Buying Tomorrow

....MUCH MOREWhen the rest of the world are mad, we must imitate them in some measure.It would be fair to guess that Charles Prince’s echo of John Martin, a banker who was nearly ruined by the South Sea Bubble, reflects a sincerity that was blissfully ignorant rather than an irony that wasn’t. One might even be willing to bet on it—if, that is, certain information about Prince’s knowledge and state of mind were actually forthcoming. A wager entails uncertainty, but without the prospect of a future event coming to pass, uncertainty is worth little besides the mystery it affords.

—John Martin, Martin’s Bank, 1720

As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.

—Charles Prince, Citigroup, 2007

To cast lots for Christ’s robe, as Pontius Pilate’s soldiers did, was to play a game of chance. Gambling is one of those activities, along with religious worship and prostitution, that was popular already by the time any recording of history began. Our modern financial system owes much to this desire to make a fortune off of Fortune, though a society that organizes itself around financial risk-taking, whose national assets oscillate in an invisible cloud of ones and zeros, requires a very particular understanding of what the future can hold. Finance makes a commodity out of expectation, something to be bought (preferably low) and sold (preferably high). In the case of the worried farmer or the worried breadwinner, the future can also be viewed with suspicion, but finance enables the anxious to trade one possibility for another: both the speculator and the hedger are seeking the best future that money can buy.

As much as the old saw about money and happiness gets deployed by the usual suspects—grandmothers, clergymen, credit-card commercials—there seems to be some confusion in this country over which one is the legitimate object for pursuit. If anything, the optimistic strain that runs through American history has been a boon to the financial industry, which has literally capitalized on the belief that in the future lies prosperity. Technology has made it possible for finance to transcend the limits of the material world: so much money changing invisible hands has long since become the stuff of American dreams. And for the Chicken Littles who equate the future with decline and decrepitude, financiers found a way to make money for them (and, naturally, from them), too. Insurance for those who don’t want to lose, and short-selling for those who still want to win.

But the future was not always so amenable to our business plans. As long as the future belonged to the gods, there was little arguing with the inevitability of fate. Despite his parents’ deployment of the ultimate avoidance strategy—tie baby’s ankles together; order servant to abandon baby on mountainside—Oedipus killed his father anyway. In Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk, Peter Bernstein points out that the future had to be something other than “the murky domain of oracles and soothsayers” before it could be put “in the service of the present.”

Bernstein makes much of the distinction between “uncertainty” (vague, amorphous) and “risk” (precise, quantifiable). The story he tells is a march of progress, from haplessness to sophistication. The word “risk” comes from risicare, early Italian for “to dare”: one asserts a choice rather than submits to fate. By changing humanity’s relationship to God and nature, the Renaissance and the Reformation filled the future with possibility and promise. Renaissance gamblers were especially motivated to slice up the future into probable outcomes, calculating the odds of each and betting accordingly. The Chevalier de Méré, a seventeenth-century French nobleman with a penchant for gaming, boasted in a letter to Blaise Pascal that he had “discovered in mathematics things so rare that the most learned of ancient times have never thought of them and by which the best mathematicians in Europe have been surprised.” De Méré had figured out that the probability of throwing a six with four throws of one die was slightly more than 50 percent (51.77469136 percent, to be exact), and so he would throw the die many times and win small amounts, instead of hoping for a windfall—and hazarding ruin—by betting on a few chance throws.

For contemporary poker players, the parallel to De Méré’s strategy is known as “grinding,” as in grinding out a profit over an extended period of time. The strategy might also sound familiar to the common investor. Since the 1970s, when Burton Malkiel wrote about the “random walk” of an “efficient market” that was hard for even the experts to time or to beat, investors have been told to diversify (finance speak for “Don’t put your eggs in one basket”), and to buy and hold: in the long run, you should come out ahead. (A whole industry of indexed mutual funds proliferated as a result.) Of course, this advice assumes that the chance your portfolio will grow is as measurable as the chance De Méré’s die will turn up six. And it also assumes that “the long run” will be shorter than your lifetime—which, as John Maynard Keynes remarked, is far from guaranteed....

A few prior mentions of Peter Bernstein. first up, April 28, 2008 (note the date):

One Guy Who Has Seen It All Doesn't Like What He Sees Now

Peter Bernstein has witnessed just about every financial crisis of the past century.As a boy, he watched his father, a money manager, navigate the Depression. As a financial manager, consultant and financial historian, he personally dealt with the recession of 1958, the bear markets of the 1970s, the 1987 crash, the savings-and-loan crisis of the late 1980s and the 2000-2002 bear market that followed the tech-stock bubble.......WSJ: Aside from securitization, what were the main causes of the problem?

Mr. Bernstein: You don't get into a mess without too much borrowing. It was sparked primarily by the hedge funds, which were both unregulated by government and in many ways unregulated by their owners, who gave their managers a very broad set of marching orders. It was a real delusion. It was like [former New York Gov. Eliot] Spitzer: "I am doing something dangerous, but because of who I am, and how smart I am, it is not going to come back to haunt me."When you think about how all of this will work out in the long run, we are going to have an extremely risk-averse economy for a long time. The lesson has painfully been learned. That's part of the problem going forward. You don't have a high-growth exit from this, as you've had from other kinds of crises. We won't have a powerful start, where the business cycle looks like a V. Here, the shape of the business cycle is like an L, where it goes down and doesn't turn up. Or like a U, a flat U. The reason for that is that people aren't going to get caught in this bind again. They will tell themselves, "I'm too smart to do that again." And everyone else is going to be saying the same thing. It is, in fact, going to be a wonderful environment in which to take risk, because there aren't going to be any excesses....MORE

May 5, 2008

I said earlier today, in "Will Green Investors Demand Higher Risk Premia?" that the short answer was yes and that I would expand (expound) on this idea. First though, it might be useful to link to a couple old pros, Robert Arnott and Peter Bernstein. If you know this stuff, this is a good brush-up, if you don't, this is a very readable 22 page PDF.

The goal of this article is an estimate of the objective forward-looking U.S. equity risk premium relative to bonds through history—specifically, since 1802. For correct evaluation, such a complex topic requires several careful steps: To gauge the risk premium for stocks relative to bonds, we need an expected real stock return and an expected real bond return. To gauge the expected real bond return, we need both bond yields and an estimate of expected inflation through history. To gauge the expected real stock return, we need both stock dividend yields and an estimate of expected real dividend growth. Accordingly, we go through each of these steps. We demonstrate that the long-term forward-looking risk premium is nowhere near the level of the past; today, it may well be near zero, perhaps even negative....

June 5, 2018

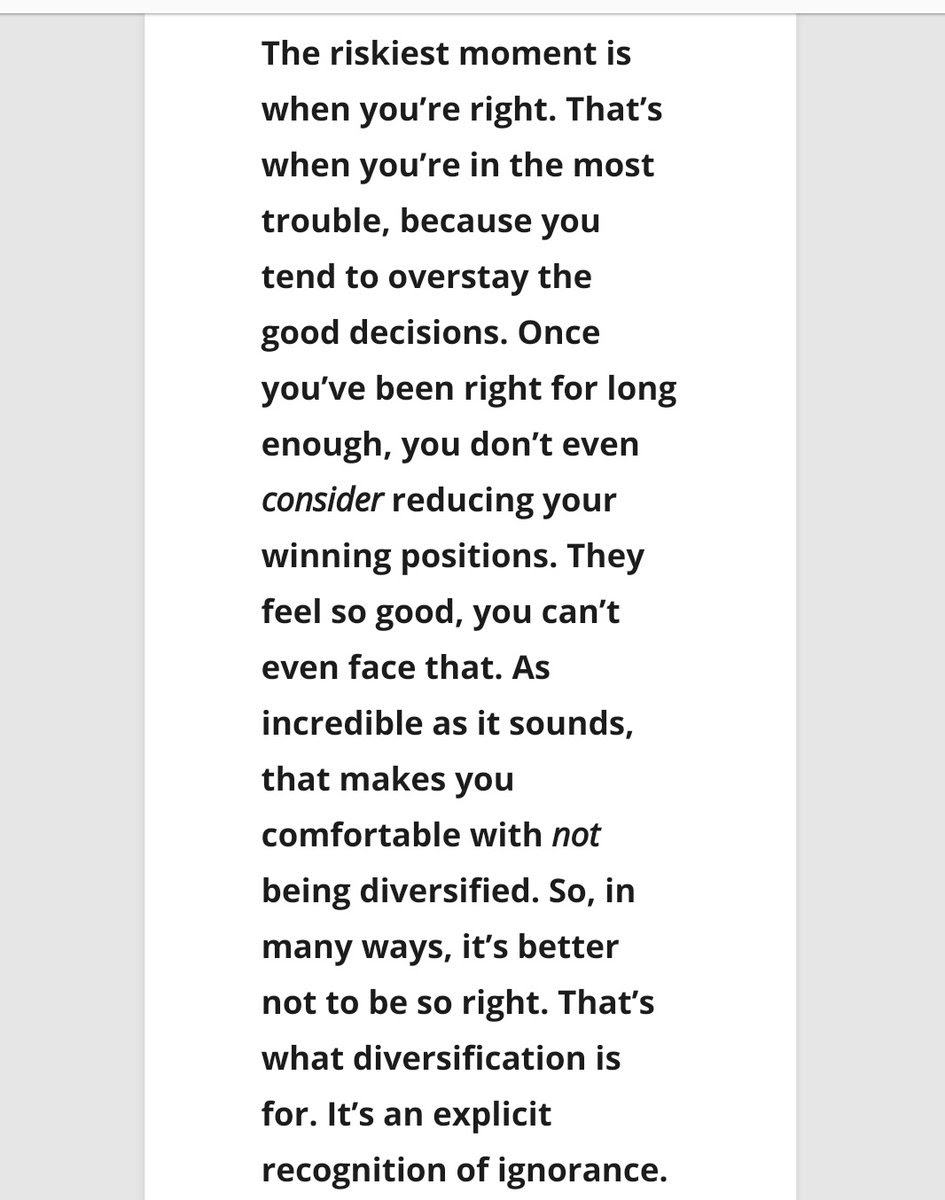

"When is risk the highest?"

When is risk the highest?

Hat Tip: Vetri Subramaniam

Also at Alpha Ideas:

Weekend Mega Linkfest: June 30, 2018