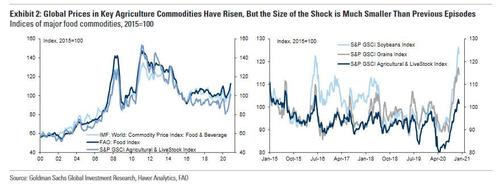

In

short, Goldman dismisses the risk of surging food inflation especially

in emerging markets, because "given the limited size of the shock to

date, and with other factors (such as spare capacity) weighing on EM

inflation, the recent rise in agricultural commodity prices

would need to extend quite a bit further for it to have a significant

and lasting effect on inflation and monetary policy across the majority

of EMs."

One wonders if Goldman was just as dismissive

during the food price surge observed in late 2010 that ultimately

culminated in the Arab Spring of early 2011. As the Guardian reminds us:

"A

decade ago this week, a young fruit seller called Mohammed Bouazizi set

himself alight outside the provincial headquarters of his home town in

Tunisia, in protest against local police officials who had seized his

cart and produce.”

It is this backdrop that

brings us a far more concerning note published this morning from

everyone's favorite permabear, SocGen's Albert Edwards, who unlike

Goldman is starting to worry about food inflation. A lot.

As Edwards explains, for much of the past decade he - and other Fed

skeptics - have railed about the distorting impact of QE on asset

prices. And aside from capital markets where the Fed's intervention has

spawned a record wealth divide leading to unprecedented political and

social polarization, perhaps the most disturbing episode of such

distortion was the abovementioned explosion of food prices that began

towards the end of 2010. According to Edwards, many economists - this website included - believe the

Fed’s QE2 was the primary cause for the 2010-11 bubble in food prices

which contributed to the social unrest and ensuing revolutions in many

Arab countries.

This is a problem because in a time when central banks are injecting a record $1.4 billion in liquidity every hour,

and when most economists’ attention is now focused on the impact of the

Fed’s QE on buoyant equity and industrial commodity prices, Albert says

that "we should also watch the unfolding surge in food prices very

closely indeed – and with trepidation."

The

reason for that is again what happened in early 2011 in Tunisia: That

event marked the start of a chain reaction of social unrest around the

Middle East and elsewhere that toppled governments and became known as

the Arab Spring, Edwards writes and adds that "although the narrative of

these revolutions had its origins in longstanding grievances and a

thirst for democracy, many economists identified rocketing global food

prices from the end of 2010 as the trigger. (T’was always so:

certainly, higher food prices contributed to both the French and Russian

revolutions, and to the 1989 unrest in China.)"

As for

whether central banks were responsible for these revolutionary dominoes,

Edwards is a bit more nuanced, writing that while they certainly

spawned much of the asset reflation observed in late 2010, "the

truth is that central banks have no control over which financial bubbles

will ultimately emerge as they spray QE into financial markets." It just so happens that food is one of them with alarming periodicity.

Case in point: bitcoin, which is soaring precisely because institutions have finally realized that central banks injecting 0.66% of GDP into capital markets every month will lift everything, even digital tokens with no intrinsic value. It will certainly lift food prices too.

They go on to show a chart of the start of the Arab Spring and rising food prices. It's a spurious correlation. We double-checked Libya and Syria at the time that bit of misdirection was making the rounds and what was being touted as the cause was actually just blather and possibly cover for the West mucking about in the region.

Didn't check food availability in Egypt or where it all began, Tunisia though. so maybe.