Or Frederick Jackson Turner meets Modern Portfolio theory.

For our non-U.S. readers, Turner was an historian who caused quite a sensation with his 1893 interpretation of the 1890 Census Bureau statement that the Frontier line, a point beyond which the population density was less than two persons per square mile, no longer existed.

Turner developed an entire cosmology around the frontier thesis encompassing rugged individualism, resource wastage, optimism and pretty much every other cliché of the era.

With the closing of the frontier it was a whole new world for Americans who had believed that, forged in adversity, they were a breed unique on the earth.

So much for that Weltanschauung.

Regarding the efficient frontier, last year I dropped a comment at MarketBeat:

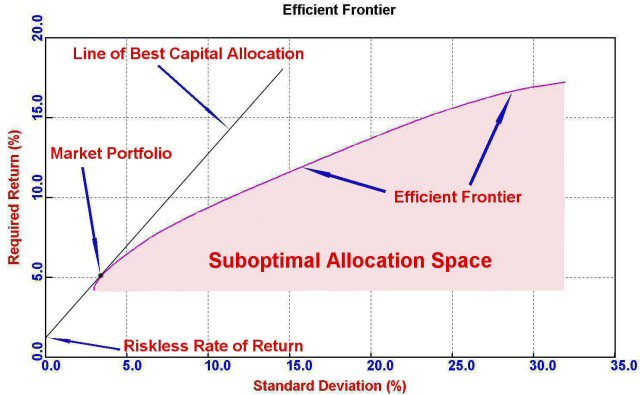

...The key issue is that a downgrade spells the death of “risk-free“. Without a veritable “risk-free” rate, it’s a brave new world in finance, where all prices suddenly become meaningless....Yeah, that pretty much nails it.

Here's Alphaville with another look at a world unmoored:

Welcome to the ‘Desert of the Real’ — a postmodern economy

Volatility guru Christopher Cole, who heads up the volatility fund Artemis Capital Management, is known for making interesting arguments when it comes to volatility and risk. Previous philosophical thoughts have questioned the concept of volatility, proposed that risk itself is changing, and that QE and other forms of government intervention are warping volatility beyond recognition.

His latest note, though, takes us to an entirely new dimension of market abstraction.

Here’s a starter sample:

Modern financial markets are a game of impossible objects. In a world where global central banks manipulate the cost of risk the mechanics of price discovery have disengaged from reality resulting in paradoxical expressions of value that should not exist according to efficient market theory. Fear and safety are now interchangeable in a speculative and high stakes game of perception. The efficient frontier is now contorted to such a degree that traditional empirical views are no longer relevant.We, for one, like where he’s going with this.

—

Likewise how certain are we that the elevated two-dimensional prices of risk assets and low spot volatility have anything to do with fundamental three-dimensional reality? In this brave new world volatility is an important dimension of risk because it can measure investor trust in the market depiction of the future economy. The problem is that the abstraction of the market has become an economic reality unto itself. You can no longer play by the old rules since those rules no longer apply. I know what you are thinking. You didn’t get your MBA to be an amateur philosopher – your job is to make cold-hard decisions about real money – not read Plato. You are out of luck. For the next decade this market is going to reward philosophers over students of business. Why? Because the modern investor must hold several contradictory ideas in his or her head at the same time and none of them really make any sense according to business school case studies. Welcome to the impossible market where…

His point seems to be that it’s not just a question of the old rules changing. More that we may be standing on the edge of a paradigm shift so unexpected that nobody has yet been able to imagine it. A shift, we dare say, that could take conventional business and investment practice and spin it on its head entirely.

For now that means volatility is both cheap and expensive, according to Cole.

In many respects it’s a quantum investing universe.

This makes sense to us since it suggests that value itself can only really be determined by an independent observer, subjectively. Until it’s observed, it can be both valued and not valued simultaneously. Or perhaps, weirder still, there is no universal value system at all?

If that’s not mind-bending enough, here’s some more reflective thought from Cole...MUCH MORE

When writing algorithms requiring a risk-free rate e.g. an old-fashioned Black-Scholes model or a Sharpe ratio, is it possible to substitute something for short dated T-bills?

I’m thinking of using Δy of Apple common.