It's a very solid look at one of the smarter and more intellectually flexible people in fund management.

As an example, despite personally backing 'remain' on the Brexit vote to the tune of $5 mil., he was one of the few managers to make money off the 'Leave' result.

See the FT's "Hedge funds win big from Brexit bets".

Plus, the last time I looked he had just over $100 million worth of NVIDIA,what more needs to be said?

(just kidding, I'm not really that arrogant)

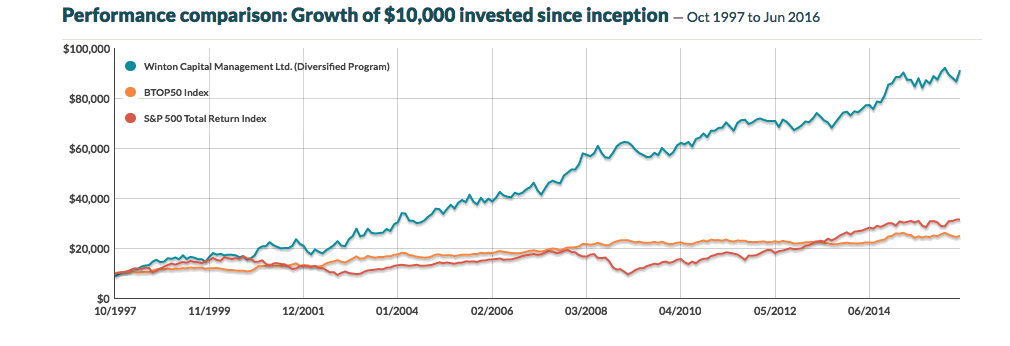

Here's Winton's performance vs. the S&P and the BarclayHedge index (BTOP50):

The founder of the $32bn hedge fund talks about physics, philanthrophy and why he believes in tax

In 1994 the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, a leading scientific journal, published an unusual paper. Entitled “Making money from mathematical models”, it was authored by a young financial trader in London. His name was David Harding, he was a Cambridge physics graduate and he used the paper to lay out what he saw as the “intellectual front line” of investment research. Harding’s idea was that finance could use science to identify and exploit inefficiencies in the markets.As the author of the piece, the FT's science writer Clive Cookson points out, the approach is similar to that of Renaissance Technologies.

He was right. Today Harding is worth about £1.3bn and, in the course of putting those initial ideas profitably into action, has become one of Europe’s leading financial entrepreneurs. His privately owned investment company Winton Capital (for which he reluctantly accepts the “hedge fund” label) manages $32bn of assets. When I take a copy of his Royal Society publication out of my briefcase, his face breaks into a slightly mischievous smile. “I’m terribly impressed that you have a copy of my one and only scientific paper,” he says.

Harding’s tale begins with a mathematically minded boy, who became interested in investing while helping his civil servant father manage a modest share portfolio. Today, he is based at Winton Capital’s headquarters in Hammersmith — well west of the districts favoured by London’s financial community. On the approach from the Tube station, the long, low-rise building, originally constructed in the mid-20th century, looks underwhelming. A queue of people stretches outside the Job Centre that occupies the first section of the shared block.

Once through Winton’s doors, however, the ground floor opens up into a spacious waiting area, its curvaceous reception desk illuminated with recessed red lights. Much of the art on display has a scientific theme, including a series of large Raoul Dufy prints from 1937, celebrating science and technology.

Harding’s career is founded on the relentless pursuit of mathematical and scientific methods to predict movements in markets. This is a never-ending process because predictive tools lose their power as markets change; new ones are always needed. “We have 450 people in the company, of whom 250 are involved in research, data collection or technology,” he says. That is equivalent to a medium-sized university physics department.

After graduating, Harding began work as a financial trader. Over five years he began to see potential profit in adopting a more mathematical approach — and, in 1987, he co-founded AHL as a commodities trading firm with two other young physicists, Michael Adam and Martin Lueck. Their success, using quantitative methods, led to AHL’s purchase by Man Group in 1994. Harding struck out on his own in 1997, setting up Winton (he gave the company his middle name) with the aim of building a more substantial investment business on the back of empirical scientific research.

In his 1994 paper, Harding wrote that the methods with which conventional banks and brokers make money from trading have “all the intellectual purity of selling vegetables”, a phrase he uses again during our interview. As well as taking clients’ fees, these methods consist essentially of selling complex derivatives at marked-up prices and of arbitrage (taking advantage of small differences in the price of financial instruments on different markets).

Harding has a different approach. He exploits failures in efficient market theory — “the idea that markets are always rational, that they perfectly reflect all knowable information and always produce in some sense the ‘right’ price”. This theory still has a grip on western economic thinking, he says, despite much evidence that it is wrong. “It treats economics like a physical science when, in fact, it is a human or social science. Humans are prone to unpredictable behaviour, to overreaction or slumbering inaction, to mania and panic.”

The Winton investment system is based instead on “the belief that scientific methods provide a good means of extracting meaning from noisy market data. We don’t make assumptions about how markets should work, rather we use advanced statistical techniques to seek patterns in huge data sets and base all our investment strategies on the analysis of empirical evidence. We conduct our research in the manner of a science experiment — collecting and organising data, making observations and developing hypotheses and then testing these hypotheses against empirical evidence.”

Harding emphasises the breadth and volume of investments involved, covering bonds, currencies, commodities, market indices and individual equities. The aim is to exploit a large number of weak predictive signals, he says: “We don’t expect to find any strong relationships between data and the price of the market. That may sound counter-intuitive but if there are strong relationships, someone else is going to be exploiting those. Weak relationships are where we have a competitive advantage.”...MUCH MORE

No kidding.

Compare the paragraph immediately above with this from Nov. 21's "Inside Renaissance Technologies' Medallion Fund: A Moneymaking Machine Like No Other (and President-elect Trump's Sharpe ratio)";

...At the 2013 conference, Brown referenced an example they once shared with outside Medallion investors: By studying cloud cover data, they found a correlation between sunny days and rising markets from New York to Tokyo. “It turns out that when it’s cloudy in Paris, the French market is less likely to go up than when it’s sunny in Paris,” he said. It wasn’t a big moneymaker, though, because it was true only slightly more than 50 percent of the time. Brown continued: “The point is that, if there were signals that made a lot of sense that were very strong, they would have long ago been traded out. ... What we do is look for lots and lots, and we have, I don’t know, like 90 Ph.D.s in math and physics, who just sit there looking for these signals all day long. We have 10,000 processors in there that are constantly grinding away looking for signals.”...Brown is Peter Brown, Co-Chief Executive Officer of RenTech.

I'd say Cookson got the money quote, so to speak.