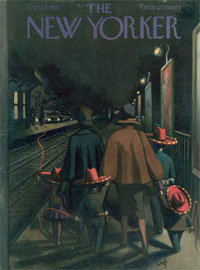

IN IMMORTALITYS. N. Behrman

The New Yorker

October 13, 1951: 41-80The activities in the United States a half century ago that made possible the advent of the Duveen Era were on a titanic scale. The tumultuous exertions and accomplishments to be found in the great coal and iron mines, in the flourishing department stores, in the prodigious chains of five-and-tens, in the great public utilities and networks of railroads and banking houses, in the breathtaking corporate pyramiding that reached its climax with the merging of ten giant steel companies into J. P. Morgan's "billion-dollar trust," in the apogee of finance capitalism, which was bringing its masters a material wealth without precedent—all this was interesting and praiseworthy, as far as it went, but to the art dealer Joseph Duveen, head of the firm of Duveen Brothers, who eventually became Lord Duveen of Millbank, it was merely an overture to the fantastic and costly opera he was himself prepared to produce.The emperors of the immense commercial realms of the period were rich in power but poor in panoply. It had all happened so quickly. For the most part, the millionaires of this era could trace the origins of their fortunes to the struggles of their own youth—on farms, in offices, in machine shops or butcher shops, behind the counters of country stores. William Randolph Hearst and Andrew Mellon and John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and William C. Whitney were among the exceptions; they were the aristocrats, with a tradition of substantiality that reached back a generation. Most of the rest—H. E. Huntington and Henry Clay Frick, Andrew Carnegie and Benjamin Altman, P. A. B. Widener, E. T. Stotesbury, and Samuel H. Kress—remembered shirtsleeved rather than imperial pasts. How could they obliterate these memories? How could they drown them in splendor? Duveen showed them how.The passion of these newly rich Americans for industrial merger yielded to an even more insistent passion for a merger of their newly acquired domains with more ancient ones; they wanted to veneer their arrivisme with the traditional. It would be gratifying to feel, as you drove up to your porte-cochere in Pittsburgh, that you were one with the jaded Renaissance Venetian who had just returned from a sitting for Titian; to feel, as you walked by the ranks of gleaming and authentic suits of armor in your mansion on Long Island—and passed the time of day with your private armorer—that it was only an accident of chronology that had put you in a counting house when you might have been jousting with other kings in the Tournament of Love; to push aside the heavy damask tablecloth on a magnificent Louis XIV dining-room table, making room for a green-shaded office lamp, beneath which you scanned the report of last month's profit from the Saginaw branch, and then, looking up, catch a glimpse of Mrs. Richard Brinsley Sheridan and flick the fantasy that presently you would be ordering your sedan chair, because the loveliest girl in London was expecting you for tea.It was Frick's custom to have an organist in on Saturday afternoons to fill the gallery of his mansion at Seventieth Street and Fifth Avenue with the majestic strains of "The Rosary" and "Silver Threads Among the Gold" while he himself sat on a Renaissance throne, under a baldachino, and every now and then looked up from his Saturday Evening Post to contemplate the works of Van Dyck and Rembrandt, or, when he was enthroned in their special atelier, the more frolicsome improvisations of Fragonard and Boucher. Surely Frick must have felt, as he sat there, that only time separated him from Lorenzo and the other Medicis. Morgan commissioned the English art authority Dr. George C. Williamson to prepare catalogues of his vast collections. Williamson spent years travelling all over the world to check on the authenticity and the history of certain items and to supervise the work on the catalogues. The last one he completed for his patron was "The Morgan Book of Watches." For the illustrations, gold and silver leaf was used, laid on so thick that the engraved designs of the watches could be reproduced exactly. Morgan was in Rome when he received this catalogue, on Christmas Day, 1912, and he cabled Williamson, in New York, "IT IS THE MOST BEAUTIFUL BOOK 1 HAVE EVER SEEN." It was lying by Morgan's bedside when he died in Rome, early in 1913.Duveen boasted that he understood the psychology of his dozen biggest customers much better than his competitors did. In his peculiar semantics, "to understand psychology" meant to be able to guess how much the traffic would bear, and under that interpretation his boast was not an empty one. He always knew how to shift the interest of his customers—or, more accurately, his protégés—from their original fields of accumulation to his own, and to persuade them, moreover, that his was the more exalted. The truth was that after having spent a lifetime making money, Duveen's protégés were rich enough to go anywhere and do anything but didn't know where to go or what to do or even how to do nothing gracefully. After the Americans had splurged on yachts and horses and houses, they were stymied....MORE

Previously:

Duveen, The Greatest Salesman in the World: Early Days

One of the Gainsborough's Duveen sold to Frick: The Mall in St. James Park c. 1783

One of the Gainsborough's Duveen sold to Frick: The Mall in St. James Park c. 1783