From The New Atlantis, Winter 2025 edition:

There’s no time like the present to revisit the warning of forgotten media theorist Harold Innis: “Enormous improvements in communication have made understanding more difficult.”

The owl of Minerva begins its flight only with the falling of dusk.

On the evening of May 25, 1947, the fellows of the Royal Society of Canada — the country’s leading scientists, artists, and intellectuals — gathered at the Chateau Frontenac in Quebec City for a much-anticipated event: an address by the society’s president, Harold Adams Innis. Innis was at the time a renowned academic in Canada and one of the most prominent political economists in the world. Through a series of expansive, meticulously researched books and articles tracing the development of basic Canadian industries — rail transport, fur trading, fishing, timber, paper — he had shaped his country’s understanding not only of its economy but of its history and culture. The assembled dignitaries were eager to hear where the great scholar would take his work next. But the talk, entitled “Minerva’s Owl,” fell flat. A tedious, convoluted disquisition on knowledge and communication, seemingly disconnected from Innis’s earlier work, it left the audience baffled and disappointed.

It wasn’t until four years later, when the lecture was published as the opening chapter of Innis’s book The Bias of Communication, that it began to attract interest. Although it remained a challenging and often frustrating work in its written form, “Minerva’s Owl” was also, for patient readers, a revelatory one. It made clear that Innis was engaged in a far-reaching exploration of the role of communication systems in shaping societies and their destinies. Drawing on examples ranging across the ages, from the etching of cuneiform characters on clay tablets in ancient Mesopotamia to the use of radio as a propaganda tool in the years leading up to the Second World War, he explained how the arrival of a new communication medium often triggers “cultural disturbances” that alter the course of history. Media are much more than channels of information. They’re instruments of political influence and imperial power, sculptors of civilization.

With its emphasis on media’s formative role in a society’s development, “Minerva’s Owl” would come to be seen as a founding document — maybe the founding document — of the academic discipline of media studies that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century. In 1964, the celebrated media savant Marshall McLuhan, who like Innis was a professor at the University of Toronto, wrote that he saw his own recent book, The Gutenberg Galaxy, as “a footnote to the observations of Innis.” The distinguished American educator and media theorist James Carey called Innis’s work “the great achievement in communications on this continent.”

Innis would not live to hear such praise. In 1952, the year after publication of The Bias of Communication, he died of prostate cancer, just fifty-eight years old. Unlike McLuhan, whose provocative work maintains a cultural currency, Innis and his more esoteric musings are today unknown to the general public. His name is rarely heard outside academic offices, conferences, and journals. But his ideas deserve a fresh look. Even though he died before he was able to complete his study of communication and civilization, his writings from seventy-five years ago shed an unexpectedly clear light on the media-induced cultural disturbances that trouble us today.

‘Ruthless Destruction of Permanence’

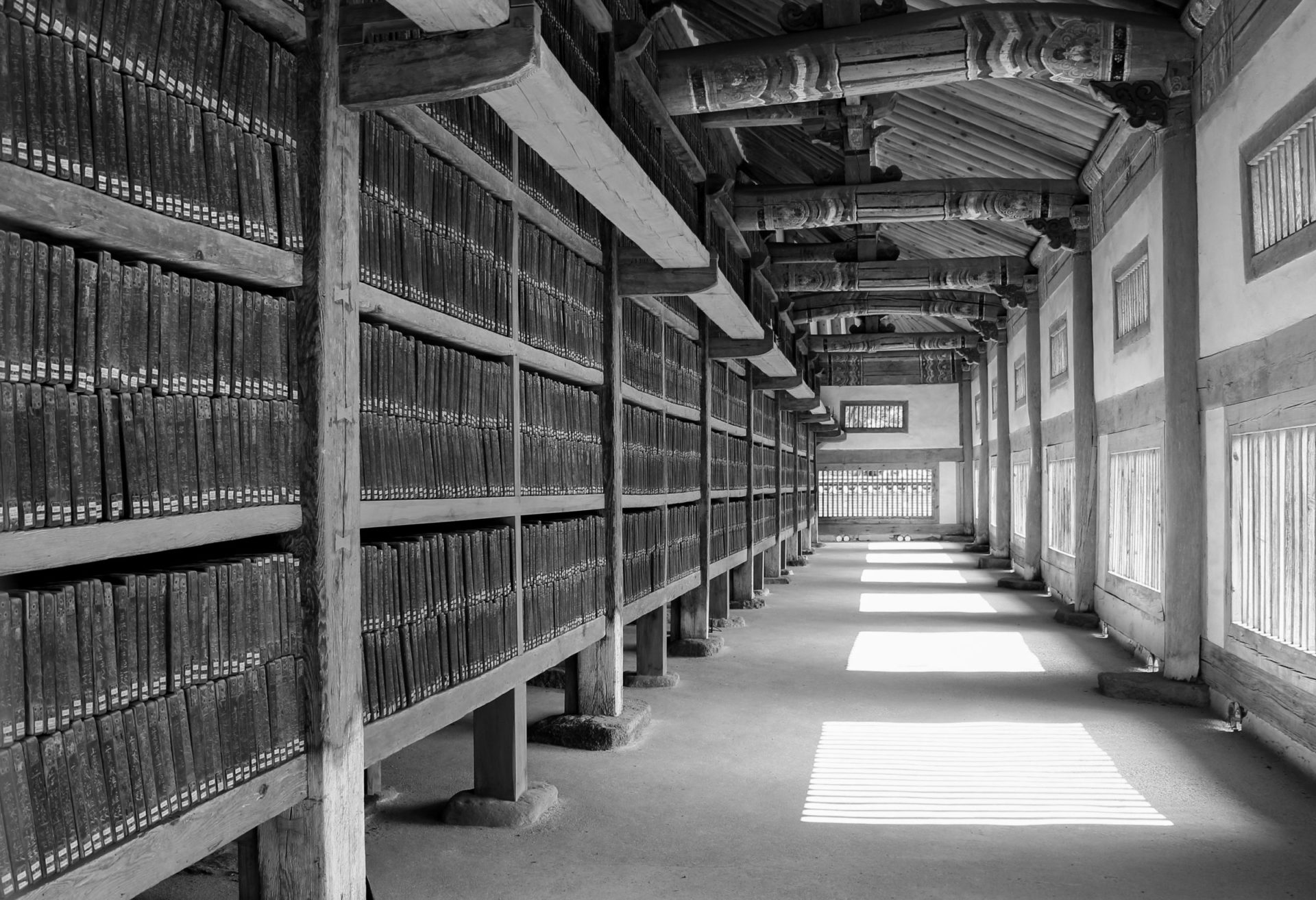

Communication systems are also transportation systems. Each medium carries information from here to there, whether in the form of thoughts and opinions, commands and decrees, or artworks and entertainments.What Innis saw is that some media are particularly good at transporting information across space, while others are particularly good at transporting it through time. Some are space-biased while others are time-biased. Each medium’s temporal or spatial emphasis stems from its material qualities. Time-biased media tend to be heavy and durable. They last a long time, but they are not easy to move around. Think of a gravestone carved out of granite or marble. Its message can remain legible for centuries, but only those who visit the cemetery are able to read it. Space-biased media tend to be lightweight and portable. They’re easy to carry, but they decay or degrade quickly. Think of a newspaper printed on cheap, thin stock. It can be distributed in the morning to a large, widely dispersed readership, but by evening it’s in the trash.

onto 81,258 wooden blocks in the thirteenth century, in a photo from 2022

Bernard Gagnon / Wikimedia

Because every society organizes and sustains itself through acts of communication, the material biases of media do more than determine how long messages last or how far they reach. They play an important role in shaping a society’s size, form, and character — and ultimately its fate. As the sociologist Andrew Wernick explained in a 1999 essay on Innis, “The portability of media influences the extent, and the durability of media the longevity, of empires, institutions, and cultures.”....

....MUCH MORE

A quick search of the blog for 'Innes' returns only one hit: U.K.: Green pressure grows for cow flatulence tax which probably isn't related.

"The Oracle of Mass Media: Remembering Marshall McLuhan"

Sometimes I think McLuhan could see the future: