From Alhambra Investments:

Though I highly doubt he will admit it, he’s just not the type, even Ben Bernanke knows on some level that bond market is decidedly against him, or at least his legacy. Economists have a funny way of looking at bonds, decomposing interest rates into Fisherian strata. To monetary policy, interest rates break down into three parts: expected inflation over the term of the security; the expected path of real short-term rates; and the residual term premium. Policymakers love to focus on the last one even as (or especially because) it is the most esoteric.

To gain monetary “stimulus”, officials believe that they must arrest and reduce term premiums. What is a “term premium?” It is what economists believe is the extra return a bondholder demands in order to hold a longer range fixed income instrument. In other words, all else being equal (as economists like to surmise) where the path of real short-term rates is the same as are inflation expectations, the term premium determines where an investor will buy a bond in maturity versus something shorter or longer. Economists like Bernanke argue that term premiums are high where risk is perceived to be high; in other words, you have to be compensated that much more for holding a bond for that much longer.

From that perspective, term premiums make sense in a monetary policy setting, as does the surface considerations for QE. If QE can affect long-term rates while holding the others equal or better, that suggests lower risk of investing overall.

The trouble for policymakers is that on this side of the Great “Recession” we don’t even need to account for the academic posturing. On March 20, 2006, new Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke discussed the unusual nature of low interest rates of that time. Alan Greenspan had left Bernanke his “conundrum” where he raised short-term rates considerably (in his view) but longer rates failed very conspicuously to follow. In a speech to the Economic Club of New York, Bernanke noted this disparity:

For example, since June 2004, the one-year forward rate for the period two to three years in the future has risen almost 1-1/2 percentage points. As the ten-year yield is about unchanged even as its near-term components have risen appreciably, it follows as a matter of arithmetic that its components representing returns that are more distant in time must have fallen. In fact, the one-year forward rate nine years ahead has declined 1-1/2 percentage points over this tightening cycle.The question was about how to interpret the apparent inconsistency. To Bernanke, it was a matter of breaking down the constituent parts of rates:

To the extent that the decline in forward rates can be traced to a decline in the term premium, perhaps for one or more of the reasons I have just suggested, the effect is financially stimulative and argues for greater monetary policy restraint, all else being equal. Specifically, if spending depends on long-term interest rates, special factors that lower the spread between short-term and long-term rates will stimulate aggregate demand. Thus, when the term premium declines, a higher short-term rate is required to obtain the long-term rate and the overall mix of financial conditions consistent with maximum sustainable employment and stable prices.This was not the only possibility (and again there are serious doubts as to just how realistic this view actually is). Juxtaposing that more hopeful condition against another scenario, Bernanke gives us his own answer to the current predicament delivered long before its appearance.

However, if the behavior of long-term yields reflects current or prospective economic conditions, the implications for policy may be quite different–indeed, quite the opposite. The simplest case in point is when low or falling long-term yields reflect investor expectations of future economic weakness. Suppose, for example, that investors expect economic activity to slow at some point in the future. If investors expect that weakness to require policy easing in the medium term, they will mark down their projected path of future spot interest rates, lowering far-forward rates and causing the yield curve to flatten or even to invert.In terms of Fisherian decomposition of longer term interest rates, this means that where the expected path of short run real rates is low and gets lower then reduction in long-term rates is not helpful via lower term premiums but increased (perceived) risk accompanying that mark down. Typically we see this behavior where the UST curve inverts, but that is not the only way to observe it; and I would argue, given the state of short end activity, it is not the correct way.

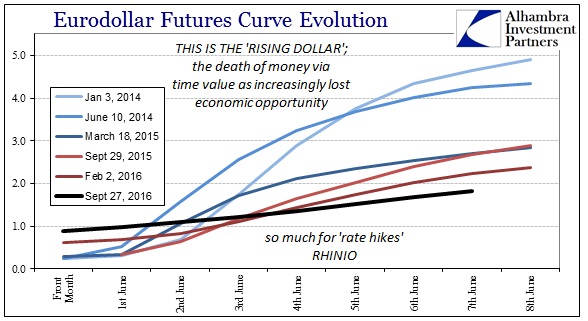

In fact, there is an alternate method to derive what might be the expected path of short run rates, real or otherwise – the eurodollar futures curve. In the last nearly three years of this “rising dollar” and its preceding months, the eurodollar curve has not just flattened but done so in remarkable fashion. What it suggests about both the time value of money and overall risk/opportunity is nothing short of alarming. It qualifies in every way for Bernanke’s definition of “if investors expect that weakness to require policy easing in the medium term, they will mark down their projected path of future spot interest rates.” In the case of eurodollar futures, though they are not connected to spot rates but 3-month LIBOR, it is perhaps a more appropriate substitute (we could also use the OIS curve, as its history accomplishes the same result).

What was once a curve is now not. It has become a straight line that serves as a reminder of the death of money and time value, two key components that more than suggest risks and (lack of) opportunity. The yield curve doesn’t invert because current short rates are already near zero, so the decomposition of far forward expectations of spot rates indicates a huge increase in risk perceptions. From that view, falling longer-term rates simply confirm the worst regardless of inversion....MUCH MORE