From Reaction Magazine:

This question – could Rome have had an industrial revolution? – is prompted by

Kingdom of the Wicked, a

new book by Helen Dale. Dale forces us to consider Jesus as a religious

extremist in a Roman world not unlike our own. The novel throws new

light on our own attitudes to terrorism, globalization, torture, and the

clash of cultures. It is highly recommended.

Indirectly, however,

Dale also addresses the possibility of sustained economic growth in the

ancient world. The novel is set in a 1st century Roman empire during the

governorship of Pontus Pilate and the reign of Tiberius. But in this

alternative history, the Mediterranean world has experienced a series of

technical innovations following the survival of Archimedes at the siege

of Syracuse, which have led to rapid economic growth. As Dale explains

in the book’s excellent afterword (published separately

here),

if Rome had experienced an industrial revolution, it would likely have

differed from the actual one; and she briefly plots a path to Roman

industrialization. All of this is highly stimulating and has prompted me

to speculate further about whether Rome could have experienced modern

economic growth and if Dale’s proposed path towards a Roman Industrial

Revolution is plausible.

Roman Economic Prosperity

For decades, historians

were deeply skeptical of the potential of the ancient world to generate

sustained economic growth. Influenced by Moses Finlay and Karl Polanyi,

historians saw the ancient and modern worlds as separated by a cultural

and economic chasm. Prior to the Industrial Revolution-era leaping of

this chasm, individuals supposedly lacked “economic rationality,” did

not seek opportunities to maximize profit, and were disinclined to use

new technology for economic purposes.

This view is no longer credible. In his recent book,

The Fate of Rome,

Kyle Harper depicts

a Roman economy which supported both population growth and rising per

capita incomes. It was an economy in which inequality was high— the rich

were super rich — but even the middling classes or urban poor had

access to a wide range of premodern “consumer goods”. Moreover,

according to Harper, this was based on market-orientated Smithian

growth:

“Peace,

law, and transportation infrastructure fostered the capillary

penetration of markets everywhere. The clearing of piracy from the

Mediterranean in the late Republic may have been the single most

critical precondition for the burst of commercial expansion that the

Romans witnessed; risk of harm has often been the costliest impediment

to seaborne exchange. The umbrella of Roman law further reduced

transaction costs. The dependable enforcement of property rights and a

shared currency regime encouraged entrepreneurs and merchants . . .

Roman banks and networks of commercial credit offered levels of

financial intermediation not attained again until the most progressive

corners of the seventeenth-eighteenth century global economy. Credit is

the lubricant of commerce, and in the Roman empire the gears of trade

whirred” (Harper, 2017, p 37).

This assessment

is bold but consistent with the recent findings of archaeologists who

continue to uncover evidence of dense trading networks and widespread

ownership of industrially produced consumption goods across the empire.

Willem Jongman’s chapter in the recent

Cambridge History of Capitalism summarizes many of these new findings:

“crucial

performance indicators show dramatic aggregate and per capita increases

in production and consumption from the 3rd century BCE, or sometimes a

bit later, until the Roman economy reached a spectacular peak during the

1st century BCE and the 1st century CE, lasting until perhaps the

middle of the 2nd century CE” (Jongman, 2015, 81).

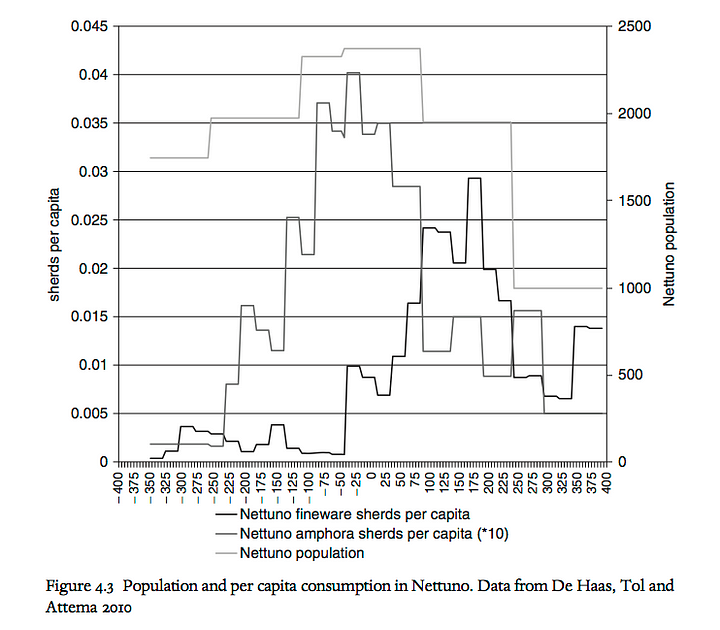

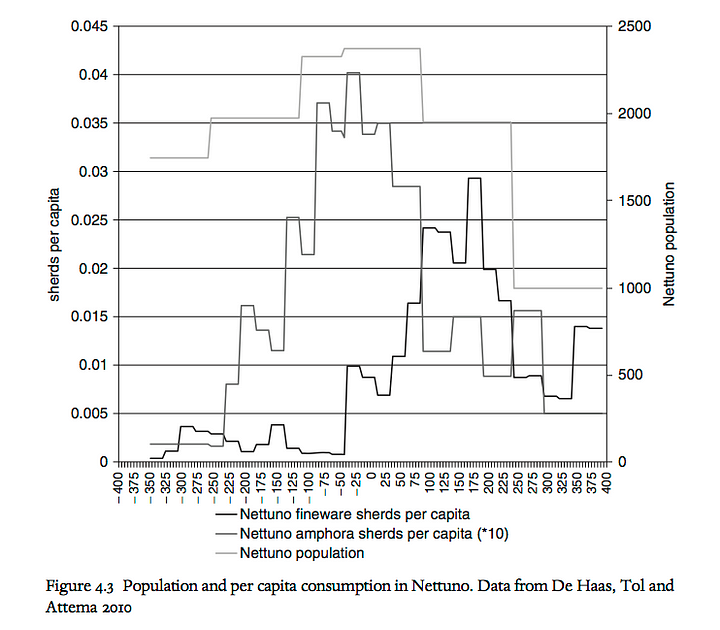

Jongman’s

chapter provides evidence of intensified coal production, pollution,

building construction, and animal consumption. I’ve reproduced one of

his figures. It depicts the rapid increase in pottery shards from

Netturo (approximately 50 km south of Rome) in these centuries.

But at

even the Roman empire at its peak in the reign of Marcus Aurelius does

not appear to have been on the verge of modern economic growth. Rome

lacked some of the crucial characteristics of Britain on the eve of the

Industrial Revolution. There was no culture of invention and discovery,

no large population of skilled tinkerers or machine builders, and no

evidence of labor scarcity that might have driven the invention of

labor-saving inventions.

The Roman Counter-Factual

Before concluding that a

Roman Industrial Revolution was impossible, however, perhaps some

caution is required. In many respects the British Industrial Revolution

was overdetermined. Nick Crafts made this point eloquently almost 40

years ago in his

comparison of Britain and France:

“there

are no “covering laws” which explain England’s primacy; the best we can

do is to formulate explanatory generalizations with an error term.

Given that the “event” is unique, the tools of statistical inference are

inadequate to explain the timing of decisive innovations . . .

Furthermore, if the Industrial Revolution is thought of as the result of

a stochastic process, the question, “Why was England first?” is

misconceived: the observed result need not imply the superiority of

antecedent conditions in England” (Crafts, 1978).

Craft’s point

is that the timing of Industrial Revolution was partly random and, in

the absence of repeated experiments, we will never have precise causal

estimates of the impact of any single factor that distinguished 18th

century England, from France, Qing China, or indeed ancient Rome. All

that we can say is that the balance of probabilities was such so as to

make an economic breakthrough much more likely in 18th century Europe

than in China or the ancient world....

MUCH MORE