Andrey Mir's book "Postjournalism and the Death of Newspapers. The Media after Trump: Manufacturing Anger and Polarization" is a very thoughtful overview of the transformation of the news media over the last twenty years or so. The essence is a fight for survival in a media ecology that changed incredibly fast and faster than those in the middle of the change ever imagined.

The second rule of ecology—the first rule being "EVERYTHING IS CONNECTED"—the second rule is "Life will attempt to adapt to changed circumstances". This is true of everything from slime molds to the New York Times.

And with that longer than usual introduction here is Mr. Mir writing at New Explorations Weblog (Studies in Culture & Communication):

Postjournalism and the death of newspapers

Fake news is an overhyped issue. The greatest harm caused by media is polarization, and the biggest issue is that polarization has become systemically embedded into both social media and the mass media. Polarization is not merely a side effect but has morphed into a condition of their business.

The recent surge in polarization originated from the advent of social media, which unleashed the authorship of the masses. In this newly emerged horizontal communications, alternative agendas were gradually shaped. It soon became apparent that this direct representation of opinions forms very different agendas than those shaped by the more traditional representative form of opinion- making, the news media.

The clash between the alternative agendas of social media and the mainstream agendas of the news media entailed political polarization, which produced two waves of anti-establishment movements. The first wave was caused by the initial proliferation of social media in the early 2010s, when digitized educated progressive urban youth ignited the Arab Spring, the Occupy movement in the US, the protests of ‘indignados’ in Europe and worldwide protests against the old institutional establishment. The second wave of polarization started in the mid-2010s, when social media had permeated society deeply enough to reach and influence those who are older, less educated, less urban, and less progressive. The resultant wave of conservative, right-wing and fundamentalist movements influenced election polls and struck streets around the world.

Amid the growing political activity of the masses, facilitated by new media, it quickly became apparent that social media platforms result in higher end-user engagement. The more engagement, the more time is spent on the platform, the more user preferences are exposed, and consequently the more precise ad targeting can be. Engagement, much needed for the platforms’ business, appeared to be tied to polarization. There is nobody’s evil intent behind such settings; the hardware of this media environment just requires this software – polarization.

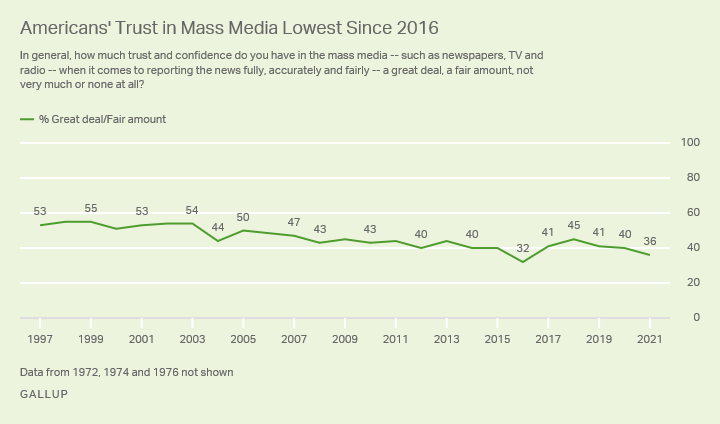

In parallel, a tectonic shift occurred in old media. The news media business used to be funded predominantly by advertising, but advertising fled to the internet. The entire news media industry was forced to switch to another source of funding – reader revenue.

The scale of this shift is tectonic. The last time the mass media changed the source of revenue on such a scale was the period 1920–1950, when newspapers switched from selling copies to selling ads. That period coincided with the advent of radio and TV, so the change in the business model of journalism was not really reflected upon, as more attention was directed to the fascinating cultural impacts of the new electronic media.

However, by the 1980s, the discipline of the political economy of the mass media emerged, which revealed the impact of advertising money on agenda-setting in the news media. This brought about the framework for the understanding of the news media that the public still uses today. The media are corporate-owned entities representing the interests of ruling capitalist elites; they basically sell goods, distract from pressing social issues and manufacture consent amongst the audience.

Meanwhile, the very hardware of the news media industry has drastically changed since then. Over the last 10–15 years, both advertisers and audiences have fled to better platforms, where content is free and far more attractive, and ad delivery is cheaper and far more efficient. The internet and social media have taken away revenues from the news media. The classical business models of the news media, news retail and ad sales, have been shaken up so violently that it is hard for the media to survive.

Because of the internet, ad revenue in the media has declined much faster than reader revenue. The media were therefore forced to switch to the reader revenue business model aimed to sell content. However, as content is free on the internet, it is hard to sell. People almost always already know the news before they come to news websites because they invariably start their daily media routine with newsfeeds on social media. Increasingly, therefore, if and when people turn to the news media, it is not to find news, but rather to validate already known news.

Thus, the reader revenue the news media now seeks is not a payment for news; it is actually more a validation fee. The audience still agrees to pay for the validation of news within the accepted and sanctioned value system. After switching from ad revenue to reader revenue, the business of the media has mutated from news supply to news validation....

....MUCH MORE

And here is Mr. Mir being interviewed at Discourse Magazine, April 13, 2021:

Factoids and Fake NewsMartin Gurri interviews Andrey Mir about the future of journalism

Shortly after the publication of the first edition of “The Revolt of the Public,” I received a little book with the intriguing title “Human as Media: The Emancipation of Authorship.” The author was Andrey Miroshnichenko—having found his last name to be unpronounceable by English speakers, he later shortened it to Mir—and the book was a brilliant explanation of the internet.

To an uncanny degree, Mir and I shared the same assumptions, observations and sources. The same obscure passage from José Ortega y Gasset can be found in both books. It seemed fated that we would establish a lively long-distance intellectual friendship, sharing odd bits of information from the ever-expanding media universe. My understanding of the digital landscape would have been vastly impoverished without this exchange.

At present, Mir is a media scholar at York University, Toronto. He is a native of Russia and worked for 20 years in the Russian business media before turning his attention to the impact of new media on society. Mir is a prolific writer who has authored many books on journalism, communications and politics. He also blogs at Human as Media.

His latest book, “Postjournalism and the Death of Newspapers” (2020), breaks new ground in our understanding of the relationship between traditional and digital media. In “Postjournalism,” Mir explains the ideological corruption of newspapers—for reasons mostly related to business—and predicts the extinction of journalism as an institution and of the news as an industry, driven by an inexorable demographic transition. For anyone interested in the past, present or future of the news and of media generally, “Postjournalism” will be a revelation.

This interview was conducted in writing and has been edited for brevity.

MARTIN GURRI: You predict with great confidence that newspapers will soon go extinct as an industry, and even provide the time of death: the late 2030s. Has anything occurred since the publication of “Postjournalism” to change that deadline? Is it possible that some innovation or change in public tastes might bring the newspaper back to prosperity? And can you describe what their “death” would look like?

ANDREY MIR: I don’t think anything can change the slide of the newspaper industry toward extinction. Some local events can slightly correct the development, as has happened in the U.S. with Donald Trump. Now that Trump has left the White House, the largest media outlets have lost a driver for business and are returning to a declining trajectory. But no newsroom innovations or investor’s efforts can change this trajectory, since the main problem is on the opposite side, on the side of consumption, not production.

The internet revealed that the business of the news media rested not on information but on the lack of information. Those conditions are gone. The market is already willing to abandon newspapers, but society is not yet ready. Social habits have slowed down the process. But it is demographics that have begun the final countdown. This is why it is possible to calculate the deadline, figuratively speaking. Millions of students today have never even touched a newspaper. They simply do not know how to consume the press, nor are they aware of why they should do it. As soon as this generation takes command, newspapers are done. Hence the last date for the industry—the mid-2030s.

The process of the newspapers’ extinction will look like a comet with a condensed core and long tail. Circa the mid-2020s, the biggest newspapers will stop printing and declare the final transition to digital. For many others, this will be the moment of veiled extermination. Those newspapers that have noncommercial funding will last a bit longer. But even the funding secured for the lucky few will make no sense if there are simply not enough readers around. So the media industry has about five years of agony and ten more years of convulsions ahead. The little that remains of the industry afterward will be vintage art forms.

But the main issue is that, while discussing newspapers, we are in fact talking about the fate of the news media as an industry and of journalism as an institution. Their business was in print and on the air, and it was based on the limited access of the public to the news. Old journalism does not have a viable business model in the digital world.

GURRI: What are the historical forces that have driven traditional journalism into “post-journalism”? Can you explain the difference in the ideals and value systems of the two practices?

MIR: Throughout the entire 20th century, the news media was funded predominantly by advertising, which brought in 70%-80% of the media’s revenue. The internet took this business away from the media. In 2013, the ad revenue for American newspapers dropped below the level at which the industry started measuring it in 1950. A dramatic and yet unnoticed switch had happened: The news media in general became dependent not on ad revenue but on reader revenue....

....MUCH MORE