Mr. Buffet originally said this in relation to the (formerly) monoline insurers, one line of business, insuring muni bonds but it is very important on an individual level as well.

More after the jump.

If you are going to live in the United States do not be resident in one of the high liability state and do not become a creditor to those states.

From Reason Magazine, May 7, 2019:

Buffett's advice should be yet another public nudge for states to look closer at curbing their pension costs and keeping tax burdens at bay.

If you have ever wondered if public pension underfunding is relevant and plan on moving states, Warren Buffett has something to share with you: “If I were relocating into some state that had a huge unfunded pension plan I’m walking into liabilities,” he said in a recent interview with CNBC.

Defined benefit (DB) pensions for public workers have long been providing guaranteed lifetime retirement benefits, which usually have strong legal protections. Every new teacher, firefighter, or other public worker hired adds to a state’s pension liability, but it’s the unfunded portion of these liabilities that is of growing concern.

In fact, underfunding of American public pensions might be anywhere from $1.6 trillion to $5.96 trillion, depending on the methods used to discount the liability. Due mainly to historically underperforming investment returns (or overly optimistic return assumptions), insufficient pension contributions, and deviations from a host of actuarial assumptions, many state and local taxpayers are now on the hook for increasingly high pension contributions for decades to come.

The Arkansas Public Employees Retirement System (APERS), whose debt has ballooned over the past 22 years from $229 million overfunded in 1997 to $2.28 billion underfunded last year, and only 79 percent funded today, is one of the many examples of this phenomenon that can be seen nationwide.

Figure 1: Pension Solvency of APERS from 1997 to 2018

Source: Pension Integrity Project analysis of APERS valuation reports and Consolidated Annual Financial Reports (CAFRs)

Unsurprisingly, a public pension plan with an ever-growing mountain of pension debt, which itself accrues interest over time, costs much more for the taxpayer to operate than the one without. An analysis of pension debt per person illustrates this concept.

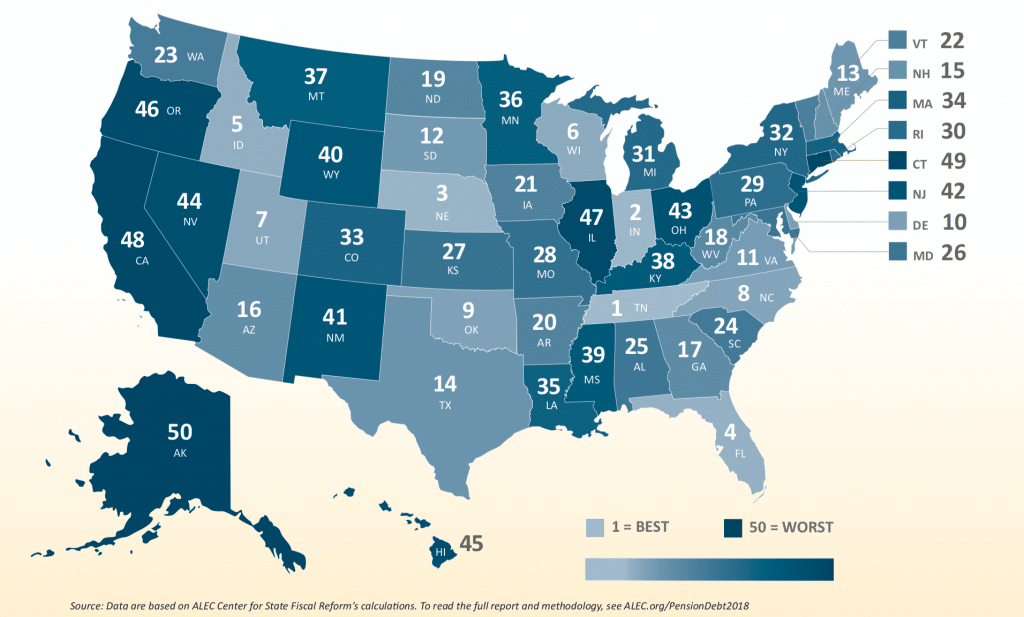

According to the American Legislative Exchange Council—which discounts pension liabilities using more conservative assumptions—the four states with the most burdensome levels of pension debt last year were Alaska, Connecticut, California, and Illinois—with each person on the hook for over $28,000 in unfunded pension liabilities in those states.

Meanwhile, Tennessee, Indiana, Nebraska, and Florida were among the least entrenched in pension shortfalls—with the pension debt price tag below $11,000 per person.

Figure 2: Unfunded Pension Liabilities Per Capita, 2018

Source: Data are based on ALEC Center for State Fiscal Reform’s calculations. To read the full report and methodology, see ALEC.org/PensionDebt2018

In his interview, Mr. Buffett elaborated on the effect this issue might have on individuals and companies looking to establish themselves in a state with underfunded pensions: “I say to myself, ‘Why do I wanna build a plant there that has to sit there for 30 or 40 years?’ Because I’ll be here for the life of the pension plan, and they will come after corporations, they’ll come after individuals…[T]hey’re gonna have to raise a lotta money.”Indeed, in 2018 the Chicago Fed released a report calling for a statewide property tax to pay off Illinois’ unfunded pension liabilities, which could be as high as $250 billion according to Moody’s Investor Services.Not only that, just last year Illinois—a state with one of the nation’s worst credit ratings—was seriously considering borrowing a whopping $107 billion via a pension obligation bond (POB)— a shaky method of kicking the pension can down the road without meaningfully alleviating pension risks for future taxpayers or reducing costs.

Chicago, which funneled as much as 27.6 percent of its 2017 budget into public pension contributions, is probably one of the starkest examples of this problem. To shore up the unfunded portion of the city’s promised benefits, former Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel initiated numerous taxes, from a large property tax hike in 2014 to a 911 communication tax. Once all of these tax increases are fully implemented, the average Chicagoan will be paying around $1,700 more in taxes each year.....

....MUCH MORE

Keep in mind that this was written before the covid-19 lockdowns destroyed any semblance of state and municipal finance rationality.

In his 2008 Chairman's Letter to the Berkshire Hathaway shareholders Mr. Buffet laid out the prime risk of insuring munis: Moral Hazard. Politicians will do anything to avoid disturbing their public employees, source of votes and more importantly campaign contributions. Here is part of a much longer 2010 post "Buffett’s ‘Dangerous Business’ Ensnares Municipal Bond Insurers (ABK; AGO; BRK-A; BRK-B; MBI)":

From the 2008 Chairman's Letter (emphasis mine):

...Tax-Exempt Bond InsuranceEarly in 2008, we activated Berkshire Hathaway Assurance Company (“BHAC”) as an insurer of the tax-exempt bonds issued by states, cities and other local entities. BHAC insures these securities for issuers both at the time their bonds are sold to the public (primary transactions) and later, when the bonds are already owned by investors (secondary transactions).

By yearend 2007, the half dozen or so companies that had been the major players in this business had all fallen into big trouble. The cause of their problems was captured long ago by Mae West: “I was Snow White, but I drifted.”

The monolines (as the bond insurers are called) initially insured only tax-exempt bonds that were low-risk. But over the years competition for this business intensified, and rates fell. Faced with the prospect of stagnating or declining earnings, the monoline managers turned to ever-riskier propositions. Some of these involved the insuring of residential mortgage obligations. When housing prices plummeted, the monoline industry quickly became a basket case.

Early in the year, Berkshire offered to assume all of the insurance issued on tax-exempts that was on the books of the three largest monolines. These companies were all in life-threatening trouble (though they said otherwise.) We would have charged a 11⁄2% rate to take over the guarantees on about $822 billion of bonds. If our offer had been accepted, we would have been required to pay any losses suffered by investors who owned these bonds – a guarantee stretching for 40 years in some cases. Ours was not a frivolous proposal: For reasons we will come to later, it involved substantial risk for Berkshire.

The monolines summarily rejected our offer, in some cases appending an insult or two. In the end, though, the turndowns proved to be very good news for us, because it became apparent that I had severely underpriced our offer.

Thereafter, we wrote about $15.6 billion of insurance in the secondary market. And here’s the punch line: About 77% of this business was on bonds that were already insured, largely by the three aforementioned monolines. In these agreements, we have to pay for defaults only if the original insurer is financially unable to do so.

We wrote this “second-to-pay” insurance for rates averaging 3.3%. That’s right; we have been paid far more for becoming the second to pay than the 1.5% we would have earlier charged to be the first to pay. In one extreme case, we actually agreed to be fourth to pay, nonetheless receiving about three times the 1% premium charged by the monoline that remains first to pay. In other words, three other monolines have to first go broke before we need to write a check.

Two of the three monolines to which we made our initial bulk offer later raised substantial capital. This, of course, directly helps us, since it makes it less likely that we will have to pay, at least in the near term, any claims on our second-to-pay insurance because these two monolines fail. In addition to our book of secondary business, we have also written $3.7 billion of primary business for a premium of $96 million. In primary business, of course, we are first to pay if the issuer gets in trouble.

We have a great many more multiples of capital behind the insurance we write than does any other monoline. Consequently, our guarantee is far more valuable than theirs. This explains why many sophisticated investors have bought second-to-pay insurance from us even though they were already insured by another monoline. BHAC has become not only the insurer of preference, but in many cases the sole insurer acceptable to bondholders.

Nevertheless, we remain very cautious about the business we write and regard it as far from a sure thing that this insurance will ultimately be profitable for us. The reason is simple, though I have never seen even a passing reference to it by any financial analyst, rating agency or monoline CEO.

The rationale behind very low premium rates for insuring tax-exempts has been that defaults have historically been few. But that record largely reflects the experience of entities that issued uninsured bonds. Insurance of tax-exempt bonds didn’t exist before 1971, and even after that most bonds remained uninsured.

A universe of tax-exempts fully covered by insurance would be certain to have a somewhat different loss experience from a group of uninsured, but otherwise similar bonds, the only question being how different. To understand why, let’s go back to 1975 when New York City was on the edge of bankruptcy. At the time its bonds – virtually all uninsured – were heavily held by the city’s wealthier residents as well as by New York banks and other institutions. These local bondholders deeply desired to solve the city’s fiscal problems. So before long, concessions and cooperation from a host of involved constituencies produced a solution. Without one, it was apparent to all that New York’s citizens and businesses would have experienced widespread and severe financial losses from their bond holdings.

Now, imagine that all of the city’s bonds had instead been insured by Berkshire. Would similar belttightening, tax increases, labor concessions, etc. have been forthcoming? Of course not. At a minimum, Berkshire would have been asked to “share” in the required sacrifices. And, considering our deep pockets, the required contribution would most certainly have been substantial.

Local governments are going to face far tougher fiscal problems in the future than they have to date. The pension liabilities I talked about in last year’s report will be a huge contributor to these woes. Many cities and states were surely horrified when they inspected the status of their funding at yearend 2008. The gap between assets and a realistic actuarial valuation of present liabilities is simply staggering.

When faced with large revenue shortfalls, communities that have all of their bonds insured will be more prone to develop “solutions” less favorable to bondholders than those communities that have uninsured bonds held by local banks and residents. Losses in the tax-exempt arena, when they come, are also likely to be highly correlated among issuers. If a few communities stiff their creditors and get away with it, the chance that others will follow in their footsteps will grow. What mayor or city council is going to choose pain to local citizens in the form of major tax increases over pain to a far-away bond insurer?

Insuring tax-exempts, therefore, has the look today of a dangerous business – one with similarities, in fact, to the insuring of natural catastrophes. In both cases, a string of loss-free years can be followed by a devastating experience that more than wipes out all earlier profits. We will try, therefore, to proceed carefully in this business, eschewing many classes of bonds that other monolines regularly embrace.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

The type of fallacy involved in projecting loss experience from a universe of non-insured bonds onto a deceptively-similar universe in which many bonds are insured pops up in other areas of finance. “Back-tested” models of many kinds are susceptible to this sort of error. Nevertheless, they are frequently touted in financial markets as guides to future action. (If merely looking up past financial data would tell you what the future holds, the Forbes 400 would consist of librarians.)

Indeed, the stupefying losses in mortgage-related securities came in large part because of flawed, history-based models used by salesmen, rating agencies and investors. These parties looked at loss experience over periods when home prices rose only moderately and speculation in houses was negligible. They then made this experience a yardstick for evaluating future losses. They blissfully ignored the fact that house prices had recently skyrocketed, loan practices had deteriorated and many buyers had opted for houses they couldn’t afford. In short, universe “past” and universe “current” had very different characteristics. But lenders, government and media largely failed to recognize this all-important fact.

Investors should be skeptical of history-based models. Constructed by a nerdy-sounding priesthood using esoteric terms such as beta, gamma, sigma and the like, these models tend to look impressive. Too often, though, investors forget to examine the assumptions behind the symbols. Our advice: Beware of geeks bearing formulas.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

A final post-script on BHAC: Who, you may wonder, runs this operation? While I help set policy, all of the heavy lifting is done by Ajit and his crew. Sure, they were already generating $24 billion of float along with hundreds of millions of underwriting profit annually. But how busy can that keep a 31-person group?

Charlie and I decided it was high time for them to start doing a full day’s work.