I can't remember the word I'm looking for and I'm too lazy to come up with a neologism, so we'll stick with hindcast.

From FT Alphaville:

Jobs, automation, Engels’ pause and the limits of history

Here’s a story that you may have heard.

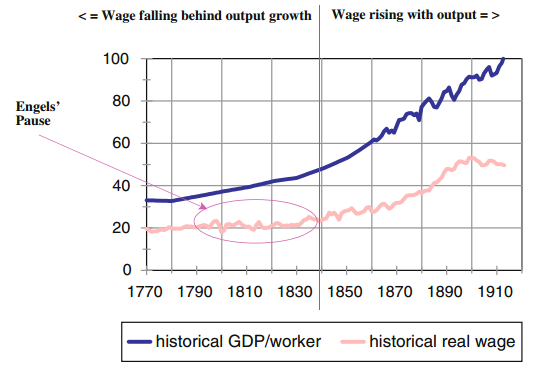

Median wages and living standards are stagnant, and by some measures they have worsened, having decoupled from productivity growth for several decades.

Income inequality has climbed, as a higher share of income has increasingly gone to the owners of capital, and a correspondingly lower share to workers. Somewhat mysteriously, high profits have not been redeployed as significantly more investment.

Anecdotal evidence of remarkable new technologies suggests that the effects on the economy will be profound, but it’s not clear how. It’s possible that the available data-gathering techniques are failing to capture the impact of these technologies.

Sound familiar?

Yet I’m not talking about a modern advanced economy.

I’m talking about the UK in the first four decades of the nineteenth century, a period that economic historian Robert C Allen has labeled “Engels’ Pause”.

—————

Do such commonalities between the past and today hold any useful lessons for us?

The lazy but common retort to the idea that technological advancement would massively displace workers has long been to accuse the fear-monger of having perpetuated the lump of labour fallacy.

Luddites!, the response goes, technology constantly takes jobs from workers, but the gains in efficiency lead to a surplus for the owners of companies (via higher profits) and for the consumers of their products (via lower costs). Those surpluses are then spent on other investments and consumer products, some of which we haven’t yet imagined but nonetheless will lead to more jobs in other sectors.

Buy a cheaper car, and you have more money to spend on lavish restaurants, which leads to more jobs for chefs and waiters and sommeliers, and so on.

The popularity of such books as Second Machine Age and Average is Over, along with the superficially appealing nature of technology and “robots”, have led to a renewed interest in the possibility that a different dynamic will soon apply — a dynamic in which technology displaces labour at an unexpected and perhaps unprecedented scale.

It’s true enough to say that we are all equally idiots about the future, and that nobody really knows if modern technologies will affect our professional lives in radically new ways. But that way of thinking is no fun at all, and the issue is worthy of serious discussion even without perfect foresight....MUCH MORE