There is a lot, a lot, of information here, the authors are showing off CBI's analytical chops.

From CB Insights:

The 7 Industries Amazon Could Disrupt Next

Since 1999, Amazon's disruptive bravado has made “getting Amazoned” a fear for executives in any sector the tech giant sets its sights on. Here are the industries that could be under threat next.

Jeff Bezos once famously said, “Your margin is my opportunity.” Today, Amazon is finding opportunities in industries that would have been unthinkable for the company to attack even a few years ago.

Throughout the 2000s, Amazon’s e-commerce dominance paved a path of destruction through books, music, toys, sports, and a range of other retail verticals. Big box stores like Toys R’ Us, Sports Authority, and Barnes & Noble — some of which had thrived for more than a century — couldn’t compete with Amazon’s ability to combine uncommonly fast shipping with low prices.

Today, Amazon’s disruptive ambitions extend far beyond retail. With its expertise in complex supply chain logistics and competitive advantage in data collection, Amazon is attacking a whole host of new industries.

The tech giant has acquired a brick-and-mortar grocery chain, and it’s using its tech to simplify local delivery, such as machine vision-enabled assembly lines that can automatically sort ripe from unripe vegetables and fruit.

Last June, it acquired the online pharmacy service PillPack. Now, it’s building out a nationwide network of pharmacy licenses and distribution that could one day allow Prime users to receive their medications through Amazon.

On its own Amazon Marketplace, the company is using its sales and forecasting data to offer de-risked loans to Amazon merchants at better interest rates than the average bank.

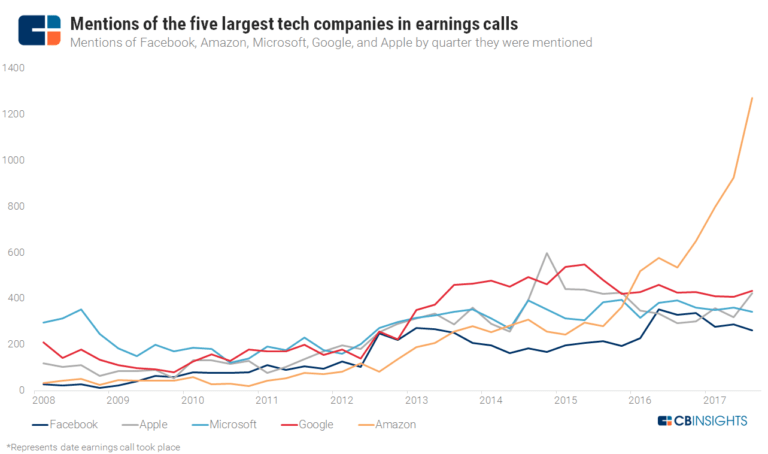

On calls with investors in 2018, executives of public American companies mentioned Amazon more often than they mentioned any other company, public or private. They mentioned Amazon more than they mentioned President Trump — and nearly as much as they mentioned taxes.

We researched the 4 industries where Amazon’s disruptive intentions are clearest today — pharmacies, small business lending, groceries, and payments — as well as 3 industries where Amazon’s efforts are more nascent. The disruptive possibilities in these industries — mortgages, home & garden, and insurance — remain speculative for now, but with Amazon’s scale and advantages, they could soon be a reality.

Below, we lay out the case and the progress that Amazon has made thus far.

Table of contents

The 4 industries Amazon will disrupt in the next 5 years

- The 4 industries Amazon will disrupt in the next 5 years

- The 3 industries Amazon could go after next

1. Pharmacies: Making drugs a low-margin commodity

Pharmacy chains like Walgreens and CVS have already seen their retail revenues suffer from the rise of Amazon’s convenient “everything store.” Today, they have a new challenge: in addition to disrupting their “front of store” Amazon is angling to disrupt their core business of drug distribution.

Amazon’s interest in disrupting the drugstore is decades old. In 1999, Amazon bought 40% of Drugstore.com (at the time, a pre-product and pre-revenue company). Bezos would later hire its CEO, Kal Raman, to run hardlines (retail products which are hard to the touch) at Amazon.

Amazon proceeded to lay low in the pharma space until 2016, when Amazon reportedly received its first licenses to sell pharmaceutical products and drugs from various state boards across the United States.

In 2018, Amazon made another move towards gaining footing in this notoriously complex and highly regulated space: it acquired PillPack in a deal worth around $750M.

Image source: AlphaStreet

Amazon’s acquisition of a $100M+ business with pharmacy licenses in all 50 states caused the tickers of Walgreens, CVS, and Rite-Aid to lose about $11B in value overnight — and represents Amazon’s first significant move not just against the major drug store chains, but against the powerful pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) that manage the dispensation of drugs for major employers, and others in the healthcare supply chain.

Why Amazon is going after pharma

When it comes to pharmaceuticals, there are several reasons that Amazon — and its direct-to-consumer model — could be a good fit in the industry.

Convenience: The process of filling a prescription at a typical brick-and-mortar pharmacy is — between getting there, limited opening hours, and waiting in line — often inefficient and time-consuming. Amazon’s model aims to limit the effort patients need to expend while also getting prescriptions to them within a day or two.

Customer experience: Complaints from users of specialty pharmacies about errors, delays, confusing policies, and poor customer service have been common for years. Amazon’s advantage here comes in its two decades of e-commerce logistics experience — this could help avoid delivery mistakes, a vital consideration for serving people with complex medication needs.

Partnerships: Amazon is working with holding company Berkshire Hathaway and investment bank JPMorgan on a healthcare venture known as Haven, which aims to streamline healthcare. While little has been made public about Haven’s strategy, court testimony from then COO Jack Stoddard stated that an initial goal is to “simplify health insurance.” With its own insurance offering, Amazon would have a potential launch pad to do the work of a traditional pharmacy benefit manager for the partnership’s combined 1.2M employees — and perhaps eventually the wider public.

Pre-existing customer base and distribution capabilities: CVS has announced an experiment in medication delivery, offering $4.99 for next-day delivery. But with 100M Prime subscribers — conditioned to expect free, fast delivery on virtually any good — Amazon will likely be placed to offer better distribution than CVS or other pharmacy chains.

Physical stores: When Amazon acquired Whole Foods in 2017, it also acquired around 450 physical locations where it could theoretically dispense prescriptions the same way that CVS and Rite Aid do. These stores could also serve as hubs for medication delivery via a service like Prime Now, similar to how Amazon offers same-day Whole Foods grocery delivery.

Amazon has also announced plans for a new grocery chain, separate from its acquisition of Whole Foods. These stores would be more like conventional grocers, and could contain pharmacies — either for in-store prescription pickup, or as hubs for a local delivery service.

Streamlined distribution: Amazon’s ambitions in pharmacy may not end at just delivering drugs.

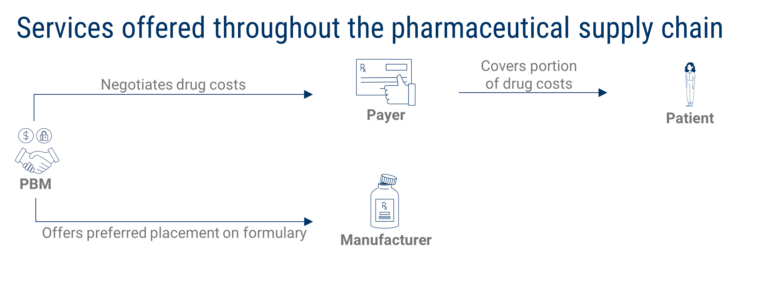

The pharmaceutical supply chain involves all kinds of middlemen, each of whom takes a slice of profit as drugs make their way from the manufacturer to the end-patient user — the kind of messy business model that Amazon has special expertise in disrupting.

In broad terms, patients pay pharmacies for drugs, which pay wholesalers, which in turn pay manufacturers or distributors.

But there are additional layers which make the supply chain more complex. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) negotiate with distributors and manufacturers for better prices on bulk drugs — a service they offer to payers (insurance companies). They also receive a copay from individual patients, and get paid by manufacturers to market their drugs to payers.

Among the different middlemen, PBMs make the lion’s share of the profit from your typical drug transaction. On the sale of a drug with a sticker price of $100, the profit breakdown is roughly:

Virtually every insurance provider outsources its drug procurement to a pharmacy benefit manager. Most major employers use PBMs as well, in their case to help negotiate for better rates on drugs for their employees.

- Wholesaler: $1.00

- Pharmacy: $5.00

- PBM: $6.00

PBM’s core advantage is that they collect from every party along the pharmaceutical supply chain. They increase their margins, while end patients pay higher drug costs because of how complex and inefficient the process is.

In the long-term, Amazon’s skillset and scale could give it the power to disrupt and simplify this supply chain — first in the form of pharmacies themselves, and later, by targeting wholesalers and PBMs.

For more on this topic, check out our research brief on the pharmaceutical supply chain.

How Amazon is going after pharma

Amazon took its first major step in the pharmacy space when it acquired the online pharmacy PillPack for around $750M in 2018.

PillPack delivers users’ medications directly to their homes. Notably, the company sends pills in pre-sorted pouches to be taken at specific times of the day. In addition to sending medications, PillPack includes info sheets that list when to take each medicine, when the current batch of prescriptions will run out, when to expect the next shipment, and more.

The PillPack user experience is designed to be clean, simple, and

more intuitive than traditional pharmacies. Image source: PillPack

PillPack’s reach is limited by its distribution licenses. Companies like PillPack that want to deliver medication nationally need to acquire a license from each state for every drug shipping warehouse. Today, it can take up to several weeks for your first PillPack order to arrive because there are only a handful of distribution warehouses, each with its own shipping limitations.

But since Amazon acquired PillPack, the company has accelerated its accumulation of distribution licenses. PillPack was granted nine new pharmacy licenses in early 2019, with at least 3 other applications pending.

Down the road, Amazon may further leverage its tech to expand its healthcare presence. For example, Amazon’s voice assistant Alexa could be used to remind patients to take medications and monitor adherence. The company recently filed a patent where Alexa can detect coughs and sniffles, then recommend cough medications or a restaurant to order soup from. And the Alexa app platform already carries lightweight healthcare apps from institutions like Mayo Clinic and Libertana to answer simple health questions, send alerts in emergencies, and help communicate with caregivers.

In the future, these capabilities could lead to Amazon getting into the diagnosis, drug recommendation, and even the prescription side of pharmaceuticals — though that future is likely some way off.

As Amazon continues to put its money and influence to work acquiring distribution licenses and potentially acquiring another mail-order pharmacy or two, it’s laying the foundation for an Amazon-branded, fast, prescription drug delivery system.

Who’s at risk?

Traditional brick-and-mortar pharmacies

Today, Amazon’s efforts in the pharmaceutical space mainly point to an attempt to disrupt the last-mile end of the pharmacy supply chain: retail pharmacies like CVS and Rite Aid.

The current process of picking up a subscription is time-consuming and inefficient, and the price that patient pay for their medicine varies based on factors like geography, insurance, and more.

Retail pharmacies’ main defense against disruption is the fact that they remain the fastest way to get a new prescription filled for most Americans.

But now, with its vast network of fulfillment centers and its PillPack acquisition, Amazon is working on a solution to this problem that could mean free 1-2 day shipping or even same-day shipping of medicines to anywhere in the US. Amazon also has footholds in the brick-and-mortar world it could leverage, through Whole Foods and its forthcoming grocery chain.

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)

In the longer-term future, Amazon could use these capabilities to take aim at one of the most lucrative — and disliked — parts of the healthcare supply chain: PBMs.

Three PBMs make up around 80% of the market in the US — CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRX.

These top three PBMs brought in $10B in profit in 2015, including from the rebates they negotiate with drug manufacturers, creating the perception that they sometimes choose to buy more expensive drugs with a higher rebate value rather than lower priced drugs with a lower rebate value — a perverse incentive for healthcare costs in the long-term.

The stated goals of Haven, Amazon’s health venture with Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan, are a direct rebuttal to PBMs claim that they save consumers money and are necessary middle men in the supply chain.

Excerpt from Jamie Dimon’s shareholder letter discussing the formation of Haven. Image source: JPMorgan

Amazon does not rely on pharmaceuticals to drive its profits, so it has the freedom to explore what could be, at first, a virtually non-profit approach to pharmacy benefit management — and with PillPack, it may have the growth engine required to reach PBM scale negotiating power.....MUCH, MUCH MORE

In 2017, PillPack filled more than $250M in cash prescriptions, a number that could grow exponentially if Amazon used its scale to lower prices and roll the service out nationwide, and potentially even incorporate it into Prime benefits.

With a large user base of consumers ordering drugs through Amazon, the company may be well-positioned to negotiate bulk discounts from drug distributors. This is already the operating model of companies like GoodRx and BlinkHealth. Amazon, however, would be able to leverage the largest member population in the United States to do it.

With lower costs in place, and a more transparent supply chain, Amazon could become an attractive alternative drug supply partner for employers who are unhappy with the rebate-driven PBM model that contributes to high drug costs for their employees.

And Amazon wouldn’t necessarily have to draw any profit from the project to make it worthwhile — as a value-adding service which helps keep people within Amazon’s ecosystem could draw customers to other money-making aspects of its business.

For more on this topic, check out our brief, Amazon In Healthcare: The E-Commerce Giant’s Strategy For A $3 Trillion Market.

2. Small business lending: A direct, data-driven source of financing

Amazon took its first steps into commercial loans back in 2011, when the company began offering small-business loans to merchants participating in its Amazon Marketplace via its new Amazon Lending arm. At that time, conditions were well-suited for Amazon’s entry into the commercial lending sector: the global financial crisis of 2008 had shaken confidence in even the largest commercial banks, initiated a credit crunch, and left millions of small businesses struggling to secure the capital they needed to survive....

Coming up, "The 1022 Thought Leaders You Absolutely Must Follow in 2019."