A luxury penthouse flat has apparently been named after one of history's most famous communists.

The £2.5m apartment in Deansgate, Manchester, bears the name The Engels, in an apparent reference to philosopher and revolutionary Friedrich Engels, who, along with Karl Marx, wrote The Communist Manifesto.

A tenants group said it was ridiculous to name an expensive flat after a man who at one time wrote extensively about poverty and squalor in Manchester.

The developer, Renaker, has been contacted for comment.

'Inescapable irony'"It is absolutely ridiculous," said Isaac Rose, of Greater Manchester Tenants' Union.

He said people in Manchester and Salford, where the German-born philosopher and writer lived at one stage of his life, suffered from a shortage of affordable accommodation.

Mr Rose added: "Engels wrote about a divided Manchester and we seem to be still there."

The Engels is in a building a short distance from where he researched his influential work, The Condition Of The Working Class In England.

He had met Karl Marx in 1844, and the pair founded The Communist League.

While Engels wrote about poverty, he hailed from a wealthy family.His father owned a textile mill in Barmen in Germany, and it was his father's hope that by sending him to work in the family's textile mill in Weaste, Salford, Engels would recant his radical ideals....

....MUCH MORE

When “Cottonopolis” Was One of the Ten Largest Cities on the Planet: Manchester After Engels

Or something

See after the jump if interested.

From Places Journal, June 2020:

Manchester After Engels

Manchester is, to say the least, an enigma. Ever since the 2016 referendum on membership of the European Union, the United Kingdom has been languishing in Brexit limbo, investment confidence has been flagging, and everyone has been fretting about the future. The North of England, where a majority voted to Leave, has long been notoriously, pathologically depressed, its cities and towns, one after another, the victims of postwar post-industrial decline and post-millennial austerity. So how to explain the recent show of confidence in the self-styled capital of the North?

Manchester, whose collapse in the mid 20th century rivaled that of Detroit, is busily, loudly rebounding; the city is now constructing a cluster of skyscrapers on the edge of its downtown core, the scale of which dwarfs all existing buildings. 1 Not all that long ago, a big building here could perhaps boast 100,000 square feet; today “big” means half a million. The new South Tower of Deansgate Square, a collection of mostly residential towers, rises priapically to more than 600 feet, and it might soon be overtaken by the 700-foot-tall Trinity Islands. There were at the end of last year an unprecedented 80 construction sites in the city center, including 14,000 future apartments, many of which are underwritten by international investment. This is proving to be the most thoroughgoing transformation of an English city for some time; indeed, one of the great spectacles of contemporary Britain. “Manchester is visibly booming,” wrote Oliver Wainwright, the architectural critic of the Guardian. “Cranes cluster across the skyline and the concrete liftshafts of future towers dot every corner. The city is even beginning to look drunk on its own success.” 2

Inevitably this is a local story, one that underscores much about the unpredictability and uncertainty of Britain as it finally leaves the European Union, a departure that was expedited by the Conservative party’s victory in the recent general election. Yet it is also a global story; a story about how a city that was at the center of the industrial revolution, and that shaped global capitalism in the 19th century, is today being reshaped by post-industrial globalized capital. As the geographers Jamie Peck and Kevin Ward put it in 2002, in a prescient book on the beginning of the contemporary boom: “Being first proved to be a double-edged sword. The first industrial city was the first to experience large-scale deindustrialization. … Once a global player, the city is in many ways now just another potential investment site in the global economic system.” 3 And now, as I write, the future of the global economic system has been put on at least temporary hold by the spread of a global pandemic; the partly constructed new skyline of Manchester now constitutes an unwitting memorial to the moment the city went into lockdown.

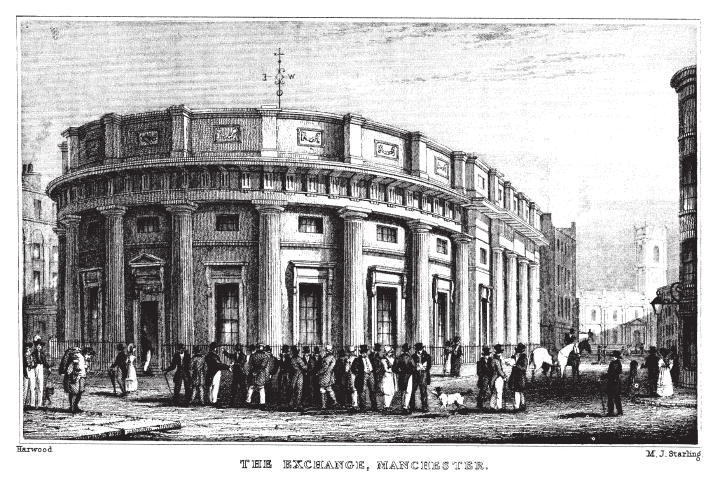

It can feel remarkable to recall that Manchester, in 1900, was one of the ten largest cities on the planet, with a greater metropolitan population just shy of two million. From a market town of about 40,000 in the late 18th century, the city had grown, over the course of the 19th, into an industrial dynamo, the world center of textile manufacturing and trading, home to so many mills that it became known as “cottonopolis.” “It was the principal site of what was rapidly coming to be thought of as the Industrial Revolution,” wrote the cultural historian Steven Marcus, “and was widely regarded as the ur-scene, concentrated specimen, and paradigm of what such a revolution was portending both for good and bad.” 4 In this light it bears remembering that Manchester was at once deeply enmeshed in the Atlantic slave trade of the late 18th century and later one of the centers of the abolition movement in England. 5

"The Cotton Bond Bubble" or How the Confederacy Might Have Won the Civil War

Hey, Hey, Ho, Ho, Marx and Engels Got To Go!

....Because that story reminded me that Friedrich Engels' fortune was built on the cheap cotton produced by American slaves via the family's business Ermen and Engels. In fact 'ol Freddie spent a lot of time in Manchester representing the fam at one of their cotton thread factories and seemed okey-dokey with the fruits of the slave biz even while decrying the condition of the Manchester laborers.

And Marx suckled on the teat of that cash flow to support himself..

When he wasn't speculating in British equities. See:

Karl Marx Dabbles in the Market (and rationalizes his success)The Karl Marx Credit Card – When You’re Short of Kapital

Friedrich Engels: Global Macro With an Emphasis on Commodities

Karl Marx on Market Manias

Marx and Engels Meet The Jetsons

On Marx and "The Law of the Tendency of the Rate of Profit to Fall"

Here's the amusingly numbered Ch. 13 of Volume III, Das Kapital via Marxists.org.

I've never gotten much farther than Volume I, the first chapter of which is 'Commodities'.

There are Some Things Money Can’t Buy. Especially If You Abolish All Private Property.

As the Civil War raged in North America the working people of Manchester sided with the enslaved Black people* but the capitalists like Engels and by extension Marx, wanted that cheap cotton to keep flowing.

That's a bit of history for this 157th anniversary of the beginning of the Battle of Gettysburg.

More tomorrow. [coming up on the 161st anniversary of the great battle]

*If interested see The Guardian, February 4, 2013:

Lincoln's great debt to Manchester