We don't always agree with him but he is a heavyweight.

A look at his c.v. turns up at least three Nobel Laureates among his co-authors and he hangs his hat at Yale's Cowles Foundation which has employed ten or twelve other Nobelists.

Professor Gordon scares me. If he is right, the 250 year period 1750-2000 was a one-off, economic growth is not the natural state of human endeavor and entropy rules the universe.

From the New York Review of Books:

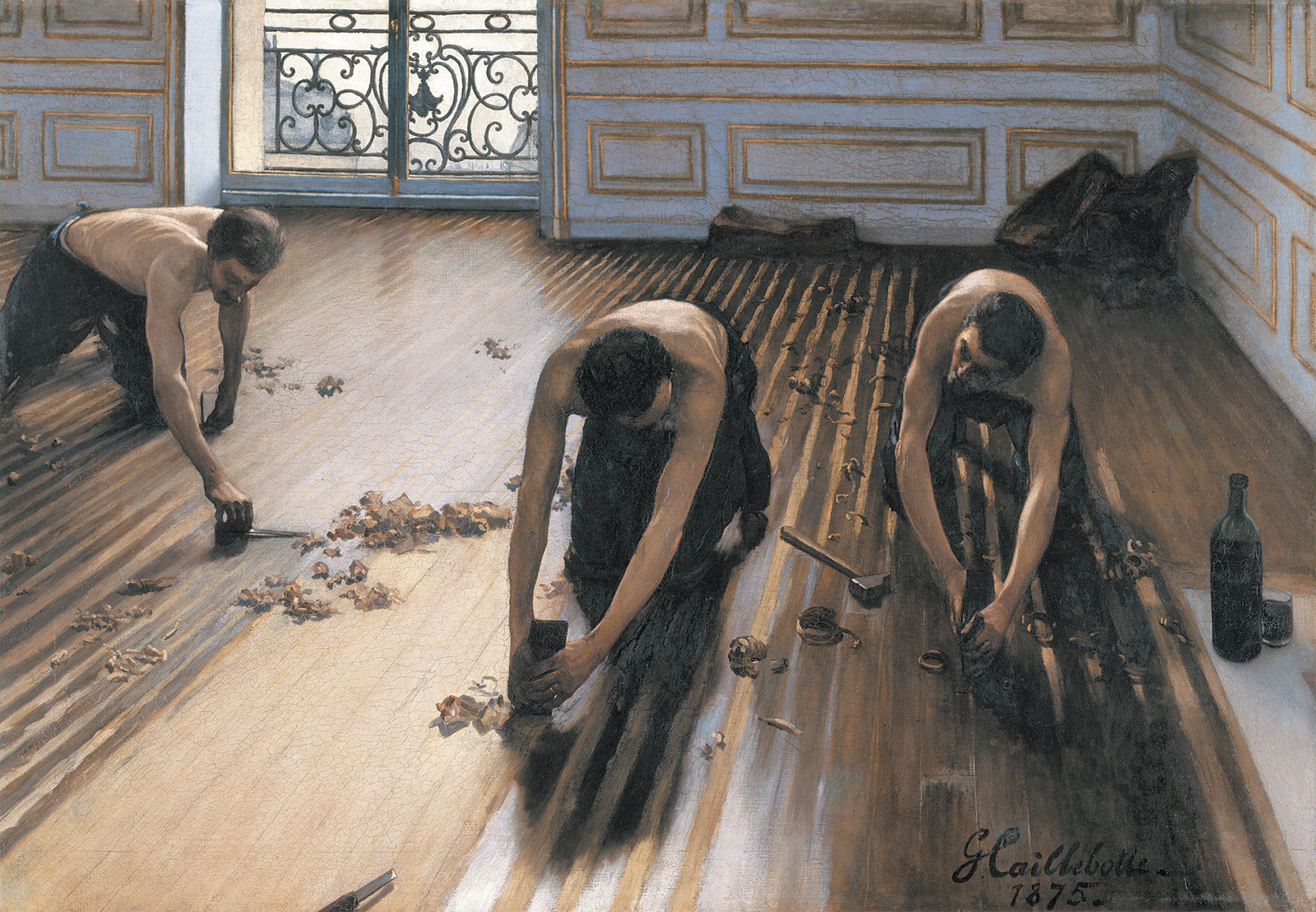

Gustave Caillebotte: The Floor Planers, 1875

Robert Gordon has written a magnificent book on the economic history of the United States over the last one and a half centuries. His study focuses on what he calls the “special century” from 1870 to 1970—in which living standards increased more rapidly than at any time before or after. The book is without peer in providing a statistical analysis of the uneven pace of growth and technological change, in describing the technologies that led to the remarkable progress during the special century, and in concluding with a provocative hypothesis that the future is unlikely to bring anything approaching the economic gains of the earlier period.HT: FT Alphaville's Further Reading post, August 1

The message of Rise and Fall is this. For most of human history, economic progress moved at a crawl. According to the economic historian Bradford DeLong, from the first rock tools used by humanoids three million years ago, to the earliest cities ten thousand years ago, through the Middle Ages, to the beginning of the Industrial Revolution around 1800, living standards doubled (with a growth of 0.00002 percent per year). Another doubling took place over the subsequent period to 1870. Then, according to standard calculations, the world economy took off.

Gordon focuses on growth in the United States. Living standards, as measured by GDP per capita or real wages, accelerated after 1870. The growth rate looks like an inverted U. Productivity growth rose from the late nineteenth century and peaked in the 1950s, but has slowed to a crawl since 1970. In designating 1870–1970 as the special century, Gordon emphasizes that the period since 1970 has been less special. He argues that the pace of innovation has slowed since 1970 (a point that will surprise many people), and furthermore that the gains from technological improvement have been shared less broadly (a point that is widely appreciated and true).

A central aspect of Gordon’s thesis is that the conventional measures of economic growth omit some of the largest gains in living standards and therefore underestimate economic progress. A point that is little appreciated is that the standard measures of economic progress do not include gains in health and life expectancy. Nor do they include the impact of revolutionary technological improvements such as the introduction of electricity or telephones or automobiles. Most of the book is devoted to describing many of history’s crucial technological revolutions, which in Gordon’s view took place in the special century. Moreover, he argues that the innovations of today are much narrower and contribute much less to improvements in living standards than did the innovations of the special century.

Rise and Fall represents the results of a lifetime of research by one of America’s leading macroeconomists. Gordon absorbed the current thinking on economic growth as a graduate student at MIT from 1964 to 1967 (where we were classmates), studying the cutting-edge theories and empirical work of such brilliant economists as Paul Samuelson, Robert Solow, Dale Jorgenson, and Zvi Griliches. He soon settled in at Northwestern University, where his research increasingly focused on long-term growth trends and problems of measuring real income and output.Gordon’s book is both physically and intellectually weighty. While handsomely produced, at nearly eight hundred pages it weighs as much as a small dog. I found the Kindle version more convenient. Here is a guide to the principal points.

The first chapter summarizes the major arguments succinctly and should be studied carefully. Here is the basic thesis:

The century of revolution in the United States after the Civil War was economic, not political, freeing households from an unremitting daily grind of painful manual labor, household drudgery, darkness, isolation, and early death. Only one hundred years later, daily life had changed beyond recognition. Manual outdoor jobs were replaced by work in air-conditioned environments, housework was increasingly performed by electric appliances, darkness was replaced by light, and isolation was replaced not just by travel, but also by color television images bringing the world into the living room…. The economic revolution of 1870 to 1970 was unique in human history, unrepeatable because so many of its achievements could happen only once.The series of “only once” economic revolutions behind this short summary makes up the next fourteen chapters of the book. Most of the innovations are familiar, but Gordon tells their histories vividly. More important, in many cases, he explains quantitatively the way these economic revolutions boosted the living standards of the statistically average American. Among the most illuminating chapters are those on housing, transportation, health, and computers.

The last two chapters are about the fall in Rise and Fall. This book differs from the Spenglerian “decline of the West” genre in an important respect. As the mathematicians might say, Gordon moves up a derivative. In other words, he is not predicting that living standards in the US will decline; rather he views it as likely that the growth rate of living standards will decline from its very rapid pace in the special century.

Gordon sees two sources for his pessimistic outlook. The first is that the long list of “only once” social and economic changes cannot be repeated. A second source is what he calls “headwinds.” These are structural changes in the economy that reduce actual output below the country’s technological potential and provide another reason for slow growth in living standards in the decades ahead....MUCH MORE

For more on Gordon's thinking:

Why Professor Gordon's New Book On Growth and Innovation Matters

Heads Up: "Robert Gordon’s magnum opus, The Rise and Fall of American Growth: the US Standard of Living Since the Civil War (out in mid-January)"

Economists Debate: Has All the Important Stuff Already Been Invented?

"Is Growth Destined to Slow?"

The Coming Productivity Shock

Byron Wien: How to Profit From Productivity Puzzle"

For those in search of the full experience, FT Alphaville has a lot of posts, and here's a conversation at the University of Chicago I was going to link to but decided against at the time. From the Booth School of Business' Capital Ideas magazine:

Transcript: Can innovation save the US economy?