Overcapacity reigns as companies splurge on the largest ships, consolidation rages, no one wants to back off.

In August 2016, Hanjin Shipping Co., at the time the world’s seventh largest container carrier, sought bankruptcy protection. It was the largest bankruptcy in shipping industry history. On February 2, 2017, the Seoul Bankruptcy Court declared that Hanjin Shipping would be liquidated, as restructuring its debts would be “prohibitively expensive.” But just how big was this debt load?

Hanjin Shipping had originally admitted to the equivalent of $5 billion in debts. Once the bankruptcy court got to work, there were nearly weekly announcements that more debt had been found, tucked away in nooks and crannies of the once glistening edifice. In the end, it was determined that Hanjin, when it entered receivership, actually had $10.5 billion in debts.

Hanjin had been tripped up by, among other factors, a problem that plagues the container shipping industry: overcapacity. And despite Hanjin’s liquidation, that overcapacity is getting a whole lot worse.

As of June 2018, all of the top 13 container carriers bar one had added capacity compared to a year earlier. The lone contrarian was Hyundai Merchant Marine (HMM), which is presently exiting the Transatlantic market altogether and as such is eliminating capacity. But the other 12 big container carriers more than made up for it. Here are some standouts:

Zimm Integrated Shipping Services (Israel) increased its capacity by 24.5%.

Orient Overseas Container Line (Hong Kong) added 18.4%.

CMA-CGM (France) added 16.3%. It also ordered from two state-owned Chinese shipyards nine 22,000-TEU (Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit) container carriers that will be the world’s largest when deliveries start next year. Here is a current record holder at 18,000-TEU. Note the tiny 40-foot containers stacked on top (image via CMA-CGM):...

COSCO, a state-owned product of China’s “command economy,” added 12.4%.

Maersk Line, the largest carrier by capacity, ahead of COSCO, added 10.8% in capacity.

ONE (Ocean Network Express), a brand-new company formed from the container divisions of Japan’s top three shipping companies (Mitsui-O.S.K., Nippon Yusen Kaisha and K-Line) added 7.9%, despite many promises to the contrary.

Including HMM, the average capacity increase for these 13 already huge shipping companies was 8.5%. Including all companies, big and small, container carrying capacity worldwide increased by a 9.3% year on year.

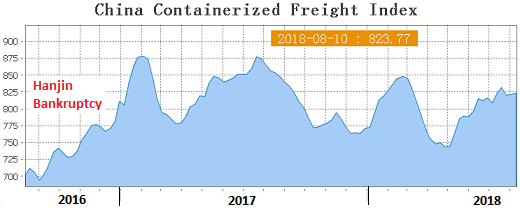

As a result, despite surging transportation inflation worldwide, the China Containerized Freight Index (CCFI), which tracks contractual and spot-market rates for shipping containers from major ports in China to 14 regions around the world, at 821 on Friday, has not fully recovered from its brutal collapse that bottomed out at 636 in April 2016. Before the collapse, it had ranged consistently above 1,000 and periodically above 1,100:

Note that just like the Baltic Dry Index, the CCFI is not a measure of trade volume, but a measure of how expensive (or cheap) it is to ship goods by sea around the world.

Only part of the collapse of the containerized freight rates in 2015 and 2016 was due to overcapacity. Another major factor was the plunge of the price of oil, and therefore of bunker, the fuel for these giant container ships.

With the CCFI well below 1,000 since 2015, while bunker prices have been rising since 2016 along with the costs of emission compliance, profits are being eroded, and momentous changes are sweeping through the industry.

Above mentioned ONE can be considered one of the poster children for this “brave new world”: it started operations on April 1, 2018 (the beginning of the fiscal year in Japan), and during its first quarter of existence has already managed to lose $120 million.

Japanese shipping companies have a time-honored tradition of ignoring losses until they become too large to be ignored, and then there’s always a big scandal followed by an emergency bailout, merger or takeover. So a measly $120 million in losses in a single quarter is of no concern to them.

AP Moller-Maersk, the parent company of Maersk Line, bought Hamburg Süd from Dr Oetker KG of Germany for €4.3 billion. In 2013 Hamburg Süd had attempted a merger with Germany’s other shipping giant, Hapag-Lloyd, but Dr Oetker KG pulled out when a satisfactory financial package could not be agreed upon....MUCH MORE

Hapag-Lloyd then merged with perpetually troubled Gulf carrier United Arab Shipping Company (UASC), resulting in a curious ownership situation. Due to previous mergers and share swaps, the largest shareholder of the “new” Hapag-Lloyd is Chile’s Grupo Luksic (20.7%), followed by three that each own 14%: Kuehne + Nagel AG (Germany, run through a shell company in Switzerland); the City of Hamburg; and Qatar’s national wealth fund, QIA. Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund owns 10%. The rest is free float....

Our last comment on the German carrier, July 9:

Hapag-Lloyd had gone through so many mergers and divestitures that I'm not even sure what they own any more although they are still the number five or six container shipper and through 'The Alliance' with Japan's ONE and China's Yang Ming can move a box pretty much anywhere in the world.And previously on Hanjin:

But that's something CMA CGM can already do, on their own or through The Ocean Alliance. so there must be some other reason for the approach, maybe efficiencies that could be wrung out of a combination.

Shipping: What the Heck Happened to Hanjin’s Ships and the Collapsed Freight Rates?

Shipping: Hanjin Re/Insurance Loss Could be $2 Billion Says Credit Suisse

Shipping: "Welcome to the Hanjin California"

"Hanjin Shipping Rebounds As Creditors Talk Of Funding Support Again"

Shipping: AP Moller-Maersk Break-up, Hanjin Breakdown

Shipping: "Following Hanjin’s Collapse, Heavily Indebted Yang Ming at Risk of Financial Trouble"