In 2015's "The Long-Term Oil Play" I noted, off-the-cuff, some of the things that we think about:

Some of the easily identifiable considerations to plug into your model are the depressive effects of slowing population growth and international agreements to use force to further the stranded assets argument, the inflationary effects of a reduction in the total resource and more particularly in the lower cost plays and the could-go-either-way interplay of price and regulation in the development of alternative transportation and whether Saudi Arabia asks Pakistan to lend them 60-70 nukes until their domestic nuclear development program gets going.Al Gore tried to frame it as analogous to the sub-prime bubble but no one is really listening to him anymore.

Then there are the unknown unknowns....

Right now we give more weight to electric vehicles displacing some percentage of internal combustion engines as a driver of oil prices, rather than the political keep-it-in-the-ground stuff, but don't think either will be a big factor over five years.

(despite Nissan's forecast that 20% of year 2020 car sales in Europe will be electric)

There are some folks who say the Saudis started the 2014 price war because they know the UN (or some international body) won't allow them to pump after, say, 2025 and the Kingdom decided it's better to get something for the goo right now than nothing down the road.

That story ignores the fact that the highest value for oil in the long run is probably as petrochemical feedstock where it doesn't get burned at all.

So who knows.

Here are some more considerations from David Keohane at FT Alphaville:

Saudi Aramco, a race to the bottom?

It’s a theory at least, courtesy of a new Bernstein long read on the reported listing of 5 per cent of the state owned oil and gas giant by 2018.

The final highlighted bit being the point, with the question being “why now?”:Apart from that, here’s a comparison, income and valuation table from the note to keep you going:...

Often the simplest explanation is the most likely to be correct. With Saudi running a significant budget deficit, the listing of Aramco is one way to plug a gap in government finances. More broadly the listing of Aramco could be an example to other state owned firms, as Saudi reaches its ‘Thatcher’ moment in seeking to privatize state owned companies to increase efficiency as part of their plan to move beyond oil. The problem for oil markets is that privatized state companies tend to grow more quickly following privatization. Perhaps Aramco’s growth will be focused on refining and natural gas, but it is possible that Saudi have also realized that demand is likely to run out before supply and it makes more sense to deplete their own reserves ahead of others. While this is pure conjecture at this point, it could have bearish implications for oil markets. In the near term however, Saudi will not want to list Aramco at a low oil price. In the run up to 2018, we expect that Saudi will do everything in its power to ensure oil markets remain balanced and prices stable. This could be positive near term for oil equities.If that last theory is correct, it’s a solid end of the oil age gambit that is based in part on an eventual race to produce kicking in.

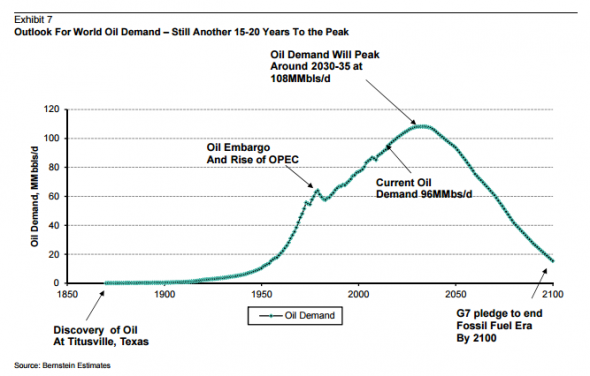

Venezuela is another that might want to start mulling such an outcome, even if, as Bernstein suggest, Occam’s razor points to a budgetary hole that needs filling as the probable reason for the planned listing. Still, assumption heavy as it is, this kind of chart is worth keeping in mind:

...MORE