Currencies: Crisis & Opportunity

February 29, 2012Meanwhile at the WSJ Europe's The Source blog:

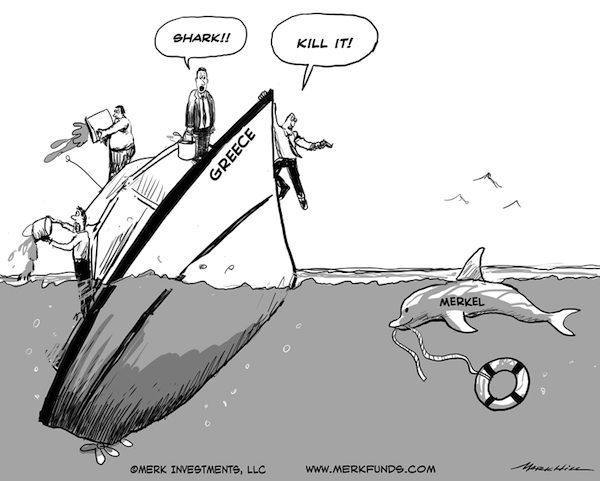

The road to hell is paved with good intentions. According to some estimates, Germany will contribute approximately 28% of the €130 billion (approx. US$170 billion) bailout recently agreed for Greece; yet, rather than expressing their gratitude, protestors on the streets in Athens burn German flags. While some are celebrating that Greece is – at least for now - not falling into chaos, we are rather concerned about major shifts in European policy making that have unfolded in recent months. Where there is a crisis, there may be opportunities – but not necessarily in the places one might expect.

Let’s take a step back and ask why Germany is being so generous:

It’s the last point that must not be underestimated. A crucial driver behind the “European project”, the founding of the European Economic Area, succeeded by the European Union, as well as the Euro itself, is a desire by policy makers to create a politically and socially stable, peaceful Europe. Throughout the process, Germany has been very willing to subsidize many corners of Europe. Indeed, while there is public backlash against the German chancellor Merkel’s handling of the bailouts, the German opposition has indicated it might be even more willing to write checks, going as far as suggesting that Southern Europe needs a modern-day Marshall Plan.

- The exposure of financial institutions towards Greek debt. A lot of progress has been made in making the European banking system more robust; the envisioned 53% write-down of Greek debt is priced into markets already. Concerns regarding outright exposure to Greece have abated. Rather, concerns linger about the inter-dependency across financial institutions, the potential “contagion” as other countries – and thus financial institutions across Europe and beyond - may be considered at increased risk of default.

- In 2010, Germany exported €5.9 billion worth of goods to Greece, a 10.2% drop versus the previous year. While significant, Germany’s $3 trillion economy could stomach losing exports to Greece.

- Germany’s desire for peace in Europe.

Technocrats will argue that a Greek bailout is necessary. Note, though, that while Fitch Ratings just upgraded Iceland (to BBB- from BB+), it downgraded Greece from CCC to C (“default highly likely in the near term”). Iceland’s situation is different, but shows that undergoing shock treatment might lead to a faster recovery than the drama Greece has chosen to pursue.

Importantly, Germany now “owns” the Greek drama. As “experts” impose frugality on Greece’s budget, it is those experts that will be blamed by Greek politicians for any problem or failure that is encountered. Until recently, the reality was rather different: at the time, it was the bond market that was in charge, dictating the terms of how policy makers in the entire Eurozone acted. We have frequently commented on this ‘dialogue’; if it hadn’t been so serious, it would have been farcical to see policy makers commit to implement reform based on pressures by the bond market; the moment the pressure abated, however, those promises became distant memory, only to get a prompt reminder by the markets that there was to be no fooling around, by way of renewed upward pressures on rates.

For now, policy makers have won the upper hand. Relative calm has come back to the market, but at a price: for Germany, it is that it now owns the Greek problem. And it remains a problem, for it has only been patched up; any reference to Greece’s financial health is still an oxymoron. It is not good enough to have averted a Greek meltdown: if Europe does not want to disintegrate, policy makers must find a way for Greece to own its own problems.

Another price has been paid on the monetary front. Since November 1, 2011, when Mario Draghi became President of the European Central Bank (ECB), we’ve witnessed a seismic shift in how monetary policy is being conducted. While we applaud Draghi for his clarity and determination, his decision to provide almost €500 billion in three-year financing to banks (LTRO) at a mere 1% may come at a tremendous cost.

Together with another dose of cheap financing to be provided at the end of February, the ECB may have created a monster. The good intentions are clear: banks require more capital, yet market conditions remain difficult and sovereigns may not have sufficient resources to inject capital. Unlike the Federal Reserve (Fed) that brags about delivering a $70 billion plus “profit” to the Treasury (the dirty secret is that the more money a central bank prints, the more securities it buys, the more interest it earns and thus, the more in “profit” it earns, ignoring the not-so-subtle fact that purchasing power is put at risk in the process), the ECB “splits the coupon”, charging only 1% on loans, boosting the profits of European banks. However, the ECB’s LTROs are a Faustian bargain, as there is no way in heaven or hell – at least in our estimation – that such a vast amount of liquidity – in the order of magnitude of a trillion dollars – can be absorbed in three years, when it is time to pay it back....MORE

Dollar, Yen Yield Link May Prevent Further Gains

One of the more enduring cross-market correlations is the link between short yields and the dollar/yen pair.

Indeed, it’s famous. Bank of Japan governor Masaaki Shirakawa acknowledged less than a year ago that the yen’s level against the dollar was highly correlated with the differential between two-year U.S. and Japanese notes.

And, unlike some correlations, it isn’t rocket science. A wider spread tempts Japanese investors into U.S. assets; a narrower one sends them home to look elsewhere. Simple.

But, for a while now, there’s been a heavy spanner clanging about in the works of this correlation, tossed in by the Federal Reserve with its post-crisis pledges of enduringly low rates, which act as a cap on U.S. yields....MORE

In recent days, however, they have crept higher nonetheless, by about 0.1 percentage point, lifted by relatively upbeat U.S. economic numbers, higher oil prices and a growing sense that the Fed’s monetary stance may not be quite as loose as it has been.