From Evergreen | Gavekal, August 10:

“While the Trump administration may crow endlessly about how swell the economy performed last quarter, that 4.1% GDP print will quickly become a wistful memory.”

-BERNARD BAUMOHL, Economist at the Economic Outlook Group

Introduction

Towards the tail-end of July, the Commerce Department reported that Gross Domestic Product (also known as GDP), or the total value of goods and services produced in the US, increased at an annual pace of 4.1% in this year’s second quarter. As expected, President Trump took a victory lap around these numbers, which were the highest GDP growth results since 2014. (However, lost in the fanfare was the fact that the first quarter GDP number was revised down from 2.9% to 2.3%.)

In an equally anticipated move, the President went on to predict that this is just the start of a long-term trend, and that these numbers are “very, very sustainable” and are “going to go a lot higher.” With all due respect to the Trumpeter-in-Chief, the Evergreen Gavekal team is not nearly as confident. In fact, we would argue that there is a glaring black hole in his economic outlook.

Particularly, we believe that three unstainable factors led to thisTHE RECESSION OF 2019

inflatedhigher-than-expected GDP number: tax cuts, a surge in government spending, and a rush to ship exports out of the country as the result of the trade war. We believe all three factors are based on high-risk policies that will eventually turn from a catalyst to a drag on the economy in the medium- to long-term—perhaps right around, if not before, President Trump seeks re-election in 2020.

This week’s Gavekal EVA comes from one of our most admired partners, Charles Gave. Charles also sees danger brewing on the economic horizon, both in the US and globally. In fact, he even goes so far as to postulate the exact year this brewing will turn into a full-fledge storm: 2019. In this week’s EVA, Charles explains his reasoning for making this bold, timestamped prediction. His forecast is based on several macro-economic factors that are already letting-on to a slowdown in the mostly elusive synchronized global expansion.

However, Evergreen itself is still holding off on issuing a call for the next recession, one we haven’t made since 2007. We admit, though, that the expansion clock is nearing midnight, which shouldn’t come as a surprise since this party has been going on for almost nine years. Keep dancing at your own risk!

By Charles Gave

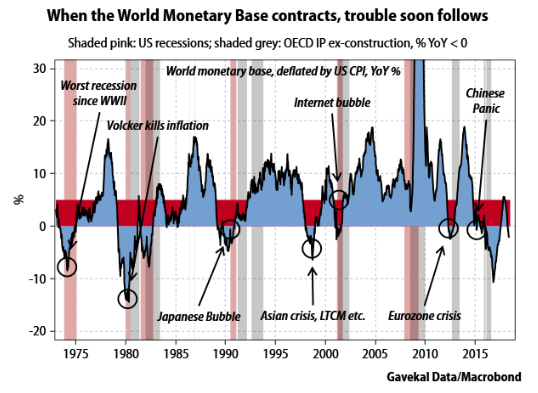

Over the last three months, I have become increasingly concerned that a recession will hit the world economy in 2019. In this paper, I shall explain why. My reasoning is simple and is based on the behavior of an indicator I have long followed, which I call the World Monetary Base, or WMB. Every time in the past that this monetary aggregate has shown a year-on-year decline in real terms, a recession has followed, often accompanied by a flock of “black swans.” And, since the end of March, the WMB has again been in negative territory in year-on-year terms. As a result, and as I shall explain, there is a significant risk of a recession next year.

The World Monetary Base (WMB)

Before I launch into a detailed examination of my reasoning, I should perhaps recap what the WMB is and why it is so important. It starts with the US Federal Reserve, which, because it controls the dominant reserve currency, acts as de facto central bank to the world. By purchasing government bonds from domestic banks, so flooding them with reserves, the Fed can engineer an increase in the US monetary base.

The Fed also provides “reserves” to other central banks. Typically, this happens when the US dollar is overvalued and/or when the US economy grows faster than the rest of the world. This combination leads to a deterioration in the US current account deficit, which means that the US starts to pump more money abroad. These excess dollars appear first in the hands of foreign private sector companies. But if they earn more than they need for working capital, they sell the excess to their local central banks in exchange for local currency.

As a result, local monetary bases rise, and the surplus US dollars get parked in central bank foreign reserves, where they show up as a line item of the Fed’s balance sheet called “assets held at the Federal Reserve Bank for the account of foreign central banks”. Increases in this item must have as their counterpart increases in the monetary bases of non-US economies (unless foreign central banks sterilize their purchases of US dollars).

So, if I take the US monetary base, and add to it the reserves deposited by foreign central banks at the Fed, I get my figure for the World Monetary Base. From this aggregate, I can get a rough idea of the pace of base money creation around the world, either through direct intervention by the Fed in the US banking system, or indirectly through US dollar accumulation by foreign central banks. When the WMB is growing, I can be relatively confident about the future nominal growth of the global economy. And when it’s contracting, it makes very good sense to worry about a recession.

As the chart above shows, it is contracting now. So, based on the experience of the past 45 years, it seems likely that the world is entering its seventh international dollar liquidity crisis since 1973.

So, as the chart above suggests, there are reasons to be alarmed. But this chart merely offers an observation, not an explanation. For the prospect of a recession in 2019 to be taken seriously, I will have to outline the sequence of events which will result in recession.

- Already the usual suspects—Argentina, Brazil, Turkey, South Africa—are having a tough time. And the times are likely to get even tougher for those countries which have external debts in US dollars coupled with a current account deficit.

- Already, the US stock market is outperforming all other major stock markets (most of which are actually going down)—a sure sign that the world is starting to suffer from a shortage of US dollars.

- Already the spreads between the US bond market and a number of government bond markets outside the US have started to widen. This is a sign that countries outside the US have started to raise interest rates in an attempt to stabilize their exchange rates. Unfortunately, the attempt is destined to fail, if, as I believe, the problem is not an overabundance of local currencies but a shortage of US dollars.

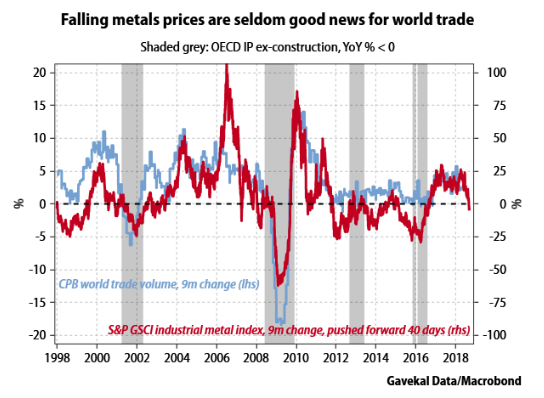

The first effect to watch out for is a contraction in international trade as a consequence of the US dollar shortage. Every time in the past that there has been a contraction in the WMB, six or so months later there has been a steep decline in the volume of world trade (at least since 1994—I only have the data back that far). These declines have almost always led to a recession, either in the OECD, or outside the OECD, as in the case of the Asian crisis. I see no reason why the same should not happen again this time around, especially as I am starting to detect a range of other signs that typically accompany the march towards a recession.

For example, if a recession is coming, it is natural to expect commodities prices to roll over. And as the chart below shows, that is what is happening.

When the volume of trade goes down, together with the prices of commodities, commodity-producers (essentially the emerging markets outside Asia) usually see their stock markets tank. And ex-Asian emerging markets have certainly taken a beating recently....MUCH MOREHT: ZeroHedge

Because we're pretty sure Mr. Gave is early, we'll keep on dancing.