especially in disadvantaged communities, says Christopher Peterson, a professor at the University of Utah’s College of Law and director of financial services at the Consumer Federation of America.

“With respect to discrimination and potential issues there, I have real concerns that alternative data sources may just end up creating new ways to replicate the same legacy of discrimination that’s already baked into a lot of the socioeconomic structures in our society,” he says.

Where the data comes from, and how

One of the leading arguments for including more data is that already vulnerable populations typically face high hurdles to gain access to affordable mainstream credit. A 2017 report by the CFPB found that consumers living in low income areas are 240% more likely than those in richer areas to become “credit visible”–to accumulate a first credit bureau file–not through positive data like timely credit card payments, but through negative information like overdue bills....MORE

Black and Hispanic people are also disproportionately affected by thin or nonexistent credit bureau files, the agency has said. In all, the CFPB estimated in 2017 that about 26 million Americans had no credit history, and another 19 million had too little data to produce a credit score.

“Part of this push for alternative data is recognition that people are being locked out of opportunities that having a good credit score is associated with,” says Tamara Nopper, an assistant professor of sociology at Rhode Island College, who has written about credit issues.

Research into alternative data shows that it can bring benefits to individuals’ credit scores. A study released by the New York City comptroller’s office in 2017 using Experian data found that about 28.7% of a sample population studied gained a credit score for the first time using data about their rental histories, with the average new score at 700 points, according to the report. Over two-thirds of city renters would see their credit scores go up with their rental histories included, the analysis found, while just 6% would see a decline. Another 18% would see essentially no change.

But not all credit is created equal, says Peterson, who predicts that while some kinds of alternative data could help certain consumers get access to good credit, others might be newly tagged as too risky for mainstream credit. (For their part, the credit bureaus generally emphasize that banks and other lenders each have their own criteria for credit decisions.)...

Now, about your Tinder score...