From The Milken Institute Review, October 31:

Most governments maintain their own lists of the minerals they categorize as “critical,” which are usually put together by committees of scientists and engineers. Among the best known: the European Union’s list of Critical Raw Materials and the U.S. Geological Survey’s List of Critical Minerals. Canada and Australia also have their own, but they serve somewhat different purposes because they are linked to their strong domestic mining industries. Canada’s list focuses on helping partners and allies dependent on its exports, while Australia’s takes note of the need to “leverage growing global demand” — since many industrial powers (notably the U.S.) have neglected their mining industries.

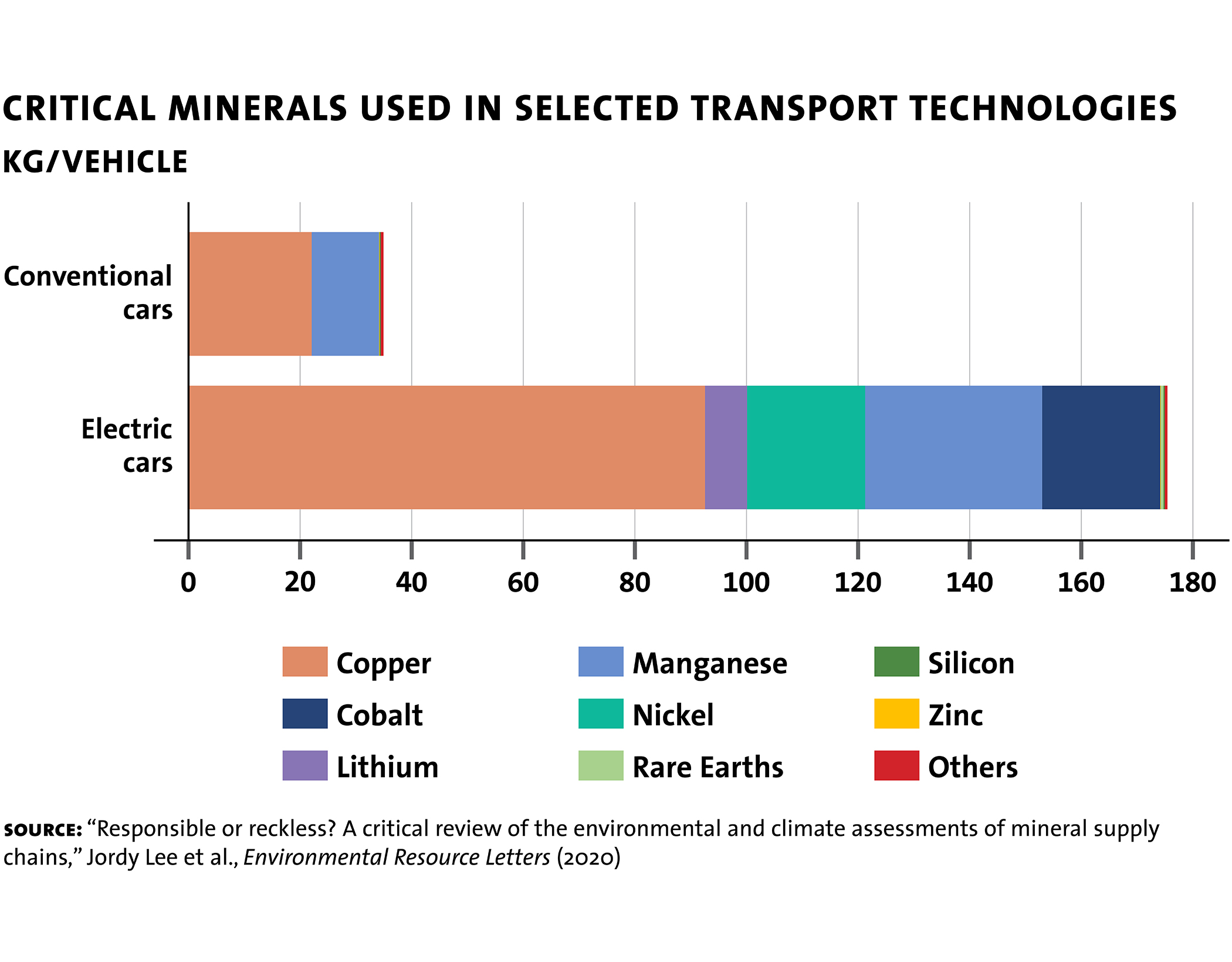

However, what started out as compilations to inform policy and sustain economic efficiency has in recent years morphed into lists that are central to geopolitical strategy. For one thing, some of these minerals are as tightly bound to energy technologies in the 21st century as fossil fuels were in the 20th century. Electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar panels and batteries (among other technologies) are central to the net-zero transition and are all heavily dependent on critical minerals.

This alone wouldn’t be such a problem if the demand for many of them wasn’t expected to grow ten-fold in the foreseeable future. Or if the United States (and other governments) hadn’t spent decades inadvertently crippling its own ability to mine and refine these minerals. Indeed, over the next few years, the world is facing shortages that will at best undermine productivity growth and at worst exacerbate the tensions of a new type of Cold War.

In critical minerals, as in baseball, ya can’t tell the players without a scorecard. Many of them have unpronounceable names seemingly straight from Star Trek, including ytterbium (not to be confused with yttrium) and europium (which is almost exclusively produced in China). Their uses range from making stainless steel harder and tougher (chromium) to helping to control nuclear reactors (yes, europium) and making batteries last longer in electric vehicles (cobalt). And while the recipes typically don’t call for much of them, they are very difficult to work around in manufacturing. Indeed, many are considered critical because substitutes either don’t exist or are incredibly expensive.This isn’t to say that Tesla would go out of business if supplies of cobalt vanished. But without it, the current generation of electric vehicles would not be able to drive as far between charges or remain in service as long without replacing the batteries. Cobalt shortages might also jack up the cost of producing e-vehicles sufficiently to delay the day they can compete in economic terms with your father’s Grand Cherokee. This is also why Tesla is always trying new battery cells in the different types of cars it produces — relying on cobalt for your entire business model is risky.

Consider, too, that since cobalt lengthens battery life, a lack of it could exacerbate environmental problems around recycling or disposing of the batteries. Then, there’s the damage to vulnerable groups: cobalt shortages might further incentivize risky mining operations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where hundreds of thousands of Congolese and as many as 40,000 children already work in hazardous conditions. As cobalt prices increase and as demand grows, many groups might stop asking questions about where their cobalt is coming from.

Really ComplicatedOften, the production of a critical mineral is problematic to scale up. For larger mining and metals companies, it may not be worth investing millions in the technology, equipment and expertise to produce minerals for niche markets when copper, iron or even gold can provide steady, reliable revenues. Environmental concerns also require producers to run a gauntlet of protocols before they can even consider opening a mine in many countries. Moreover, people living in the U.S. and other tech-focused economies often have very negative opinions of the mining industry despite relying on critical minerals the most. This makes it hard to incentivize critical mineral production or investment....