There’s no yield, and Citi isn’t going to take it anymore

Citi’s Matt King has some harsh words for central bankers ahead of this week’s gathering in Jackson Hole, Wyoming: he says they’ve broken the market.

King echoes a group of fund managers who say central banks’ stimulus efforts are distorting the way global markets function. The problem is this: with negative yields on $13 trillion of safe assets, investment managers are crowding into the shrinking group of investments with yield — or into securities they may be able to sell to central banks.

This has been frustrating for those fund managers, to say the least. (This journalist remembers getting laughed at when she asked an expert how to determine the value of a Treasury security, because the Federal Reserve still owns more than $2 trillion of them.)

Instead of gauging market fundamentals in their decisions, investors are primarily concerned with the outlook for central bank policy. So they crowd into trades that could profit off of the actions of central bankers in Europe, Japan or the UK. That’s why Bill Gross and Paul Singer have both bemoaned the effect central banks have had on the global markets and the economy recently. Gross says it’s causing growth to stagnate, and Singer is warning of a sharp reversal.

King agrees. Here are some of the reasons he thinks markets are broken:

A greater share of global equity-market variance is explained by macro factors, according to the bank’s quant team. From his note: “When there’s only one factor dominating markets, it inevitably forces investors the same way round.”

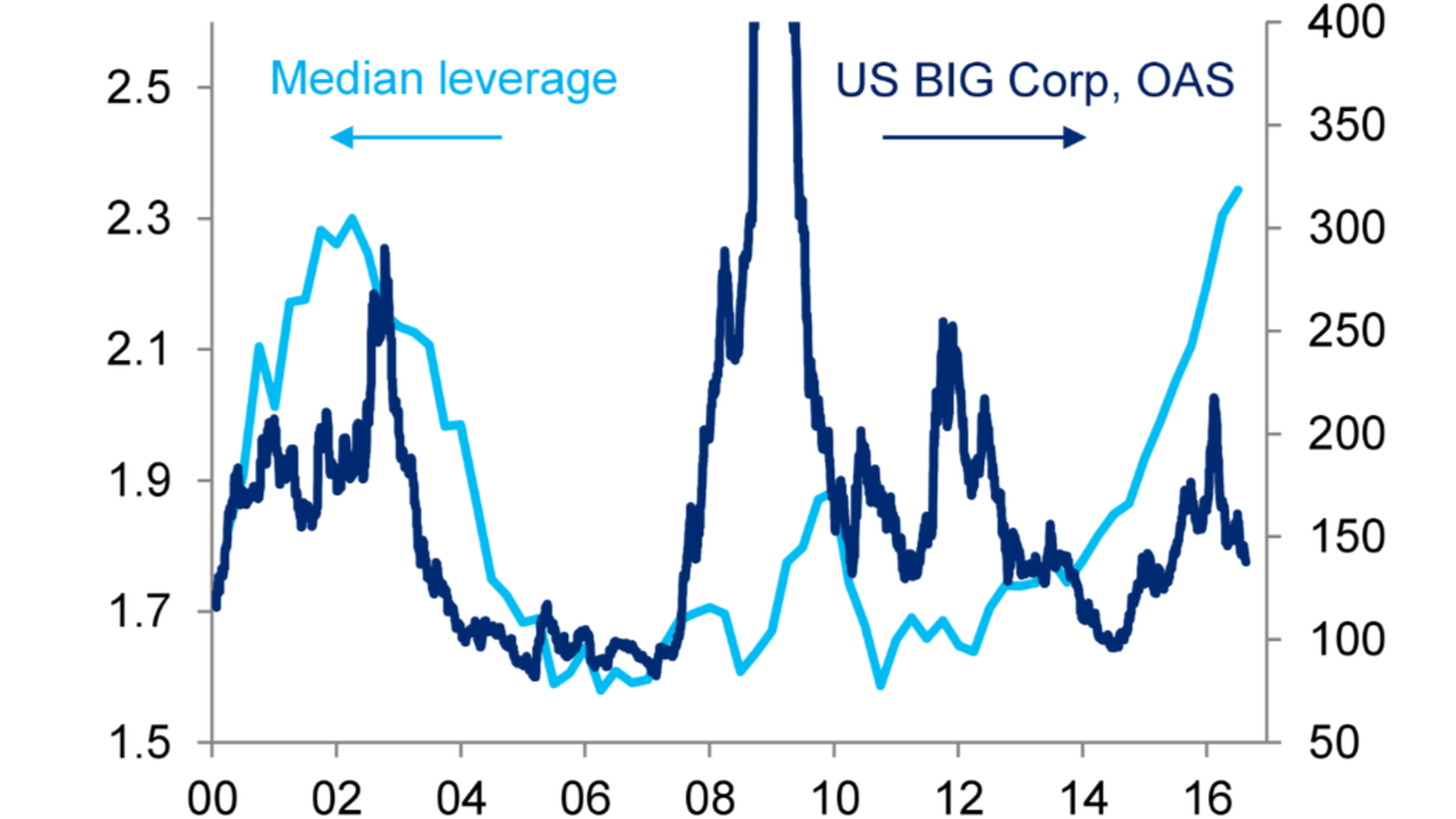

Credit spreads aren’t responding to climbing leverage and defaults. If defaults and leverage are higher, you’d expect investors to demand more yield to own a security — unless, of course, they think they’ll be able to sell it to a central bank soon:

Normal market relationships are breaking down. King says the traditional relationship between government debt and credit has broken down. Normally, if yields fall it’s a sign investors are seeking out safety, which should coincide with wider spreads. But he finds that the 10-year bund yield and European investment-grade credit spreads have tended to move in the same direction since 2014: “Either it all rallies, in a gigantic reach for yield – or it all sells off. The benefits of diversification just went completely out of the window. No wonder investors are hiding in alternatives: at least they don’t have to mark to market.” ......MORE