The writer refers to the "first bubble" but in my weltanschauung a bubble requires not just overinvestment but a level of abstraction in the form of shares or tradable debt or futures/forwards or insurance contracts in which to speculate on the overinvestment.

This was a characteristic of both the Mississippi Bubble and the South Sea Bubble as well as the lesser-known Dutch 'Wind-trade', which also popped and dropped during those memorable months of 1719 - 1720 and gave us such incisive commentary as:

On the other hand, as pointed out in this piece, despite the lack of bubble-making spec instruments, the overinvestment in printing presses was real and it was magnificent, as was the ensuing crash.

From The Times' (and Sunday Times') James Marriot at his personal substack, Cultural Capital, October 2:

How to spot AI writing, the death of zombie art, the first tech bubble, out of touch politicians and RIP Tony Harrison

....The birth pangs of print

The writer Derek Thompson has written and spoken very interestingly about how many transformative new technologies start off as bubbles. Railways, the telegraph, the radio, the car — all these technologies prompted massive excitement that prompted initial over-investment. Though the excitement was eventually justified, the first stage of hype created bubbles which popped.In time the technology then finds realistic use-cases and gradually surges back, often taking advantage of all the infrastructure that was built in the first phase of wild over-enthusiasm. Thompson believes something like this may be true of AI.

Interestingly, according to Andrew Pettegree’s fascinating history of the early years of print, The Book in the Renaissance (highly recommended), the invention of the printed book followed the same trajectory. Was print the first tech bubble?

The parallels are really remarkable. It began with excitement:

Print spread like wildfire, fuelled by the enthusiasm of a sophisticated urban market. But this enthusiasm was based more on fascination with the new technology than on rational calculation. It was still far from clear whether Italy’s community of readers could deal with so large a large a volume of printed books.

Then came the crash:

The first crisis of production hit Venice in 1473, immediately following the extremely rapid take-off period. Production fell to half the peak of 1471–72, and eight of the dozen printers working in the city were driven from the market.

The problem was (as with many new technologies) that the market hadn’t yet been created. Customers had to be trained for print. You need widespread education to create a mass audience for books.

In particular the market was glutted with editions of classical texts, including multiple editions of works for which there were simply, as yet, insufficient readers.

Pettegree also says that consumers had to be re-trained out of manuscript-era buying habits. Most people were used to the idea that if you wanted a book you first had to know what book it was you wanted. Then you had to commission that book to be written out for you by a local scribe. The idea you might browse a bookshop and end up purchasing a book you never knew you wanted, or perhaps had never even heard of, was quite alien.

There were also complaints about quality. Many printed books looked terribly shoddy compared to manuscripts:

The first printed books could not live up to the standard set by manuscript production in Italy. They were often dirty, smudged and inaccurate. They included too many mistakes. The inefficiency and carelessness of printers would be a repeated lament of authors throughout the era of hand-press printing, but in this first generation it had a philosophical edge: the charge that print had debased the book.

Eventually people learned to deal with less beautiful books and came to love access to myriad cheap texts. I pessimistically wonder whether we might one day look back at the arrival of AI content in this way. Those of us raised in the age of beautiful hand-made texts and images find the machine-generated “slop” alternatives intolerably ugly and shoddy. But perhaps generations after us won’t mind about the carelessness and inaccuracies.

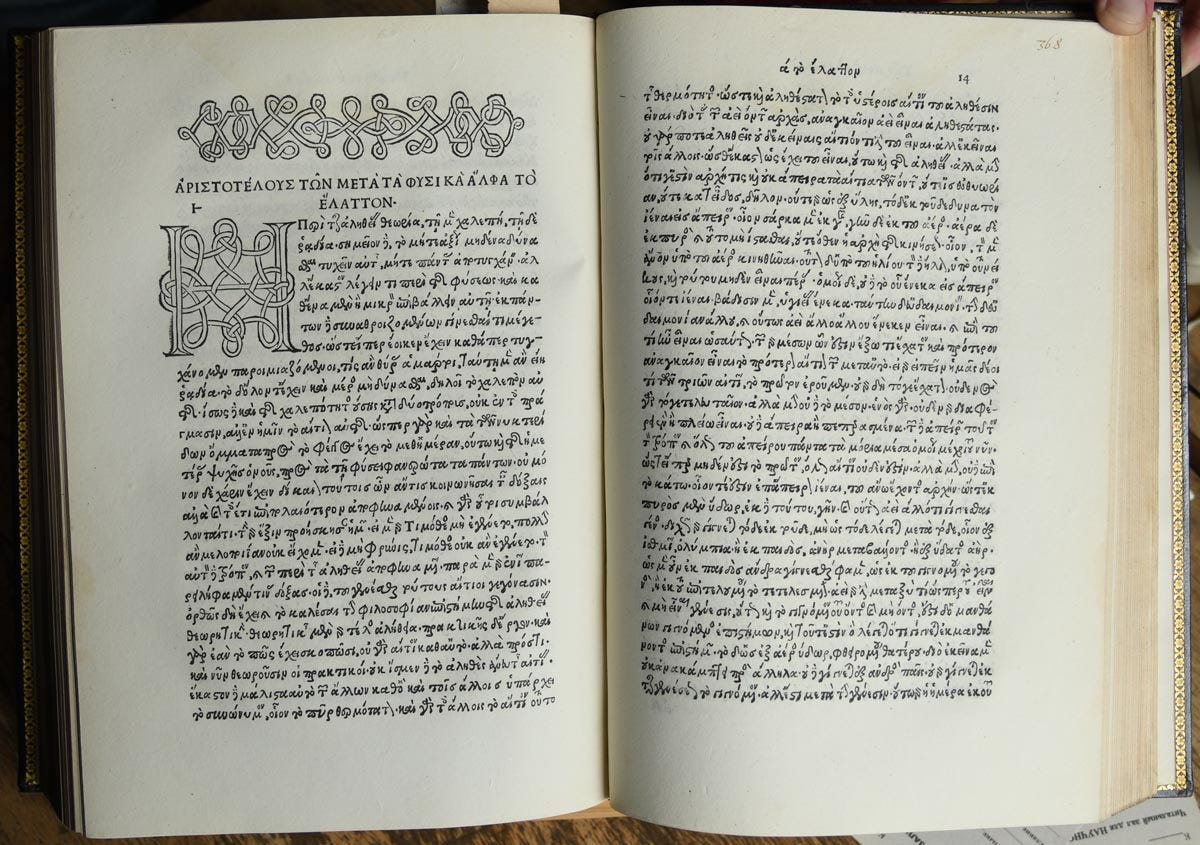

Not all early printed books were bad, of course. I love the beautiful clean printing of Aldus Manutius in Venice — the famous Aldine editions. Back in my antiquarian bookselling days I was lucky to handle a couple of these:

....MUCH MORE

And on the spread of the technology, a repost from July 29, 2018, "Despite the far-reaching consequences of Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press, much about the man remains a mystery, buried deep beneath layers of Mainz history":

One of my all-time favorite maps:

That's it. Mainz.

The rest of the series are after the jump. This one is via Economists View, we have the source below....

*****

An interesting paper from VoxEU.org February 11, 2011:

Information technology and economic change: The impact of the printing press

HT: economistsview