So after Barrick bought Homestake, I procured an Indiana Jones hat and ventured out to South Dakota to visit HM H.Q. in Lead (long 'e'), get to know the librarians at the Deadwood Public Library and tramp around the Black Hills. I was probably the last person to look at HM's records from the 1930's, I was there as the archivists were boxing the stuff up.

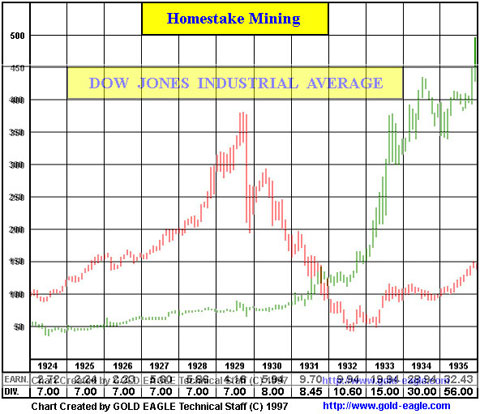

The short version of the stock action—and the dividends, look at that bottom panel in the chart, $56 in 1935, basically what the stock sold for a decade earlier, is:

There were three contributors to the move in the share price.

1) A high-grading mining strategy proposed by a young engineer, Don McLaughlin in the late '20's began bearing fruit in the form of higher recoveries. Mr. McLaughlin went on to the presidency of the company.

2) A flight to safety after the October 1929 stock market crash.

3) The Gold Reserve Act of January 30, 1934 raised the price of gold 69%, from $20.67 to $35.00 (conversely devaluing the dollar by 41%).

3a) Homestake was thus paying salaries and other expenses in devalued dollars.

This combination of more gold produced, higher price per ounce and lowered expenses (in real terms) was what moved the stock, not some inherent magic in gold.

(that's me quoting myself)

Which left me a lot of time to think about the hundreds of mines in the neighborhood, the lack of secure storage facilities, the dangerous nature of working in an area of steep gradients, heavy drinking and gunplay.

(see Wild Bill Hickock in Deadwood's Saloon #10, August 2, 1876.)

and I realized "Holy crap, there must be a lot of gold buried here by miners who went to town and never came back or fell down a shaft or just forgot where they buried it."

Apparently this was also true in the earlier California Gold Rush (and for that matter every other rush.)

From the San Francisco Chronicle, June 9, 2019:

Granville P. Swift was known for many things, but he was not known for his memory.

The Kentuckian had come to California as a 19-year-old, nine years before the Gold Rush would change the state forever. Young Swift, whose great-uncle was the legendary explorer Daniel Boone, hoped he would make his fortune in fur trapping — but he soon made his name as an insurrectionist. In 1846, Swift was one of 33 Americans who captured Sonoma during the Bear Flag Revolt. He stayed on in Sonoma for another year, commanding a company and earning the rank of captain, before the lure of wealth called to him again.

Upon the announcement of gold being discovered at Sutter's Fort, Swift set off for Bidwell's Bar with a small party. He struck it rich almost immediately.

"Swift was one of the best miners I ever knew," a fellow prospector said. "It seems as if he could almost smell the gold. He made an immense amount of gold. When these three men had worked all winter and fall, I believe they must have made $100,000 apiece and maybe more."

According to an 1875 story in the Sonoma Democrat, Swift left Bidwell's Bar with over half a million dollars in gold. He brought it to San Francisco and had it minted into octagonal slugs, $50 each, with a special mark designating them as Swift's.

Loaded down with gold — and without a banking system to receive it — Swift decided to start burying his haul around the Bay Area, primarily in the Sonoma area. The only problem was, he was very bad at remembering where he'd hidden it all. Although Swift died in 1875, the secret died long before then, forgotten by the scatter-brained settler.

Over time, some of the gold was found. In 1903, a worker on a ranch in Sonoma County dug up $7,000 in Swift's $50 slugs. A year later, $30,000 in gold was pulled from a chimney hiding place on Swift's old ranch near present-day Sears Point.

"While repairing a chimney on the second floor of the place, workmen came across a secret receptacle containing $26,000 in gold coin," the Healdsburg Enterprise reported. "In other places more money was found, the total sum aggregating more than $30,000."

The biggest discovery came in 1914.....MORE