A major piece from Bloomberg:

Theranos wants to convince the world it’s for real.

Elizabeth Holmes rarely slips out of character. When she responds to questions in an interview or on a conference stage, she leans forward, leg crossed ankle over knee in a half-lotus manspread power pose. She lowers her voice an octave or two, as if she’s plumbing the depths of the human vocal cord. Although she hates it being remarked upon, her clothing, a disciplined all-black ensemble of flat shoes, slacks, turtleneck, and blazer buttoned at the waist, is impossible not to notice. She adopted this uniform, as she calls it, in 2003, when she founded Theranos, a company seeking to revolutionize the medical diagnostics industry by doing tests using only a few drops of blood.See also our June 13 post "Theranos: She's Young, She's Rich, Is She A Marketing Huckster?".

“I wanted the focus to be on my work,” she says slowly and deliberately. “I don’t want to go into a meeting and have people looking at what I’m wearing. I want them listening to what I’m saying. And I want them to be looking at what we do.” She pauses, then adds, “Because when you walk into the room and you’re a 19-year-old girl, people interact with you in a certain way.”

All the same, Holmes says, she wasn’t prepared for how eager people would be to tear her down. “Until what happened in the last four weeks, I didn’t understand what it means to be a woman in this space,” she says, shaking her head. “Every article starting with, ‘A young woman.’ Right? Someone came up to me the other day, and they were like, ‘I have never read an article about Mark Zuckerberg that starts with ‘A young man.’ ”

Holmes, now 31, is sitting in her office. The surfaces are curved and gleaming, and the giant, orblike light fixtures seem to have been taken from the Starship Enterprise as reimagined by Jean Nouvel. The windows offer panoramic views of the flora of Palo Alto, where Holmes has become one of the most obsessed-over entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley. Partly this is a result of her ambition to make getting a blood test as fast and as simple as checking your bank account balance. If Theranos succeeds, Holmes says, anyone, anywhere, could have access to information about their health and risk of disease anytime they want, without a prescription. Theranos does that, she says, with as little as a finger prick’s worth of blood, a much smaller amount than traditional blood tests, and at a fraction of the cost. Theranos charges from $2.67 for a glucose test to $59.95 for a range of sexually transmitted diseases and posts all of its prices online, a level of transparency no traditional lab company matches. Holmes says her company can conduct reliable testing for 50 percent to 80 percent less than Medicare reimbursement rates, which could lead to astonishing cost savings. She estimates that $2.2 billion would be saved each year in Arizona alone, where the company has a presence in 40 Walgreens pharmacies.

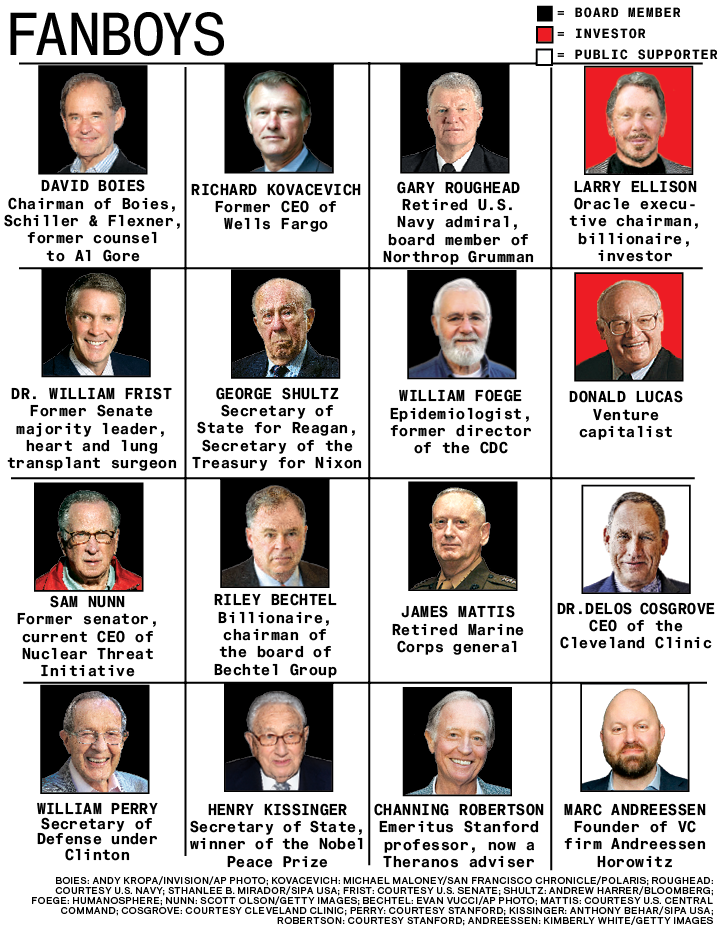

The Theranos story has also been amplified by its $9 billion valuation, based on its venture capital funding, as well as by the roster of powerful board members (Henry Kissinger, William Perry) and public supporters (Marc Andreessen, among others) Holmes has gathered around her. But Holmes herself is as much a source of fascination as her company. She has just the right mixture of boldness and precocity that Silicon Valley loves. She was only too willing to let that propel her through the business media’s star chamber, though she refused to let photographers use a wind machine to blow her hair.

On a typical day, Holmes would be overseeing Theranos’s 1,000 or so employees, but on this afternoon in late November she’s under siege. In her office, she’s joined by Theranos’s general counsel and a newly retained public-relations crisis expert who monitors every tic and utterance. An aide silently enters the room and hands Holmes a cup of green liquid, which contains coconut water and kale, along with other organic extractions. Stacks of paperwork, test data, and U.S. Food and Drug Administration applications sit on the table in front of her, all intended to prove that Theranos’s products work as she says they do.

After several years of Holmes telling the largely unchallenged story of how Theranos intends to change the world, a blast of cold air came on Oct. 15, when the Wall Street Journal published the result of a five-month investigation by John Carreyrou. The piece reported that as of the end of 2014, Theranos wasn’t using its own products and technology to analyze most of the tests it was conducting for consumers. Former employees, the article further reported, claimed Theranos was cheating on routine proficiency tests, which help federal regulators determine if a particular lab is producing accurate results. The implication was that Theranos’s technology was largely a charade. A series of similarly critical articles followed. Bloomberg News reported that some Theranos partners that had signed deals with the company, including AmeriHealth Caritas and Intermountain Healthcare, hadn’t actually started using the technology yet. The bright-eyed woman the media had clambered over themselves to mythologize was now being picked apart.

On its website, Theranos denied the accusations, then went about trying to find people who could come to its defense. “Here’s what happens every time I have a huge winner,” says Tim Draper, founding partner of venture capital firm DFJ and a Holmes loyalist whose $1 million investment made Theranos’s incubation possible. “The first thing that happens is that the competition sort of pooh-poohs it. Then the next thing that happens is they go, ‘Uh-oh, this is threatening our business.’ … She’s opened the kimono, and it’s scaring the pants off the competition.”...MORE

And 2014's "Why Are So Many Political Heavyweights On the Board of Theranos?"

Old guys seem to like her: