From Cabinet magazine:

Inside Jobs

Geoff Manaugh

The books and manuscripts were disappearing from a room no one seemed to be entering. Its doors were almost never opened, the room itself closed to public view. There was no believable explanation for where the materials might be going, so the least believable reasoning soon took hold. It was the work of the devil, the residents said. A poltergeist. A symbolic act of God meant to communicate something, if only they could interpret the signs.

This was, after all, a monastery—indeed, one of the world’s most picturesque, Mont Sainte-Odile, perched high in the mountains of France, nearly on the border with Germany—and its library was vanishing into thin air. A manuscript here, a bound volume there; five, six, a dozen, all quickly adding up to nearly a thousand key pieces of church scholarship missing from the shelves and tables.

When the police were finally notified, they chose not to perform an exorcism. Being a secular institution, they instead installed a hidden surveillance camera, and, in May 2002, the truth came to light. It was not a ghost at all, but an engineering teacher from Strasbourg. He had been entering the room through a long-forgotten secret passage, access to which was hidden inside one of the bookcases. Unseen—indeed entirely unsuspected—he was able to remove the library’s priceless collection piece by piece, emerging from the walls to take entire shelves of books at a time.

Perhaps more spectacular than the teacher’s indirect method of approach was how he came to know the passage was there in the first place. According to the Guardian, this otherwise law-abiding engineer first learned about the route “after discovering a forgotten map in public archives” revealing how the monastery’s attic was covertly joined to the library on a lower floor. This chance discovery of a discarded floor plan made him one of the very few people in the world who knew the architectural connection existed at all; it had long ago ceased being used by the monks themselves, having fallen into a state of neglect resembling spatial hibernation.

Bringing the passage back into service as a reliable form of internal circulation was not, in fact, easy. According to some newspaper accounts, doing so required scaling the outside walls of the monastery, then navigating a precipitous attic stairway. According to others, the man posed as an overnight guest staying in another part of the monastery that had been converted into a hotel; carrying a suitcase, he would slip into a room with access to a hidden passageway, climb down a rope ladder, then enter the library through the trick bookcase. Some reports also claim that he had to locate “a hidden mechanism” tucked inside the wall that would cause the back of the bookcase to flip open, allowing entrance into the library. Regardless of how he ultimately gained access to the books, his actions transformed the confines of the monastery into a kind of three-dimensional puzzle. Indeed, the very fact that these accounts diverge suggests something of an epistemological uncertainty at the heart of such crimes: that a burglar can misuse a piece of architecture so radically it becomes almost impossible to narrate what actually took place there.

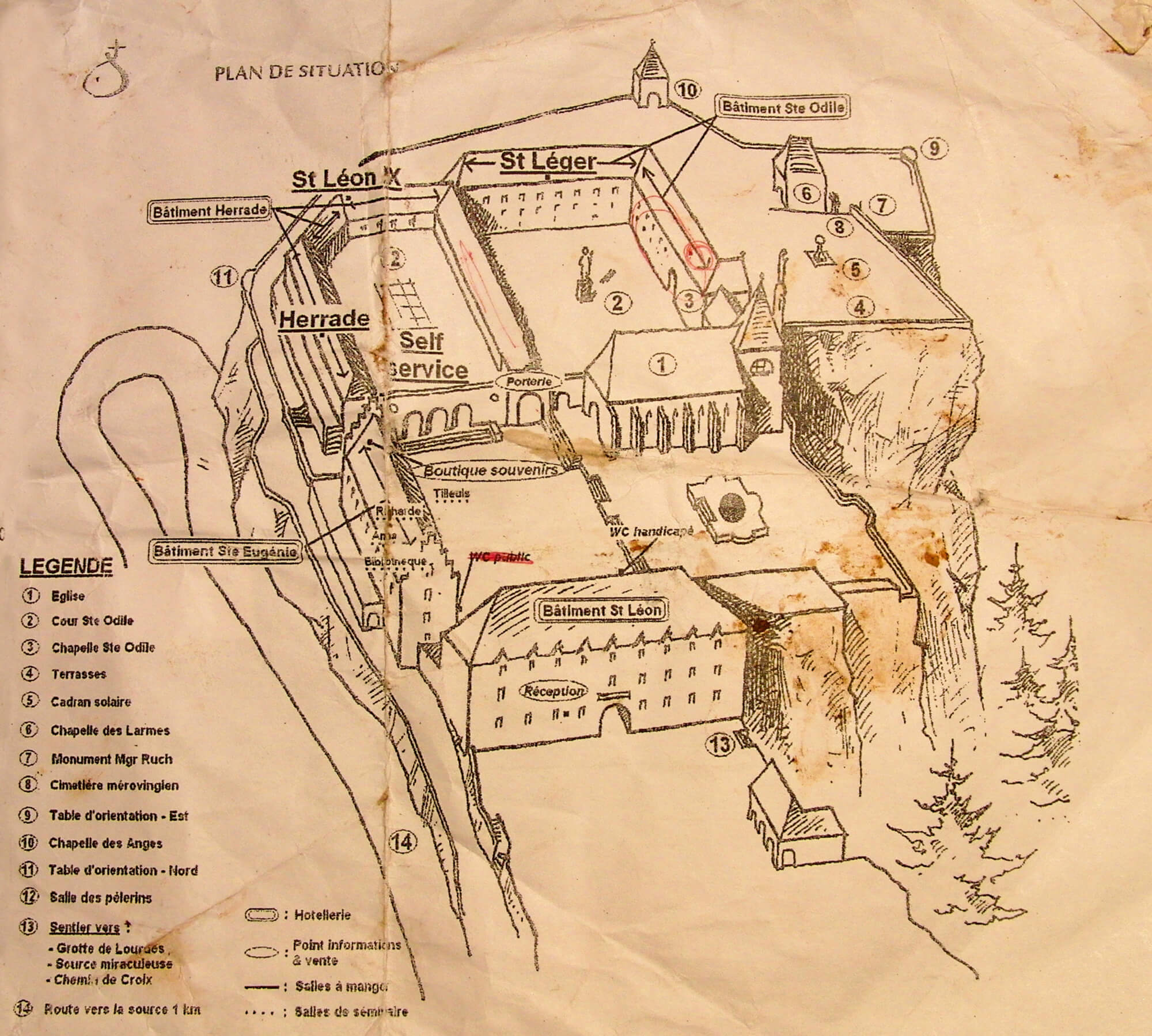

Map of monastery and adjoining

hotel. This map was obtained and used by an amateur sleuth who visited

the monastery in May 2011 looking for its secret passages.

Courtesy adventurecycletour.wordpress.com.

Courtesy adventurecycletour.wordpress.com.

Half a world away, another prolific book thief found equally furtive ingress through similar spatial means. An avid lock picker, expert counterfeiter, and methodical planner committed to researching the targets of his heists, Stephen Blumberg stole an estimated twenty million dollars’ worth of rare books and manuscripts from institutional archives and academic libraries around the United States.The writer is author of A Burgler's Guide to the City which we visited in 2016's "A Burgler's Guide To The City--How a Criminal Sees the World".

His plan for hitting the rare books collection of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles was characteristic: researching the history of the building, Blumberg had learned that a series of disused dumbwaiters had once functioned to deliver books between floors. The dumbwaiters were no longer active, but the shafts inside the walls of the library still offered a direct connection to book stacks that were otherwise inaccessible to the public....MORE