From ZeroHedge, September 26:

A theme that shapes the way I look at the world is turmoil anywhere begins with a problem in – and ends with a solution for – U.S. Treasuries. It’s not lost on anyone how grossly boring and tirelessly dry a subject it can be to read about, but, at the end of the day, sh*t won’t hit the fan until Treasuries sh*t the bed.

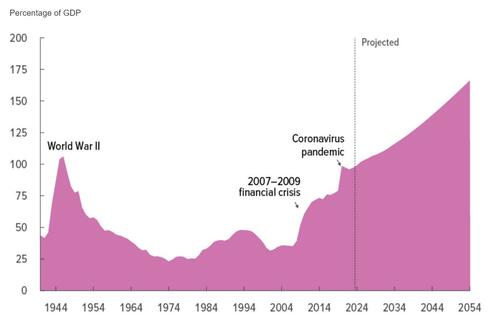

Not unique to the Treasury market is that, to function properly, it requires a marginal buyer providing adequate demand. Rates can remain stable in the face of massive debt issuance as long as there is a steady group of buyers able and willing to digest it; otherwise, there can be historic volatility as the market looks for a new one.

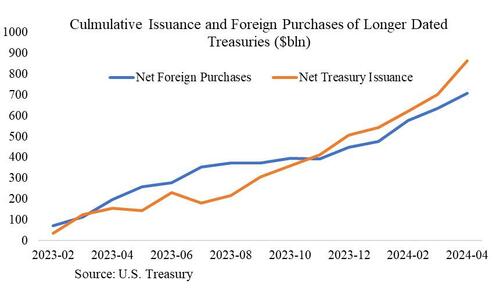

The Fed and commercial banks had this role during and after Covid, but the expiration of pandemic rule changes that armed the banks with war-time balance sheets forced them to reduce holdings, and the Fed began selling in mid-2022. They were replaced by onshore hedge funds in late 2022 through 2023. As I showed last month, offshore hedge funds have surprisingly helped absorb much of the debt tsunami the last couple years:

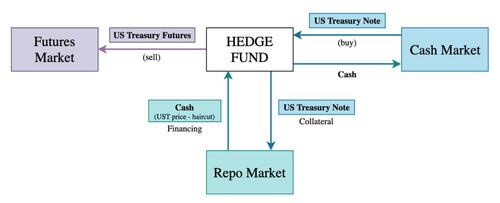

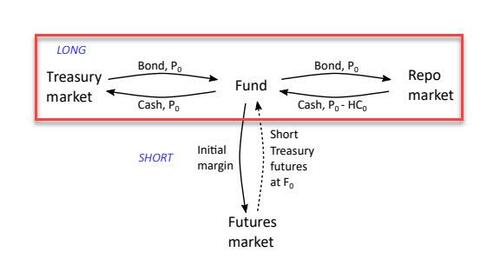

The “Treasury market” is divided into three major sub-components: the one for outright purchases and sales of Treasuries, the cash Treasury market (or ‘the secondary market’); for borrowing cash secured against Treasury collateral, the Treasury repo market; and for derivatives on Treasuries, the Treasury futures market. All three must be stable for the broader market to be functional.

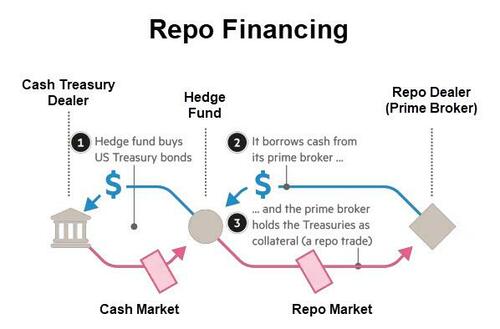

Below is an example of a hedge fund interacting with all three as part of the cash-futures basis trade (a.k.a., “the most important trade on Earth”), by shorting the Treasury futures, buying the cash Treasury, and using 50x or more leverage in the repo market to turn a tiny mispricing between the two into a worthwhile profit:

But first, some context.

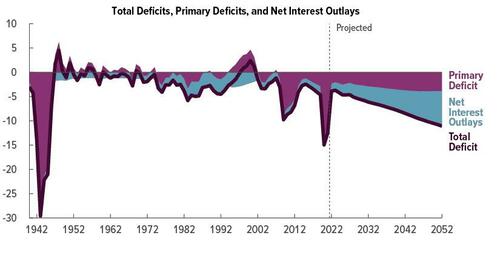

In November 2021, just before the Fed stepped away from supporting it after nearly two years, the Treasury’s “surveillance group” explored five "workstreams" to strengthen the bond market’s resilience in response to then-recent stresses. There was nothing to prevent a March 2020 redux, especially with the Fed about to not only stop buying but become a net seller, and Washington of course having no plan to “normalize” its borrowing:

In other words, on the verge of the marginal buyer leaving the market to face a bond deluge by itself, officials tried to prevent an inevitable trainwreck.

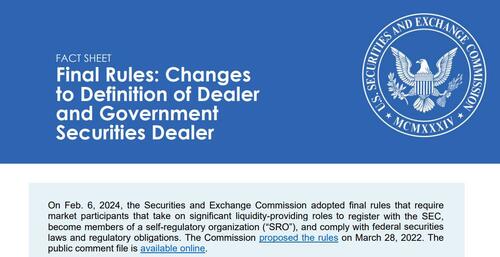

The "five workstreams" boil down to two changes. The first is “greater transparency and data availability”, hence the SEC's February decision forcing Treasury cash market participants "acting on their own account" and managing at least $50 million to register as dealers (ZeroHedge did a good job covering the decision in "SEC Cracks Down On Basis Trades, Will Force Top Hedge Funds To Register As Dealers, Resulting In Collapsing Treasury Market Liquidity"):

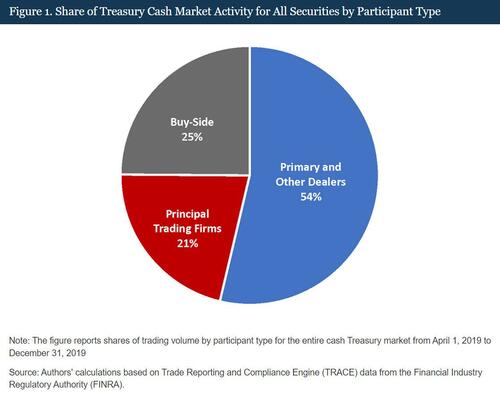

The “Dealer Requirement” targets principal trading firms (PTFs), whose strategy is to profit from small intraday mispricings. These PTFs account for 20% of cash market volumes (which is enough to be labeled “de facto market makers”) but unlike a marginal buyer, they disappear when volatility picks up, so their provision of liquidity is illusory. They are just very active in the cash market.

Time will tell if it’s a Dealer Requirement that leaves the Treasury market in dire straits as PTFs depart to chase profits elsewhere, but I would guess it won't be as impactful on its own.

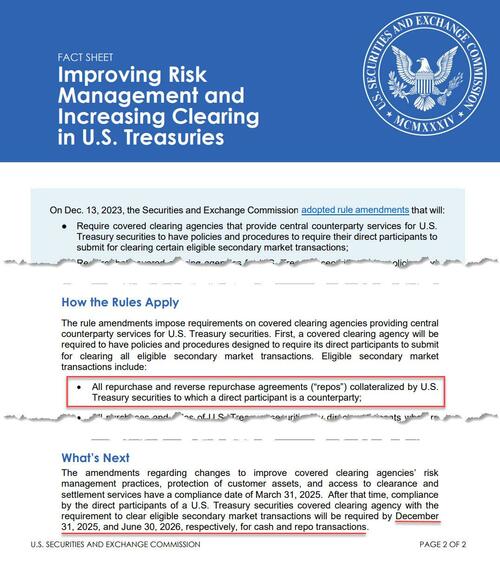

The second, and much more meaningful, change is to “improve the risk management and settlement” of the Treasury market, by mandating all Treasury repos be centrally cleared by June 2026:

All else being equal, central clearing does better manage systemic risks, but at the expense of higher trade costs, which means a lot for the hedge fund trades that power the Treasury market machine.

In a ZeroHedge article from last month, I noted that only a handful of hedge fund arbitrage trades, especially cash-futures basis trades, are responsible for “greasing” the Treasury market – that is, providing the liquidity for some deeply unpopular bonds that would otherwise prove very difficult to sell, helping to stabilize yields and keep the wheels on the cart amid the tidal wave of issuance and “War Finance” that even highly politicized officials can agree has no end in sight:

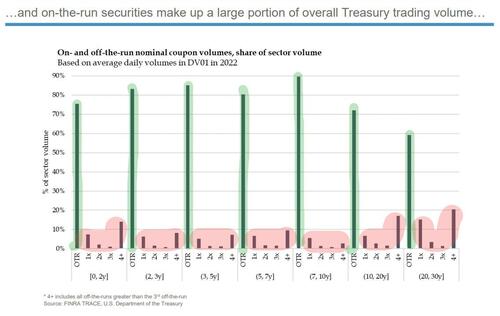

That’s because going “long the basis” – which is the most common implementation of a basis trade – usually means buying a formerly-issued and illiquid (“deeply unpopular”) cash Treasury as part of it.

A Treasury bond, such as a 7-year note, is considered "on-the-run" (OTR) from the time it is auctioned until the next issuance of a 7-year note at a subsequent auction (usually a month or two later). Once the new 7-year note is issued, the previous note becomes "off-the-run" (OFR). The term "first off-the-run" (1x OFR) refers to the note that was most recently replaced by a new on-the-run issue.

As the chart below shows, on-the-runs (in green) are much more liquid and frequently traded than the “deeply unpopular” off-the-runs (in red). Hedge funds buy off-the-runs because they're cheapest when it comes to actually fulfilling the futures' obligation to deliver a security (in this case, a Treasury security).

The trade has been around for decades but – maybe incidentally – it’s safe to say that when it comes to providing Treasury liquidity, its role is becoming less of a feature and more of a necessity.

Which is why it's worth looking at.

But key to this trade being worthwhile is having enough access to leverage, and sometimes extraordinary levels of it. That’s because the actual basis – the difference between the cash Treasury and Treasury futures price – is tiny, and unlevered would not be worth harvesting. The leverage is accessed because most of the cash Treasury is financed in the repo market.

The three steps in the diagram below occur simultaneously:

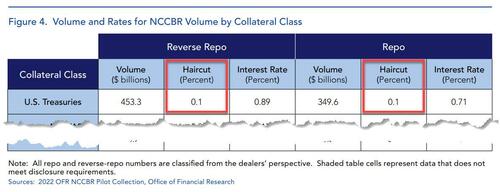

Repo dealers determine how much leverage their hedge fund customers will have access to by assessing the trade’s risk profile – the fund’s history, the duration of the repo loan, the current level of volatility, etc. This means charging the customer a “haircut” — i.e., a premium equal to a small percentage of the trade that is not covered by the repo loan. The haircut protects the repo dealer against decreases in the value of the Treasury collateral in case there is, for some reason, a fire sale of Treasuries.

For example, if a hedge fund wants to purchase a Treasury worth $100 but the dealer will only loan $98 for the collateral, then the fund must provide for the remaining $2 out of its own capital to make the purchase. The $2 is a 2% haircut (‘HC’ in the image below; the repo financing is outlined in red):

Instead of a 2% haircut requiring the fund to post $2, say it's only 1%, and the repo loan covers the other $99 – the fund can now, with its $2, use twice the leverage as it could with the 2% haircut. The same $2 in capital can now purchase twice as many Treasuries, or $200 in collateral. This would also mean that it can yield the same return as before if the basis is only half as wide.

The point here is that it’s the haircut which attracts hedge funds to buy Treasuries, because a smaller haircut means greater leverage, and more leverage means more profit. The trade would become so popular and competition among repo dealers so intense that “zero haircuts” became the standard:

And in case the math doesn’t seem to add up because zero haircuts would somehow mean infinite leverage, you’d be correct. Don’t take it from me – this is directly from the Fed:

“…hedge funds in the aggregate were effectively leveraged 56-to-1 on their Treasury repo trades, though individual funds facing zero haircuts did not require any capital to support their repo borrowing and were effectively infinitely leveraged on these trades.”

....MUCH MORE

If one is so inclined the earlier (August 31) article may be of interest:

How the Most Important Trade on Earth Falls Apart