Harold Vilches, a 23-year-old Chilean, exported $80 million in contraband gold. It all started with a Google search.

As the minutes ticked by on the afternoon of April 28, 2015, Harold Vilches watched stoically while customs officers at Santiago’s international airport scrutinized his carry-on. Inside the roller bag was 44 pounds of solid gold, worth almost $800,000, and all the baby-faced, 21-year-old college student wanted was clearance to get on a red-eye to Miami. Vilches had arrived at the airport six hours early because he thought there might be some trouble—he’d heard that customs had recently seized shipments from competing smugglers. But Vilches had done this run, or sent people to do it, more than a dozen times, and he’d prepared his falsified export paperwork with extra care. He was pretty sure he wouldn’t have any trouble. While he waited, he texted his contacts in Florida, telling them he’d already cleared customs.The plan was to hand off the gold at the Miami airport to a pair of guards, who would load it into an armored truck for the short trip to NTR Metals Miami LLC, a company that buys gold in quantities large and small and sells it into the global supply chain. The modesty of its shabby office, where a receptionist sits behind an inch-thick acrylic barrier, belies the amount of business that goes on inside. U.S. Department of Justice investigators believe NTR Metals Miami has bought at least $3 billion in South American gold in the past four years, much of it from illegal mining operations, people familiar with the investigation say.

Vilches didn’t need this headache. In just two years he had rapidly risen in the ranks of Latin American gold smugglers. Although he was barely old enough to order a beer in Miami, he’d won a $101 million contract to supply a gold dealer in Dubai. That hadn’t exactly worked out—the Dubai company was after him for $5.2 million it says he misappropriated—but still, in a brief career he’d acquired and then resold more than 4,000 lb. of gold, according to Chilean prosecutors. U.S. investigators and Chilean prosecutors suspect almost all of it was contraband.

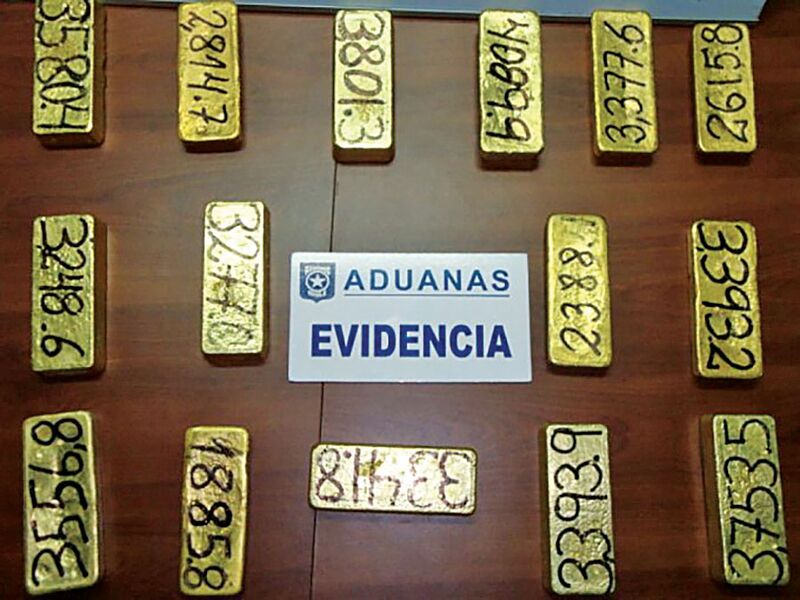

That evening at the airport, Vilches employed his standard cover story, saying that the gold came from coins acquired from customers and recast as ingots. The customs officers weren’t buying it. The laboratory Vilches had used to vouch for the gold wasn’t government-certified, they said, and they doubted his claims that the gold had come from coins. Vilches was irate. He couldn’t believe it when the man behind the desk called his boss and then relayed orders from above: If it’s Vilches’s gold, seize it.

Investigators with the Policía de Investigaciones, Chile’s equivalent of the FBI, had been monitoring Vilches for months, intercepting his phone calls and scouring the export papers he’d submitted. The kid was clever, they agreed, but who was he working for? “I thought there was someone behind him, always,” says José Luis Pérez, a Chilean prosecutor on the case.

After the airport officials confiscated Vilches’s gold, they let him go. For the next 15 months, Chilean authorities allowed Vilches to bring illegal gold in and ship it out as they built a case, searching for associates and those above him. They listened in on various telephones, read Vilches’s text messages, and followed couriers. They watched as smugglers brought gold south from Peru, across remote stretches of desert and through valleys in the Andes Mountains, or west from Argentina, driving over the snowy mountain pass in the shadow of 22,800-foot-high Aconcagua, then down to Santiago and Vilches’s headquarters, a place police nicknamed “The Bunker.” Inside, Vilches assayed, weighed, and paid for the gold. He melted it down and recast it as ingots, then flew it, or used a family member to fly it, to Miami.

To their growing amazement, the police never found the larger organization they presumed was supporting and protecting Vilches. There was, as far as they could determine, no bigger fish. Finally, in August 2016, they arrested him. Investigators say they have documented $80 million in gold shipments that moved through his hands via eight shell companies he established in Chile and Miami—and they think there was much more. They charged Vilches and four associates, including his wife and her father, with racketeering, smuggling, customs fraud, and money laundering. None of them have been tried, and the case remains open. Vilches’s wife and father-in-law declined through their lawyer to comment. Today, Vilches lives with his wife in an apartment in a rundown part of Santiago; he’s under house arrest from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m.

In exchange for his release from jail, Vilches provided extensive testimony that has allowed Chilean prosecutors and the U.S. Department of Justice to try to build a huge, multinational gold smuggling case. Interviews with police and prosecutors in Chile and the U.S. and hundreds of pages of police files describe Vilches’s part in a black market that adds literally tons of illegally mined and contraband gold to the international economy every year.HT: LongReads--He Learned it All on Google and YouTube: How to Become a Gold Smuggler

In the past decade and a half, global gold consumption has risen by almost 1,000 tons a year, to about 4,300 tons, according to the World Gold Council, a London-based industry group. Legal mining operations haven’t kept up with demand, so illegal mines controlled by criminal gangs, from the Amazon to central Africa, help cover the deficit, according to Verité, a nonprofit group in Amherst, Mass., that’s researched the illegal gold trade. A 2016 Verité study found that five countries in Latin America shipped 40 tons of gold from illegal mines to the U.S. in one year, almost twice the legal exports from those countries. South America’s illegal gold mines, most of them in the Amazon basin, are toxic pits in which mobs of laborers use fire hoses and mercury to extract nearly pure gold nuggets from the red earth. According to a finding by the United Nations, the industry thrives on child labor, devastates the environment, and enables prostitution at ramshackle camps around the mines. The gold moves from smuggler to smuggler, then into a network of refiners and traders, all feeding the world’s voracious demand....MORE